Back

In

Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood, which long served

as Fred Rogers’ creative base, another far-reaching

educational effort involving cameras and television screens

is well underway. Because the Pittsburgh region stands

to benefit whenever a homegrown product aims for a national

market, this small but expanding enterprise merits some

notice.

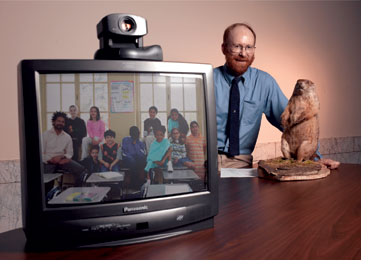

On more than 70 occasions during the past year,

staff at Carnegie Museum of Natural History have conducted

videoconferences

with elementary, middle school, and high school audiences

from New York to Texas. We market these class-length programs

to schools via electronic bulletin boards, and topics for

our classes range from moth anatomy

to dinosaurs.

As a member of the small team responsible

for the development and delivery of these new programs,

I quickly learned that,

except for the half-second delay in voice transmission,

the experience of facing a camera mounted just above the

televised image of students who are watching your televised

image on their TV monitors is pretty comparable to being

a guest instructor in a classroom. In both situations,

teaching strategies must be carefully planned

in advance and, depending on student interest, knowledge,

and behavior, they sometimes have to be drastically altered

at a moment’s notice.

A few times during these sessions,

when audio and visual connections were established several

minutes before the

formal distance learning sessions began, we had the advantage

of hearing candid student exchanges that we thought gave

us clues about our audience’s attitudes and capacity

to learn. “Did you come up with some questions like

we were supposed to?” one sixth-grader asked her

companion one late January morning as the girls entered

their classroom and unknowingly passed close by the camera

linking their Oyster Bay, Long Island classroom to equipment

some 330 miles to the west. “No,” I heard the

second student reply as I readied materials in the museum’s

first floor studio, “I thought I’d just make

something up during class.”

Forty minutes later,

during the conclusion of a session about the real creature

behind Groundhog Day folklore,

the young procrastinator posed a question that left me

admiring her intellect while stammering for some I’m-going-to-have-to-get-back-to-your-teacher-about-that

cover. “You showed us a lot of stuff about groundhog

adaptations,” she began, directing her question to

me via the camera, “but how did hibernation evolve

as a mammal behavior?”

On another occasion, when the

audio and video link wasn’t

established until exactly the time the videoconference

session was scheduled to begin, the image that flickered

onto the museum’s monitor was disarming enough to

break all my concentration. Normally, we devote the first

minute of every session to explaining how patience is required

in order to deal with the half-second sound delay in video

transmission. But on this late October afternoon, when

a second grade class from an Ann Arbor, Michigan school

suddenly appeared on the monitor wearing the hand-colored

bat masks they’d assembled in a preparatory lesson,

all I could think to say was, “Wow. You all look

so cute!”

Like many other innovative ventures in the

nonprofit sector of western Pennsylvania, the museum’s

distance learning program owes its start to a local funding

institution.

A generous grant from The Grable Foundation has covered

the cost of equipment, staff time, and the use of specialized

phone lines capable of achieving the two-way digital transmission

of image and sound.

But in spirit, at least, I can’t

help but feel that such remotely televised educational

programming also owes

a debt to another Pittsburgh institution—Fred

Rogers.

During the clean up after one videoconference with

a third-grade class in Plano, Texas, a colleague who handles

the program’s

technical side shared an observation: “I don’t

know whether you were aware of it, but when you made the

unpacking of the bat skulls part of the program, you kind

of had a ‘Mister Rogers thing’ going on.”

I

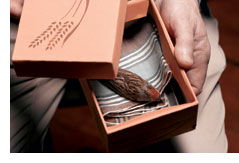

confessed to awareness, even premeditation. As proof, I

retrieved a personal reminder of the great man’s

work from a nearby table. Under the lid of a small decorative

cardboard box, the preserved remains of a chipping sparrow

rested upon a folded handkerchief. Many years ago, a representative

of Family Communications, the production

company of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, borrowed

the sparrow remains from the museum’s loan program

to play the part of a dead bird in an episode whose story

line explained death as a natural part of life.

I keep that

sparrow nearby anytime my duty as a museum educator requires

me to face a camera to reach a student

audience. The lifeless specimen serves as a physical

link to the pioneer who long ago proved that the quality

products

Pittsburgh sends out to the world do not necessarily

have to leave town via trucks, barges, or on the backs

of railcars. I keep that

sparrow nearby anytime my duty as a museum educator requires

me to face a camera to reach a student

audience. The lifeless specimen serves as a physical

link to the pioneer who long ago proved that the quality

products

Pittsburgh sends out to the world do not necessarily

have to leave town via trucks, barges, or on the backs

of railcars.

Above right: The preserved sparrow

that Fred Rogers borrowed and then returned wrapped in

a new

handkerchief

and decorative box

still inspires Pat McShea today.

Since

its inception in 2002, Carnegie Museum of Natural

History’s

Distance Learning Program, made possible through a grant

from The

Grable Foundation,

has reached

more than 2,000 students and teachers as far

away as Arlington, Texas. A recent grant from the

Claude Worthington

Benedum

Foundation will support future videoconferences

in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

Back

| Top |