|

||||||||||||||||

Six of the 11 photographers will come together for a panel discussion at the museum on September 22. They are: Erika Larsen, Kitra Cahana, Jodi Cobb, Amy Toensing, Carolyn Drake, Beverly Joubert, Stephanie Sinclair, Diane Cook, Lynn Johnson, Maggie Steber, and Lynsey Addario. |

A Woman's World

Female photographers on assignment for National Geographic are a visual force, connecting the world to some of the most powerful narratives of the last decade, often with stories only they can tell. Like slices of meat from the deli counter, cross sections of a pair of brains are placed on a table in a University of California, Los Angeles, medical facility. It’s just what Maggie Steber ordered. On assignment for National Geographic, the photographer’s task was to document the science of recall and the tragedy of memory loss. A sidebar to the story included a collage of images of her mother and only parent, Madje Steber, who ultimately died from Alzheimer’s disease, along with intimate portraits of others suffering from vanishing memories.

Steber spent nearly an entire day photographing those “memory boxes,” as she calls them. She built a small set and methodically experimented with the lighting. In the end, she created a simple yet startling image showing the disease-free specimen with its temporal lobes intact next to a diseaseriddled brain with gaping holes where the lobes once existed. “Now you can understand what happens with Alzheimer’s,” says Steber. Providing that visual clarity, a gateway to better understanding both our interior and exterior worlds, is perhaps what best defines National Geographic. It should come as no surprise then that in 2013, when the National Geographic Society was preparing to celebrate 125 years, the powers that be—in this case Kathryn Keane, vice president of exhibitions at the National Geographic Museum, and Elizabeth Cheng Krist, senior photo editor at the magazine—decided to create a traveling photography exhibit. In an effort to narrow the focus, they established a few guidelines, most notably to concentrate on the first decade of this new millennium. After reviewing thousands of images, Keane and Krist realized that many of the most moving images just happened to be created by women. More specifically, 11 women. In addition to Steber, the list includes Lynsey Addario, Kitra Cahana, Jodi Cobb, Diane Cook, Carolyn Drake, Lynn Johnson, Beverly Joubert, Erika Larsen, Stephanie Sinclair, and Amy Toensing. “Some felt that being a woman was an advantage, while some felt it made them more vulnerable. The truth is they are all very brave.”

- ELIZABETH CHENG KRIST, CURATOR, WOMEN OF VISIONAnd so, Women of Vision: National Geographic Photographers on Assignment was born. After touring the country for three years, the show will make its final stop at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, September 22, 2016, through January 8, 2017. “I don’t usually notice if an image is shot by a man or a woman,” says Krist, who worked at National Geographic for 21 years and edited some four million images. In fact, the general consensus is that the pictures themselves—the composition and lighting—do not betray the gender of the shooter. However, gender may impact how a photographer is perceived in different parts of the world and how she perceives the world around her.

“Some felt that being a woman was an advantage, while some felt it made them more vulnerable,” says Krist, who also served as the show’s curator. “The truth is they are all very brave.” ODD WOMAN OUTFor Jodi Cobb, her credentials as a woman ultimately helped shape some of her most acclaimed work. But throughout her career, including her stint as a National Geographic staff photographer—notably, one of only four in the magazine’s history—she was always the odd woman out. “I found myself doing all these ridiculous, macho things,” says Cobb, who was among the first female photographers almost everywhere she worked early in her career, including National Geographic. “Then came the Saudi Arabia story.”

This 1987 assignment called for her to document the seemingly opaque lives of Saudi Arabian women. Cobb was able to gain unprecedented access no man would ever be granted. The results were a revelation, both in terms of the images she brought home and the new-found freedom she took with her. “That’s when I discovered I love these kind of stories about women’s issues,” she says. “This is my niche.”

Cobb has since held up a light to other veiled institutions, including the 21st-century enslavement of women in diamond mines, factories, tomato fields, brothels, and brickyards around the world. She was also the first photographer granted unprecedented access to the beautiful, and sometimes tragic, lives of the Japanese geisha community. One of her images featured in Women of Vision depicts women in Chennai, India, laboring to pay off loans that in reality will be passed on to their daughters and granddaughters. “The ‘brick lady’ is one of the photographs that means the most to me,” Cobb says. “You can see the weight of the bricks on her head and the stoicism in her face.” Access is one thing, making sure you blend into the scenery, especially when carrying a camera, is another. “Of course, just being an American I stick out like a sore thumb,” notes Amy Toensing.

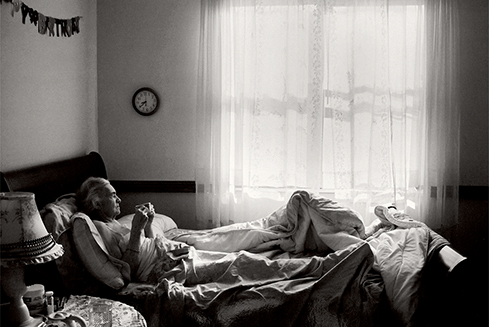

As an American woman and a photographer, she brings new meaning to the phrase dressing for success. “I have to make sure I’m respectful in what I’m wearing. Being a photographer is really physical, so I spend a lot of time thinking about how to dress,” Toensing explains. “Packing is very stressful.” But once those bags are packed, she’s able to truly immerse herself in new places—a village in Egypt, the jam-packed Jersey Shore, an Aboriginal camp in Australia—and learn something about the people who live there. “It’s a dance,” she says, “and we both have to show up. I need my subjects to be a part of it, but I also have to get out of their way.” In her image of colorful dresses hanging on a clothesline in the mountains of central Puerto Rico, Toensing presents a puzzle of sorts. Just where are the little girls to whom these dresses belong? “When you leave something out,” she says, “it allows the viewer to imagine and make connections. It’s more intimate.” AGENTS OF CHANGEIntimate also describes Steber’s work. “Even in terrible situations,” she says, “we find tender moments.” For the past 30 years, she has covered Haiti during times of conflict, disaster, and grace. She has feared for her own life and celebrated the lives of others. “In the midst of all this chaos and hell on earth,” Steber says, “I can suddenly see a little girl with a new red ribbon in her hair. I can see hope. “The Haitians are so brave,” she adds. “They have taught me how to be brave.” It’s a lesson that helped her navigate her own perilous journey—her mother’s battle with Alzheimer’s disease. At first, Steber took photos of her mother just for herself, to create new memories. Then came her assignment from National Geographic. The brain image selected for Women of Vision is different from the one that appeared in the science of memory story in the magazine. “We use photography to illuminate our world, and that can lead to changing it.”

- LYNN JOHNSON“When the doctor came in to collect the brain slices, I thought, ‘Now, this looks dark and Hannibal Lecter-like,’” Steber recalls. In that moment, she decided to incorporate the doctor’s hands, sheathed in bright-blue latex gloves, so the image “became less about the brain and more about the mystery.” While working on this story, Steber found herself confronting the biggest mystery of all. “You can run from this end-of-life experience or you can face it and be a warrior,” she says. “The photographs helped me become a warrior in my mother’s death.”

“A photograph can impact someone on a very deep level and move them to action,” says photographer Lynn Johnson, who lives in Pittsburgh. “I do feel the weight of that; it’s not overwhelming but it does feel important.” So important that sometimes she prefers to picture the world in stark black and white. “National Geographic doesn’t want you to shoot in black and white,” the former Pittsburgh Press photographer says, “but I’ve proposed it as an aesthetic solution.”

In her image, Conversation and Culture, she paints a joyful yet muted scene of customers gathered in a beauty shop, one of the few woman-owned businesses in Zambia. “With black and white images,” Johnson says, “you look at the content rather than the postcard color or the home décor elements. It’s all about the substance, the moment, the light— the content.” The search for that content is not for the faint of heart. Johnson and her camera have been unflinching in the presence of disease (monkeypox victims in parts of Africa), devastating injuries (children wounded by land mines in Cambodia), and despair (women who were sexually assaulted while serving in the United States military and are now suffering from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder). Lynsey Addario, a seasoned conflict photojournalist with more than a decade of experience in the Middle East, has been kidnapped twice. First in 2004 and again in 2011, when she was one of four journalists from The New York Times held hostage in Libya by pro-Qaddafi forces. When asked why she first chose to cover war, Addario told NPR, “I was interested in how women were living under the Taliban, for example. So it was really the story that brought me to these places, and if they happen to be in a war zone then so be it. Or if injustices against women or hardships were a byproduct of war—or many years of war— then that’s what I was interested in covering. … And at some point, people started calling me a war photographer. And it was very confusing to me because I actually didn’t ever think of myself as that.” It’s a deep commitment to storytelling, says Johnson. “We all work on complex stories in volatile situations. Each of us is so committed,” she says. “That’s our common bond.” Another bond that unites these storytellers: their fundamental belief that by putting the world’s humanity (and inhumanity) on display, something might happen. Something good. Maybe a conversation. An outcry. A change. “We use photography to illuminate our world,” Johnson says, “and that can lead to changing it.” The exhibition’s 100-plus images will be arranged so that each photographer has her own gallery. This approach, Cobb says, allows visitors to “see the totality of the vision of the photographer, to see how her style and aesthetic vision work together.” Still, each photograph must also be able to stand on its own. “We wanted every single image to be informational and incredibly visually striking,” Krist says. “We had the luxury of picking only the best.” And because the prints are so large, Steber says, “You meld or melt into them; it’s a richer experience than looking at them in the magazine.” “It increases the power of the experience,” adds Johnson. “It’s a portal or invitation into a different way of thinking and seeing.” That invitation is far ranging—from cityscapes, a Sami village in Sweden, and Texas teenagers to leopards in the wilds of Africa, the plight of child brides, and the resurgence of Shamanism. Often it reflects years dedicated to a single place or topic. What you will see are 11 distinct points of view. “There is an incredible breath of vision,” Toensing says. “It’s a broad brush in terms of style and subjects,” Steber says. “We are all women, but we are dramatically different individuals,” Cobb notes. The exhibition makes clear there is no ubiquitous definition of a woman photographer. But if it had an overarching goal, it could be to set the next generation of photographers in motion. “I hope people realize how photography can elevate our understanding and emotional intelligence,” Krist says. “I would love to think that someone could come to the show and feel inspired.” Women of Vision is organized and traveled by the National Geographic Society. The PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. (NYSE: PNC) is the Presenting National Tour Sponsor for Women of Vision.

|

|||||||||||||||

Organizing Delirium · My Perfect, Imperfect Body · Body Boundaries · LIGHTIME · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Laura Micco · Artistic License: Making Some Noise · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |