|

||||||||||||||||

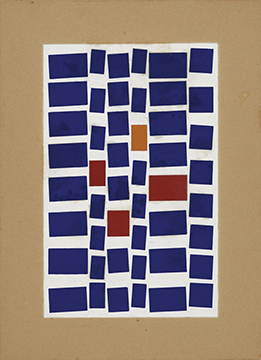

Hélio Oiticica, Filter Project—For Vergara (Projeto Filtro—Para Vergara), 1972, Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro, and Galerie Lelong, New York All artworks by Hélio Oiticica © César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro |

Organizing Delirium

Hélio Oiticica challenged the traditional boundaries of art, and its relationship with life, by turning the viewer into participant. This fall, Carnegie Museum of Art visitors will experience the influential Brazilian artist’s first major U.S. exhibition in more than two decades.

The dancers hailed from the hillside favela known as Mangueira. One of Rio’s urban slums, Mangueira was home to the city’s bestknown samba school, where the dancers had met and become friends. Feelings of classism! racism! drummed through the crowd. The procession had been organized by the exhibiting artist Hélio Oiticica, who promptly turned and led the parade of people wearing or carrying his Parangolés—a series of radical works including capes and banners—around the museum’s gardens instead. The event inspired Oiticica’s rallying cry: “Museum is the world; it is daily experience!”

Just one year before, an oppressive military dictatorship had come to power in Brazil. Along with the country’s avant-garde, Oiticica responded by making vibrant revolutionary art. Then 27 years old, he was not only interested in the political, social, and ethical role of art, but also in collapsing art into life, in creating works that were not only participatory but collaborative, to be completed by the viewer. He wanted his Parangolés to be color-in-motion, symbols of resistance—with inscriptions like “I Embody Revolt” that could be read only when worn and the wearer was in motion. “He was seeking to disrupt the idea of art on a pedestal, both metaphorically and literally,” says Lynn Zelevansky, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, who has spent the last three years immersed in Oiticica’s work.

That will change on October 1, when Carnegie Museum of Art presents Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium, the first comprehensive showing of his work in the United States in more than 20 years and the first ever to travel the country. Co-curated by Zelevansky and partners at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Whitney Museum of Art, To Organize Delirium will debut in Pittsburgh, and will be the first to treat Oiticica’s New York years—where he lived from 1970 to 1978—and his return to Brazil as discrete periods within the trajectory of his career. In his time, Oiticica created wild sensory experiments with a methodical approach that was deepened by time, place, and perspective. English critic Guy Brett described the dual natures that characterize the whole of Oiticica’s life and work as his particular blend of “meticulous order” and “delirious abandon.” To understand his layered process, it’s important, first, to consider its foundation. The Power of the IndividualOiticica was born in 1937 to a family of relative privilege. Home schooled, he drew early influence from two primary figures, his father and grandfather. His father was an experimental photographer as well as an entomologist at the Museu Nacional, the natural history museum in Rio, where he discovered and classified many species of butterflies and moths during his lifetime. As a boy, Oiticica shared a studio with his father and younger brothers. “Attention to structure combined with a wide, free-ranging sense of what the individual can do to invent a world around them were ingrained in Hélio.”

- IRENE SMALL, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF CONTEMPORARY ART AND CRITICISM, PRINCETON UNIVERSITY“In some ways, it was a kind of laboratory that combined conceptual, aesthetic, and scientific experimentation,” says Irene Small, an assistant professor of contemporary art and criticism at Princeton University who has written extensively on Oiticica. In particular, the artist studied the concept of the individual, introduced to him by his grandfather, a renowned anarchist and philologist. He taught Oiticica to consider the individual as the most atomic form of society, embedded in a social context yet also autonomous. “Attention to structure combined with a wide, free-ranging sense of what the individual can do to invent a world around them were ingrained in Hélio,” says Small. On December 10—in conversation with scientists at Carnegie Museum of Natural History—Small will discuss how Oiticica’s father’s study of entomology inspired his own system for naming his works—taxonomic, with series and subseries. The free event is part of the robust public programming around the exhibition, both in and outside the museum. Inaugurating his career, the young artist made a series of works that experimented with color in original and uncompromising ways, a constant throughout his oeuvre.

He began with a collection of paintings, gouache on cardboard, followed by a string of related artistic “propositions.” He created suspended colorful panels to be walked through (Nuclei), painted wooden boxes and glass jars to be manipulated (Bólides), fabric structures to be worn (Parangolés), maze-like spaces to be entered (Penetrables), and, eventually, semi-opaque, semi-translucent compartments to be lived in (Nests). “Once the work leaves the wall and hangs from the ceiling, there’s a kind of interaction with the viewer that will only intensify as his work evolves,” says Zelevansky. To honor this evolution, To Organize Delirium presents these works largely chronologically, both in and around the larger, more expansive installations that marked the latter half of Oiticica’s career. The exhibition opens, fittingly, with a piece that would forecast almost everything Oiticica made after it—Hunting Dogs Project (1961), a never-realized model for a public garden. Labyrinthine, with three entrances and sand covering the ground, it included spaces for group activities like concerts, and inner structures called Penetrables to be discovered alone. One such space designed by poet and critic Ferreira Gullar included a stairwell to an underground room painted entirely in black and empty except for a series of nested cubes— a red cube containing a green cube containing a white cube. The white cube was inscribed with the word “rejuvenate.” “It’s collaboration for the first time,” says Zelevansky. “It’s creation of a public place for the first time. It’s the use of forms like the labyrinth. You see many elements that would stay with him for his entire life in a piece he made when he was 24. That’s certainly unusual.” Collaboration would prove a key concept for Oiticica. He felt art-making and art experience were both to be shared. While Oiticica’s childhood was marked by a rigor that is present throughout his career, Small cautions audiences that “the influence of Hélio’s father and grandfather did not over-determine his practice.” “In fact, when Hélio first goes to the favela Mangueira and discovers samba for himself, one of the famous things he writes is that he had to throw off the excessive intellectualization of his upbringing,” Small says. That was 1964, and it was perhaps his most pivotal year: his father died, the military dictatorship took power, and he first visited Mangueira. Through the window of a city bus, he saw a makeshift structure built with wooden slats, rope, and burlap inscribed with the word Parangolé. The slang term refers to a state of sudden confusion among people. Oiticica became inspired by the margins, where he felt his art also belonged. He began dancing samba. He made friends in Mangueira. And soon he debuted his radical Parangolés, the very works that were cast away from the museum. Collaboration as KeyTo stage a retrospective of Oiticica’s worksin- progress today is to overcome more than one challenge. Works made to be manipulated are now too delicate for handling. Works made for time- and site-specific settings change meaning out of context. And in 2009, many works in Oiticica’s archive were destroyed when a fire tragically ripped through its storage facility in Rio. Knowing all this, in addition to Oiticica’s rejection of the museum as a place for art, one might wonder: Is it even possible to stage a retrospective of his work while staying true to his artistic vision? “It’s a delicate line to walk,” says Zelevansky. “It’s been a great challenge,” says Katherine Brodbeck, associate curator at Carnegie Museum of Art. “It’s not simple to have a straight answer to this question,” says Luciano Figueiredo, a Brazilian artist and former colleague of Oiticica’s. Zelevansky, Brodbeck, and Figueiredo are among a team of experts from inside and outside the museum who have posed and debated the myriad questions necessary to make this exhibition happen. Putting together the first U.S. retrospective since the fire, they have the responsibility of representing “the state of the estate, what is still possible, and how we can move the artist’s work into the future,” says Brodbeck. The exhibition is made possible by three factors. One being the Projeto Hélio Oiticica, a foundation formed by the artist’s brothers after his death, which has done painstaking and delicate work to restore and preserve his legacy. “His brother César told me that after the fire there were shards of glass from the Bólides that were all over the place,” says Zelevansky, “and his brother Claudio sat on the floor and put together every piece.” “What he really wanted to share was the moment of creation. The incredible pleasure and satisfaction of making something, or having an idea that’s really important and figuring out how to follow it through.”

-LYNN ZELEVANSKY, THE HENRY J. HEINZ II DIRECTOR OF CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ARTSecond is the simple fact that “Hélio was an extremely organized artist who kept record of every single piece he produced,” says Figueiredo, who served as the Projeto’s technical director from 1981 to 2008. In keeping with his “orderly” side, Oiticica left careful written instructions on how each work was to be created. He thoughtfully and thoroughly described his intentions in letters to friends. And last, intrinsic to his process all along: his collaborators. The individuals who worked hands-on with Oiticica to create the works can continue to act as contributors. The exhibition team visited Brazil once each year, and sometimes twice, during their three years of research. They met with friends, colleagues, and mentors of Oiticica. They also toured Mangueira and its famous samba school, which still stands, as does Oiticica’s childhood home and studio. “Mangueira was so important to Oiticica, and it was important for us to see it,” says Zelevansky. “It was really interesting to see how they have built it up since Hélio’s time.” She describes a neighborhood with more housing, an athletic center that boasts several Olympic athletes, and a community center detailing the history and founders of the favela’s samba school. In some ways for Zelevansky, the show has been decades in the making. “I’ve been wanting to do a show since I first saw his work in 1989,” she explains. Zelevansky made her first trip to Brazil as a curator for the Museum of Modern Art while scouting under-known living artists to feature as part of their influential Projects series. Oiticica was already deceased, but the team who showed Zelevansky around wanted her to understand the background for the art she was seeing. “They wanted me to understand that the work didn’t come from nowhere. And so they showed me the work of a number of artists, and Oiticica was very prominent among them.” His work took her back to a time when the notion of participatory culture was strong. “Oiticica is absolutely emblematic of that moment in the 1960s,” she says, noting the strong connection to the participatory nature of culture and media today. “I guess there’s nothing new under the sun! But really, the ethos was very close in many ways.” Fostering CreativityTo Organize Delirium has many highlights, including works that reveal Oiticica as a true pioneer of immersive experiences.Tropicália (1966–67), for instance, is his critical portrait of Brazil as a tropical paradise. Inspired by the makeshift structures of Mangueira, the installation includes two Penetrables situated on a field of sand. Visitors are invited to walk among them, tropical plants in pots, and two live parrots inside a cage. (Pittsburgh’s National Aviary will consult on the care of the birds.) Perhaps the most impressive installation, however, is Eden (1969), which Oiticica described as a “campus” and “a kind of mythical place for feelings” and “for constructing one’s interior cosmos.” It marks a break in important ways from his earlier work. When it was originally shown at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, Oiticica collapsed the boundary between the massive installation and past work that was scattered throughout the space, creating new formal and conceptual connections between them.

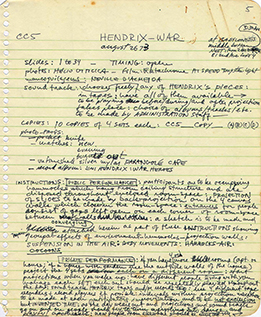

Eden is an example of Oiticica’s personal program for achieving such a state, says Figueiredo. Like Tropicália, the installation consists of Penetrables on a bed of sand, but rather than wedding itself to the visual tradition of Brazil, it remains open-ended. “One [can] go in and feel water, touch leaves, lay down on a bed to just relax,” says Figueiredo. There is a corner filled with hay where you can sit and read newspapers, magazines, and books. “What he really wanted to share was the moment of creation,” says Zelevansky. “The incredible pleasure and satisfaction of making something, or having an idea that’s really important and figuring out how to follow it through.” To experience Eden is not to enter the installation expecting an epiphany or searching for an answer, she says. Rather, it is to allow your subconscious to take over—or perhaps, more simply, to enter and take a nap. To Organize Delirium is set apart, too, by its insistence that Oiticica’s written record does not merely make possible many of his physical works today, but it constitutes a body of work itself. Often considered a “lost decade,” his New York years marked a massive shift in style and form. Having moved to New York in 1970, following several highly successful international exhibitions, Oiticica had expectations of critical success that never quite panned out. Instead he began to experiment with film and photography and to document works that were never made. To critics, because he wasn’t exhibiting, he all but disappeared, but that was a choice. He found himself in the midst of radical social movements still raging in the United States and began to archive his forays into the queer arts communities of New York.

He compiled a massive volume, titled Newyorkaises, written in three languages and a combination of forms like visual poetry, prose, outlines, and footnotes. Pieces of this tome are on display, along with constructed film installations of the period, many of which highlight the artist’s sexuality and drug use. “That book in a sense is the single biggest thing that he creates when he’s in New York, but he never finishes it,” says Zelevansky, “in part because he just loved the idea of something that’s completely open-ended, and always changing.” As the exhibition reveals, for Oiticica, evolution is constant.

Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium is organized by Lynn Zelevansky, The Henry J. Heinz II Director, Carnegie Museum of Art; Elisabeth Sussman, Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography, Whitney Museum of American Art; James Rondeau, President and Eloise W. Martin Director, The Art Institute of Chicago; and Donna De Salvo, Deputy Director for International Initiatives and Senior Curator, Whitney Museum of American Art; with Anna Katherine Brodbeck, Associate Curator, Carnegie Museum of Art. Major support for the exhibition is generously provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Carnegie Museum of Art Fellows, the James H. and Idamae B. Rich Exhibition Endowment Fund, Nancy and Woody Ostrow, the Juliet Lea Hillman Simonds Foundation, the Martin G. McGuinn Art Exhibition Fund, the National Endowment for the Arts, Jana and Bernardo Hees, Anonymous, and Simone and Greg Lignelli.

|

|||||||||||||||

My Perfect, Imperfect Body · Body Boundaries · A Woman's World · LIGHTIME · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Laura Micco · Artistic License: Making Some Noise · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |