|

|||||||||||||||

|

Taking Its Bow

The Hill Distrit's epicenter of jazz gets its long-awaited encore at Carnegie Science Center’s world-renowned Miniature Railroad & Village®. You could hear it before you saw it. The music simply couldn’t be contained; the notes would burst out the front door and dance down Wylie Avenue. On any given night, but especially on Fridays and Saturdays, celebrities and athletes, blacks and whites, rich and poor, all dressed in their Sunday best, arrived by the hundreds.

“It was like going to church,” says trombonist and composer Nelson Harrison, who played on its stage, “a humble church with a good preacher. It was transformative. “Once you played at the Grill,” Harrison affirms, “it launched you to any stage in the world.” In its heyday—which spanned decades, as well as different locations and owners—the Crawford Grill was far more than its simple façade suggested. In addition to the world-class jazz that became its claim to fame, it was also equal parts town hall, boardroom, and bank. It was the Hill District. And now the Crawford Grill is making an encore as a permanent resident of Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village®. The task of modeling this legendary landmark is no small feat, but Patty Everly, curator of historic exhibits at the Science Center, has made a career out of taking on buildings of epic proportions. The Crawford Grill, for example, joins two other iconic Hill District monuments already on display: the original Pittsburgh Courier building, which was demolished in the 1960s, and Ebenezer Baptist Church.

In her 24 years of constructing replicas for the Miniature Railroad & Village, Everly’s credits include Forbes Field (complete with 23,000 fans made out of hand-painted cotton swabs), Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, and Buhl Planetarium. For Everly, each one is a living piece of art. “Our goal,” she says, “is to tell the story of the region up until the 1940s by creating historically, architecturally, or culturally significant sites.” Making each model is a challenge and an honor, Everly says. Infusing it with a sense of energy and life is where the real magic happens. It all starts with research. Photographs, newspaper clippings, and personal recollections of those like Harrison’s not only yield specific details but can also provide the framework for the sights, sounds, and smells that defined the experience. “We want to do justice to this special place, to its story,” Everly says. “We want to do it right.” Fortunately, Charles “Teenie” Harris, one of the principal photojournalists for the Pittsburgh Courier from roughly 1938 to 1975, immortalized the nightclub in his photographs, which are now housed at Carnegie Museum of Art. In 2001, the museum purchased the complete Teenie Harris archives of 70,000-plus images of life in and around Pittsburgh’s Hill District. “We want to do justice to this special place, to its story.”

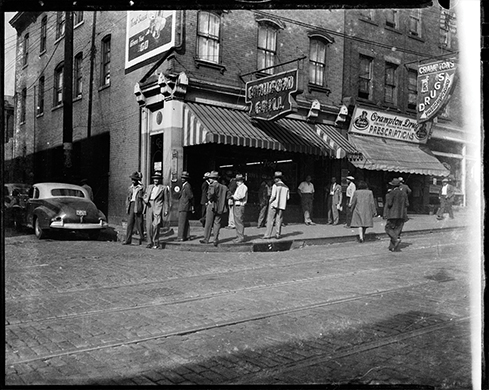

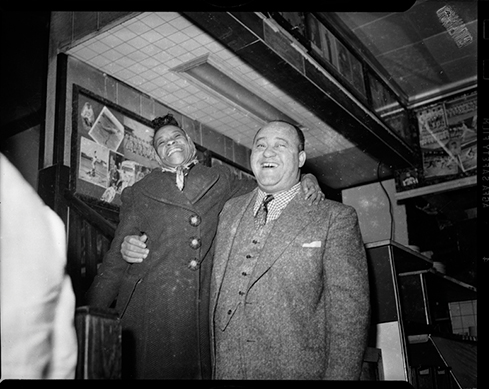

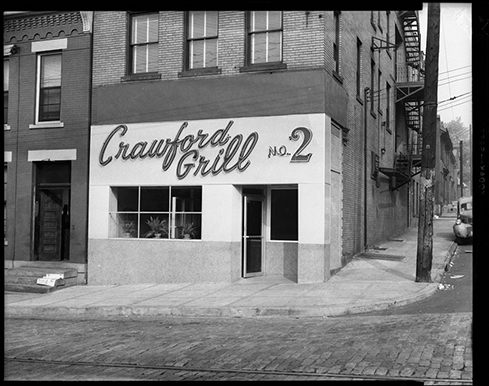

- Patty Everly, Curator of Historic Exhibits, Carnegie Science CenterIt’s the detail plucked from those images that brings the model to life: The neon Crawford Grill sign on the front of the club shines again; the scene just outside celebrates the arrival of the famous mirrored upright piano; and the sweet sounds of jazz play when the front door swings open. But no one from the community seems to remember exactly the color of the Grill’s exterior, and Harris’s images are black and white. “I’ll admit to taking some carefully considered artistic license,” says Everly, explaining that she studied the tones of the black-and-white images, comparing them to similar buildings from that era. She also sought input from her colleagues at Carnegie Museum of Art and the graphics department at the Science Center. Otherwise, she worked meticulously from Harris’s images. A Complicated HistoryThe history of the Crawford Grill can at times be more confusing than illuminating. After all, there were three iterations of the jazz hotspot, although some might say two, others four. The original—and the one the Miniature Railroad & Village is paying homage to— opened in the early 1930s on the corner of Townsend Street and Wylie Avenue in the Lower Hill. Gus Greenlee, a money lender and successful numbers runner, opened the restaurant and dance hall about the time he began turning the Pittsburgh Crawfords into a winning Negro League team. Crawford Grill No. 1 was destroyed by fire in 1951;Greenlee passed away the following year. About a decade earlier, Greenlee and his numbers partner Joseph Robinson opened a second location on the corner of Wylie and Elmore Street, just a few blocks from the original club. Robinson, followed by his son, William “Buzzy” Robinson, ran the second location for nearly six decades. Many in the community write off locations three and four as little more than pretenders. Even though Greenlee owned the North Side iteration, it never fully found its footing. The fourth spot to share the name, Station Square’s Crawford Grill on the Square, debuted in 2003. Having no ties to its predecessors, the club lasted just three years. Thankfully, part of the story of Crawford Grills No. 1 and 2 can be found among the tens of thousands of Harris’s images for the Pittsburgh Courier, at the time one of the nation’s most influential black newspapers. Among its pages, Harris documented nearly all of the notable events in the city at that time, as well as the makings of daily life, including Little League games, weddings, church groups, and life at the Grill. “That’s me on my 18th birthday,” says Dolores Slater, pointing at a Harris photo (below) that shows her sitting at the original Crawford Grill’s bar surrounded by friends and family, and a few strangers (Harris asked other patrons to join in). Slater recognizes Robert E. “Pappy” Williams, the first black magistrate in Pennsylvania, and William “Woogie” Harris, Teenie’s brother, in the back row; and of course, her mother, stepfather, and Aunt Pinkie in the front.

“It was January 21, 1946, and it was my very first time in the Crawford Grill,” Slater recounts. “My mom thought it would be a great place to celebrate. I don’t know who put that hat on me, but I remember I was wearing a Kelly-green dress with tiny gold stars and a new mouton-lamb coat. I thought I was hot stuff.” The original Crawford Grill was that kind of place—a place for special occasions. The food was “fabulous,” the atmosphere “high-class,” Slater recounts. And the music? Just a sampling of some of the headliners: Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Billy Eckstine, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzie Gillespie, Earl Hines, Lena Horne, and Sarah Vaughan. Even when a performer, white or black, was booked in a Downtown Pittsburgh establishment, an after-show Grill visit—and perhaps a jam session—was a must. Pittsburgh's Little HarlemKnown as Little Harlem, The Hill was a stop along the Chitlin' Circuit, offering black musicians traveling from New York City to Chicago an opportunity to play at safe and stellar venues. Through the 1950s, the Hill was dubbed the “crossroads of the world” by Harlem Renaissance poet Claude McKay, and was teeming with cool clubs like the Hurricane Lounge, Roosevelt Theater, Savoy Ballroom, Bamboola Club, Loendi Club, Little Paris, Flamingo Hotel, Harlem Casino, Pythian Temple, and the Black Musicians Club (Local 471). Still, Crawford Grills No. 1 and 2 stood out. Practically a full city-block-long with a big front window, Grill No. 1 had three floors. The second floor featured a glass-topped bar and a revolving stage where local pianist Alyce Brooks (and one-time piano teacher of Dolores Slater) would often play the signature mirrored upright. The third level was known as Club Crawford, a VIP lounge where Greenlee would conduct business. “There was a tradition of helping people, especially during the Depression,” says historian John Brewer. When traditional lending institutions would inevitably turn African Americans away, “Greenlee became the black bank,” he says. Greenlee’s influence was far-reaching. As the head of the 3rd ward Republicans, he had political clout; and as a lover of food, he had sway over his patrons’ palates. According to Brewer, Greenlee was one of the first to introduce the Hill to Chinese food. Food in general was certainly a part of the Grills’ appeal. The menu was diverse, ranging from frog legs to fried chicken; and by all accounts, every dish was equally delicious. “It was like going to church. A humble church with a good preacher. It was transformative.”

- Nelson Harrison, Musician and ComposerSmaller in square footage but perhaps looming larger in people’s memories, Grill No. 2 was a shotgun building—long and narrow. “As a young musician,” says Harry Clark, trumpet player and educator, “you would find your way to the Grill very quickly. The first time I went was in 1957, I was a senior in high school. The place was packed; it was hard to even find somewhere to stand. The first musician I saw there was organ player Richard “Groove” Holmes. He blew my mind.” Clark, now the president of the African American Jazz Preservation Society of Pittsburgh, became a regular and soon discovered that one of the best seats in the house wasn’t in the house at all. “I realized that if I walked around the side of the building, I could stand by an open door and see the stage and still hear the music,” he says. Pittsburgh playwright August Wilson had a similar epiphany. In his last published work, How I Learned What I Learned, he recounts joining a crowd of people outside the Crawford Grill No. 2, circa 1966, as John Coltrane’s sax inspired and enthralled. Inside, the stage was elevated and surprisingly small for the big talent it would hold. “Your head was pretty much at the ceiling,” Harrison says. “It was a great perch, you could see everything.” There was a lot to see. But sometimes people wanted to maintain a degree of anonymity. The paparazzi of the time, including Harris, would circulate through the clubs snapping photos and then selling them as keepsakes. The going rate was $5 a print, $10 to lose the negative.

The music was loud, the parking hard to come by, and the audience racially mixed. “There were fine cars parked out front and the finest ladies inside,” says Ralph Proctor, author and professor of African American history at the Community College of Allegheny College. “It was always crowded, the booths were filled, and [owner] Mr. Robinson would be sitting on his favorite bar stool.” It wasn’t unusual for the Rooneys, Kaufmanns, and even the Kennedys to show up at Grill No. 2. Martin Luther King Jr. visited, as did Frank Sinatra. Athletes like Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, and Muhammad Ali were also among the clientele. They were there to hear the likes of Chet Baker, George Benson, Miles Davis, Walt Harper, Thelonious Monk, Stanley Turrentine, and Max Roach. Proctor estimates that on some evenings it was a 60-40 ratio of whites to blacks. “The Grill provided a place of elegance in an area outsiders tended to think of as down-trodden,” he says. “One could dress in elegant outfits, hear elegant music, and eat elegant food while escaping the surrounding world filled with racial hatred. Its reputation extended far beyond its physical boundaries and many white folks came to hear the music, let their hair down, and eat the famous chicken wings. For many whites it was the first time they came to realize that we were a vibrant people full of hope and dreams despite oppressing racism.” “The Grill was a melting pot,” Harrison says. “It had a peaceful, loving atmosphere. There was never any trouble.” But trouble came to the Hill District, first in the name of progress, as urban redevelopment plans called for the creation of a new multipurpose auditorium. By the time the Civic Arena opened in 1961 in the Lower Hill, 1,300 buildings had been razed (including the original Crawford Grill), 400 businesses shuttered, and 8,000 residents displaced. “It was the worst thing that ever happened [to the Hill],” Proctor asserts. Even worse, he contends, than a week of riots that followed Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, resulting in one death, 505 fires, $620,000 in property damage, and 926 arrests. Despite the rise of the arena and the effects of unrest, Grill No. 2 continued operating, although white patrons didn’t frequent the club in the same numbers from that point forward. In 2001, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission dedicated a plaque commemorating Grill No. 2’s rich history. Today, nearly 15 years after it closed, the marker stands watch over a boarded-up, silent building. But Harrison, for one, still hears the music. “It’s playing in my head all the time,” he says. “It stays with you wherever you go.”

|

|||||||||||||||

The Elevation of Everyday Design · Art of the Now · Inside the Cloud Factory · President's Note · NewsWorthy · About Town: Changing the Conversation · Artistic License: In Full Light · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |