|

|||||||||||||||

|

Inside the Cloud Factory

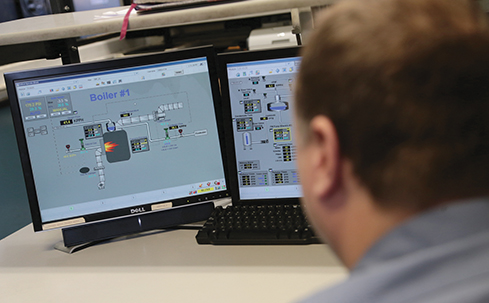

How much of Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood—including Carnegie Museums’ historic building—stays warm. Bob Miller keeps most of Oakland in his pocket. “This is the overview,” he says, as he pulls out his phone and opens a readout identical to the one glowing on his office computer. “It’s telling me: everybody who’s taking the steam, what we’re making, what boiler’s on, and what the temperature is outside.”

Miller is superintendent of Bellefield Boiler Plant, a central steam plant that provides heat and hot water to much of the sprawling Oakland neighborhood, Pittsburgh’s academic hub. Using a smartphone app, Miller can see what’s happening at the facility at any time. It’s some comfort, he says as he slides his phone back inside his shirt pocket, but it doesn’t stop him from worrying. Providing warmth to hospitals and classrooms and maintaining the right humidity to preserve invaluable museum artifacts isn’t a responsibility Miller and his team take lightly. “We help take care of these places,” he says. “The work means something because it benefits people.” Set just back from Boundary Street, the plant is hidden in plain sight, tucked into a small valley between Carnegie Museums’ Oakland facility and Carnegie Mellon University’s ever-expanding campus. Before the plant switched entirely to natural gas in 2009, its original seven boilers demanded a steady diet of coal. Onlookers could stand on Schenley Park Bridge and watch men unload 100-ton cars of Kentucky’s finest from the railroad spur that ran directly into the plant’s yard. Now the only constant reminder of its existence is its famous clouds.

“When it’s very cold out, you see this white cloud [come from the stack],” says Miller, “and that’s the hot gases mixing with the cold air—the ‘Cloud Factory,’ as we’re known.” The whimsical moniker derives from a passage from Michael Chabon’s 1988 book,

“It’s moisture in the gases going out,” says Miller. “It’s not steam, it’s not pollution, it’s water vapor.” Both coal and natural gas are hydrocarbons. Coal has more carbon atoms and therefore creates more carbon dioxide when it breaks down; natural gas has more hydrogen atoms, which forms more water vapor. Which means today’s clouds may be fluffier, more perfectly white and clean, than ever. All in a Day's WorkThe story of how the Bellefield Boiler Plant came to ensure the safety and comfort of those who visit and work in Oakland begins with none other than Andrew Carnegie. In 1881, the steel magnate wrote to the mayor of Pittsburgh and offered to donate $250,000 to the city for the purpose of creating a free library. But because the city had to come up with the land and find funds for its continued operation, it wasn’t until 1895 that the central branch finally opened. It was so well used as both a library and museum that within two years it outgrew its original space. To heat and power the planned expansion of his Carnegie Museum and Carnegie Music Hall, Carnegie ordered the construction of the Bellefield Boiler Plant. Today, the plant is owned and operated by a consortium of eight neighboring institutions. Kevin Hiles, chief financial officer for Carnegie Museums and chair of the plant’s supervising committee, ticks them off on his fingers: Carnegie Museums, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh’s main branch, Carnegie Mellon University, Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh Public Schools’ administrative building, UPMC Presbyterian Hospital, and offices affiliated with UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pitsburgh. “It’s an arrangement that collectively provides reasonably priced steam heat,” says Hiles. “We all benefit.” “We help take care of these places. The work means something because it benefits people.”

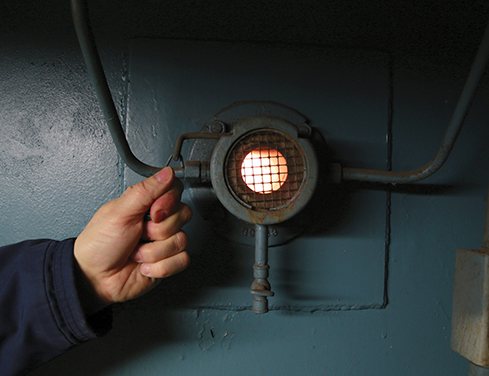

- Bob Miller, Superintendent, Bellefield Boiler PlantWhile owner representatives and steering committees chart the plant’s future, just a few people manage its crucial daily operations. Inside a large, khaki-colored brick building that looks as if it’s none of your business— a remnant of the city’s industrial heyday, maybe—the plant’s maze of pipes are visible through 19 expansive windows. As Bob Miller opens its side door, a loud mechanical hum drowns out the sound of nearby traffic. “I can walk in here and know if everything’s running normal,” he says over his shoulder, walking past boiler number seven’s wall of pipes. “I know every sound in here. If you hear something different we all look at each other and say, ‘What’s that?’ And then we all go look and find the situation.” “We” is Miller, foreman Jeff Artman, and members of Local #95, the International Union of Operating Engineers, whose motto is “Labor Omnia Vincit” or “Work Conquers All.” The plant is staffed around the clock in three eight-hour shifts by 14 union members: eight men rotate between engineer and pump man, there are two relief men for when someone goes on vacation or gets sick, and four men make up a repair crew. On a recent September morning, engineer Greg Paulowski staffs operations from a glasswalled office on Bellefield’s main floor. Because the churning sound of the plant is a little less insistent inside the booth, Paulowski keeps a pair of bright orange earplugs slung around his neck. A radio plays classic rock in the background as he points out a number on a huge monitor suspended above his head.

“See, we’re not using our full capacity— that’s the percent of what we’re using right now, 27.1,” notes Paulowski. It’s a warmish morning, he notes, a comfortable 63 degrees Fahrenheit, so only boiler three is on. “It used to be, the old-timers would try to keep it at 30 percent by adjusting the boilers because we had coal,” Paulowski explains. “Now, it’s totally automatic.” Which means while this particular function is now less hands-on, vigilant monitoring is more important than ever. If something goes amiss with the gas supply, there’s no output. Coal required more tending to keep it at 30 percent, but if something went wrong, heat would continue to come out as the coal continued to burn. “The idea of district energy is an old one whose time has come again. It’s not just because of economics, but also from a sustainability standpoint.”

- Martin Altschul, Carnegie Mellon University EngineerAll for OneWhat hasn’t changed: The three-story plant holds the potential for any number of situations. Its five boilers stamped “Erie City” can provide up to 480,000 pounds of steam an hour through common lines buried in tunnels. On the ground floor a salt tank makes brine for four water-softener tanks. Then there are the boilers themselves; the polishing tanks; the air deaerator tanks, which remove oxygen from the water. In case anything should ever jeopardize the gas supply, a 30,000-gallon, double-walled tank of oil sits under the parking lot, ready to burn, as part of the plant’s emergency action plan. If it sounds like a lot of moving parts for just 16 people to manage, Miller notes that when the plant ran on coal it was even busier. “We had to unload coal, we had to clean the boilers more often, we had to get rid of ash,” he says.

“The idea of district energy is an old one whose time has come again,” says Altschul. “It’s not just because of economics, but also from a sustainability standpoint.” District energy is essentially what it sounds like: a central plant provides steam, hot water, or chilled water to a consortium, negating the need for each building to operate its own individual system. Steam, some may be surprised to learn, is a business worth millions in Pittsburgh. There are currently five district energy systems in the city, including Bellefield, and the city is keen to develop more. “To think that a plant that was installed to make electricity and heat for the museum in the early 1900s is A) still running today and B) still providing steam and the ability to provide hot water to places here in Oakland, it’s pretty crazy,” says Tony Young, vice president of facilities and operations for Carnegie Museums. Young says he knows that most people will never know the boiler plant exists, or just how foundational it is. “You don’t think about the water in your faucet, or the electricity in your light bulbs,” he notes. “If you adjust your thermostat to get warm and it works? You don’t think about who makes it happen. Out of sight, out of mind.” Bob Miller knows exactly who makes it work. “My guys run this plant,” Miller says. He plucks at his white shirt. “I got a white shirt but I wish I had a blue shirt like the guys. We care about each other, about the community. That’s the thing I like about working here; it’s why I stay.” Outside Miller’s office window the day is beginning to warm up. But inside, on the plant’s main floor, two repairmen are already preparing for winter as they wrestle with repiping a heat exchanger. By circulating water through the exchanger and keeping it hot, Miller explains, Bellefield can have another boiler ready to provide heat in minutes. “When it rains, when it snows, when people come into the office at eight o’clock and turn up the thermostat, you have to supply more steam,” says Miller. “It’s not a surprise. We can tell what people are gonna do, and we’re ready for it.”

|

|||||||||||||||

The Elevation of Everyday Design · Taking its Bow · Art of the Now · President's Note · NewsWorthy · About Town: Changing the Conversation · Artistic License: In Full Light · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |