Fall 2016

Fall 2016|

Making Some Noise

A yearlong public art project on the North Shore invites three Pittsburgh-based artist-activists to speak their minds through their art. Sitting inside print studio Artists Image Resource (AIR) on the North Side, artist and hip-hop historian Paradise Gray searches through photographs on his laptop. A natural storyteller, he pulls up an image and instinctively asks, “What do you see?”

In the foreground of the photograph is a park with two public play areas separated by a fence. A school sits in the background. To the right of the fence, the lawn is manicured. To the left are towering weeds. At Gray’s prompting, a closer look reveals the area on the right is a baseball field, and on the left, an overgrown and crumbling cement court with a rusted basketball hoop—minus the net, rim, and backboard. “Who is most likely to play here? Black kids,” the artist says, pointing to the remnants of the basketball court. “The perfectly manicured lawn demonstrates the argument for America’s Most Livable City. When Pittsburgh was named Most Livable City, [fellow activistartist] Jasiri X and I raised the question: For who? For African-Americans in Pittsburgh, this is our reality.” “As artists, I believe it’s our responsibility to be translators between cultures, between histories, between people.”

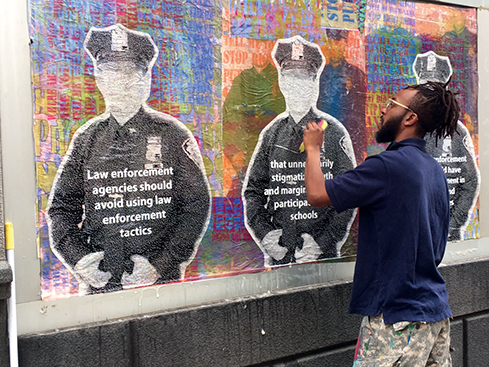

- D.S. KINSEL, ARTIST AND CO-FOUNDER OF BOOM CONCEPTSThe city park in the photograph is adjacent to Pittsburgh King, a Pittsburgh Public School on the North Side attended by Gray’s grandchildren. “Let me show you how Pittsburgh fixed the problem,” he continues, flipping to a second image in silence. In it, the weeds, cement, and pole are gone, perfectly manicured grass in its place. This pair of images is part of a series Gray calls Disappearing Blackness in Pittsburgh, his contribution to the yearlong public art project Activist Print. A collaboration between The Andy Warhol Museum, the creative hub BOOM Concepts in East Liberty, and AIR, Activist Print is inspired by generations of artists using silkscreen and print-based media to raise awareness of social justice issues. A successful Kickstarter campaign, in partnership with Art Basel’s Crowdfunding Initiative, made it possible to commission work by three Pittsburgh-based, communityminded artists with diverse voices, including Gray, who moved to the city from the Bronx in 1992. Their blank slate: the windows of the vacant Rosa Villa building across the street from The Warhol, at one of the North Shore’s most travelled intersections. Joining Gray in “making some noise,” as he calls it, are artists Bekezela Mguni and Alisha B. Wormsley. “We wanted to make sure people who are already doing social justice work in the community had the opportunity to use AIR as a resource, to build a relationship with The Warhol, to build their portfolio with a sanctioned piece of public art, and at the same time be paid a stipend for their work,” says BOOM Concepts co-founder and project leader D.S. Kinsel. To launch the project in May, Kinsel installed his own work, What They Say, What They Said, which highlights responses by African-American men living in Pittsburgh’s East End to the prompt,“What do the police say when they see you?” The foreground features police silhouettes containing excerpts from President Obama’s “Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing.” At Kinsel’s invitation, Pittsburgh Police Chief Cameron McLay and Pittsburgh Police Commander Eric Holmes attended a public talk at The Warhol centered on community and policing. “As artists, I believe it’s our responsibility to be translators between cultures, between histories, between people,” says Kinsel. Fresh from her first summer as an MFA candidate at the prestigious Bard College in New York, Wormsley isn’t quite sure yet what she’ll wheat paste onto the Rosa Villa windows this fall; she plans to use “new juice” from her time at Bard to create something fresh. “Whatever I do, it’s not that I’m going to focus on social justice, but because I’m a member of two oppressed groups in this country, whatever I create is going to be something that is going to expand the possibilities of those oppressions,” says Wormsley, who is African-American.The interdisciplinary artist helps empower students at Westinghouse Academy as the creative director at the Homewood Artist Residency, both a community and in-school arts program initiated by The Warhol in 2010. Her work there inspired her series There are Black People in the Future, which consists of found items from Homewood onto which she printed the statement. “I like to work from the empowered place, so if I say there are black people in the future, then there are black people in the future, period,” says Wormsley. “I always write it in caps. It’s not even an affirmation, it’s a fact.” Wormsley, whose practice considers collective memory across time, is a science fiction fan. As a genre, she notes, it includes a somewhat diverse representation of people, unlike Hollywood. In making There are Black People in the Future, she considered that fact alongside the current social climate in the United States. “I was thinking about how, through the media, you can really feel that there are institutional forces working against the future of African-Americans in this country,” she says. Bekezela Mguni’s work also comes from a place of empowerment, catalyzed by those who came before her, including agitators and visionaries Gray, Wormsley, and Kinsel. But especially Audre Lorde, an iconic black, feminist, lesbian theorist and poet. Lorde inspired Mguni’s traveling pop-up installation and intervention, the Black Unicorn Project, which includes more than 400 books by black women and queer and trans people of color, all borrowed and sponsored by Carnegie Libraries. “People think of a librarian as a passive or neutral position,” she says. “But I’m a radical librarian. I believe librarians have a social responsibility to the communities they serve.” Mguni grew up in Trinidad, an avid reader who regularly visited a Carnegie Library. “One of the greatest pleasures in the world is when you find a story you really connect with,” she says. “Storytelling can change people’s lives. There’s that potential of stepping into another person’s life and developing empathy. Black women writing about their lives saved so many lives; it’s about seeing that there is a reflection of you in the world.” And it’s more important than ever, the artist says. During a recent Black Lives Matter Day of Action in Pittsburgh, Mguni read aloud the names of African-Americans killed this year by police. “It took a full six minutes,” she says. “Think about someone you love and how you feel when they’re taken from you. That’s how we feel; we’re mourning. People don’t realize the amount of grief black people live with and have lived with. If they did, they would weep. I’m angry that we have to continue to explain it.” Mguni is still considering what she’ll contribute to Activist Print, a project that will expand the audience of all three artists due to its high-traffic location. “I’d love simply to paint something beautiful, but I don’t know that I have that luxury to make art for art’s sake,” she says. “It’s a very important platform and I need to speak what’s in my heart and mind.”

|

Organizing Delirium · My Perfect, Imperfect Body · Body Boundaries · A Woman's World · LIGHTIME · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Laura Micco · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |