|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Photography by Tom Little unless otherwise noted. |

The Elevation of Everyday Design

Carnegie Museum of Art tells the unsung story of Peter Muller-Munk, a German-American silversmith whose fortuitous move to Pittsburgh in the 1930s inspired a revolution in industrial design.

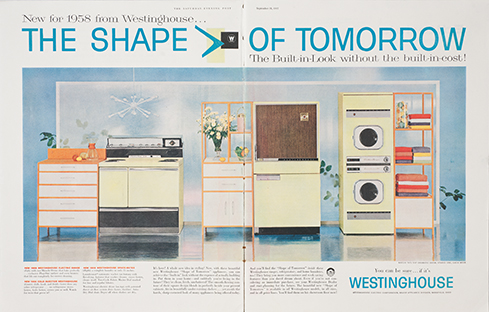

This astonishing rise to artistic stardom came to an abrupt end with the Great Depression. Knowing that he would struggle to sell luxury silver, Muller-Munk threw his creative energy into industrial design, and in 1935 he moved to Pittsburgh to take a job as an assistant professor at Carnegie Tech, today’s Carnegie Mellon University, and concurrently launched a private design practice. In the industrial heartland, Peter Muller-Munk Associates (PMMA) made its mark refashioning Schick razors, Westinghouse refrigerators, Griswold cast-iron pots, and hundreds of other everyday items that were suddenly in demand by the growing middle class of postwar America.

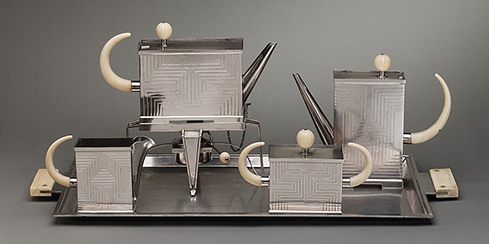

But the museum attention he received as a silversmith eluded Muller-Munk as one of the top-10 industrial designers in the country. In fact, he scolded cultural institutions, including Carnegie Museum of Art, for snubbing industrial design. Today the museum is more than making up for that early rebuff with Silver to Steel: The Modern Designs of Peter Muller-Munk, the first survey of the designer’s work, on view through April 11, 2016. The show includes more than 120 objects ranging from the designer’s best known, museum-lauded works to his creations that became everyday household staples: stylish but informal oven-to-table Griswold cookware, the Westinghouse portable radio, and the Lady Schick razor. Videos, vintage photographs, ads, and newspaper clippings add texture to how Muller-Munk helped shape industrial design as something both sleek and functional.

“He was critical of art museums only accepting product design that could pass for sculpture,” says Delphia. “He said they needed to look at other criteria; that good design is not about a toaster so stunning you can put it on your mantle and call it sculpture. It’s about bringing beauty, order, and reason to the rituals of everyday life.” Silver to Steel not only celebrates a pioneer in industrial design—one largely overshadowed by the more famous designers in New York and Los Angeles. It also highlights an untold story of Pittsburgh’s industrial past. “It’s a creative counterpoint to the industrial narrative we all know,” Delphia says. “There were wonderful consumer goods designed and created in Pittsburgh.” A Force of PersonalityInside Four Gateway Center in Downtown Pittsburgh, home to PMMA offices, a small group of office workers could often be found waiting for the elevator. As soon as Muller-Munk —a slim man in tailor-made suits, fedora, and spats—appeared, the workers would part and clear a path for him, says Paul Wiedmann, a designer and partner at PMMA. “He was critical of art museums only accepting product design that could pass for sculpture. he said that good design is not about a toaster so stunning you can put it on your mantle and call it sculpture. it’s about bringing beauty, order, and reason to the rituals of everyday life.”

- Rachel Delphia, Exhibition Co-curator“He had this composure, and people would step aside for him,” says Wiedmann, who worked at the firm from the late ’50s to the late ’90s. “He could be the last person in the group, but when the doors opened he would go in first.” His presence and gift for speaking made him effective in pitching to and securing new clients. Charming to many, he was off-putting to others. “There was a little jealousy from the other partners that he was overdoing it being European and capitalizing on it,” Wiedmann recalls. “I never looked at him that way. He was genuine Peter. He was a European aristocrat. That was just the way he was.” Muller-Munk grew up in a highly cultured home on the periphery of Berlin, in a Protestant family that had converted from Judaism. His father, Franz, was a physician and professor of pharmacology. His mother, Gertrud, was a writer and painter who attended a dress ball in 1923 and happened to meet the accomplished German sculptor and silversmith Waldemar Raemisch. That paved the way for Muller- Munk to apprentice under him for three years before moving to the United States because of tough economic times in Germany. Raemisch’s influence helped Muller-Munk develop his own style: modern, but with classical lines. “His silver was considered modern but not extreme,” says Jewel Stern, an art historian and co-curator of Silver to Steel. “It would work in a traditional home as well as a modern home. His influences were contemporary German silver as well as Scandinavian, with influences of modern silver. He mixed different motifs in a way unlike anyone else.” Beyond artistic talent, he also had a force of personality that propelled him forward quickly. “He must have had a great deal of savoir faire at a young age,” says Stern. Not only did he cause a stir in the art world, he also drew attention in his personal life when he had a scandalous affair with Ilona Loewenthal Tallmer, a married woman with two young sons. She left her husband to marry the designer in 1934. Her son, the late Jerry Tallmer, founder of The Village Voice, wrote how he remembered coming to his mother’s house and seeing the elegant Muller- Munk jump out the window and onto a neighboring roof. This undignified move was required because a court order prevented her children from seeing their mother with the man who had broken up their family.

Muller-Munk knew he couldn’t make ends meet making luxury silver. It had been hard enough to turn a profit when the economy was strong. So in the early 1930s, he moved into mass-produced goods, striking gold in 1935 by designing the Normandie pitcher for Revere Copper and Brass. The pitcher was named for the luxury ocean liner that made its maiden transatlantic voyage that June. Playing off the excitement of the voyage, Muller-Munk designed a teardrop-shaped, chromium-plated metal water pitcher. Streamlined and stately, the pitcher was so successful that its image was later put on a postage stamp honoring “Pioneers of American Industrial Design.” The designer jumped at an offer to become an assistant professor at Carnegie Tech, teaching the first generation of formally trained industrial designers, a job he knew would be Depression-proof.

He soon set up his private industrial design firm, and Ilona helped run the logistical side of the business. “They were partners in all things,” says Delphia. “He always joked that he made a lot of errors in his early days, saying: ‘I think I managed to make just about all of the beginner’s mistakes in a row. Thank heavens, Ilona saw to it that I did not make them twice.’” Muller-Munk hired top students to work at his firm, including several who would become partners. He also learned along with his students about industrial production techniques in the sooty steel town. In a class titled production methods, he and his students would visit Fostoria Glass Co., Alcoa, and other plants to learn about mass-production techniques they could use in their designs. “The companies wouldn’t have opened the door for him had he not been an academic,” Delphia says. “They would not have allowed a designer to come in and snoop.” An Inspired LeaderPMMA landed national and international clients including Alcoa, Bayer, Bell & Howell, Bissell, Mellon Bank, Pittsburgh- Corning, Silex, Texaco, U.S. Steel, Waring, and Westinghouse. Most Americans didn’t know the designer’s name, but they knew the products he and his firm designed, which filled their kitchens, living rooms, and tool sheds: the Waring Blendor, known for its skyscraper shape; home movie cameras and projectors for Bell & Howell; and the do-it-yourself-inspired, lightweight, and easy-to-use Porter-Cable electric saw. In the late 1950s, PMMA was hired to redesign Schick’s electric razors, which were newly segmented for each member of the family—including the Schick Varsity, a first razor for the “peach fuzz crowd,” and the Lady Schick.

In ads, husbands were told to buy their wives their own razor so they would never borrow theirs again. Packaged in small hat boxes, the new razors in white, pink, lipstick red, or turquoise radiated femininity. But the design went beyond mere styling. The new model had the plug on the side and a much-needed on/off switch. “It wasn’t glamorous but it made a huge difference,” Delphia says. “You didn’t have to lean over to pull out the plug to keep it from dancing all over your vanity.” Says Leonard Levitan, a designer at PMMA who is now in his early 80s: “We weren’t just making things pretty. We advised manufacturers a better way to make the product.” In his office, Muller-Munk was respected, formal, and never just one of the guys, joking around or joining the designers after work for a beer. It took Levitan about five years at the firm before he was comfortable enough to call his boss by his first name. Even with that reserve, “he was very respectful of his staff. I never saw him angry,” Levitan says. “It was a nice place to work.” As a leader, Muller-Munk would give a general vision and let the partners and designers execute it. Wiedmann recalls working on a design and Muller-Munk coming over to inspect it. “He might give general encouragement such as ‘Mr. Wiedmann, you are onto something.’” He encouraged his designers to find their muse in art museums, not in trade industrial magazines. When PMMA was hired by U.S. Steel to execute the Unisphere, the sculpture that symbolized the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, Muller-Munk gave Wiedmann inspiring advice: Go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and look at The Sun, a wire sculpture by Richard Lippold. At the same time, Muller-Munk longed for the art world to embrace a critical framework capable of appreciating a refrigerator, for example, for what it is: good design. He complained about art critics “who judged industrial products on the basis of abstract aesthetics only, as though a refrigerator were subject to the same critical approach as the Venus de Milo,” one of the most famous examples of ancient Greek sculpture.

In the environmentally conscious ’60s, PMMA entered its next phase, working with architects on urban development. The firm designed street signs and uniform symbols for restrooms. Later it helped devise wayfinding graphics inside Three Rivers and other stadiums. The firm also developed a new logo and filling station prototypes for Texaco. But as his design firm continued to flourish, Muller-Munk’s personal life unraveled. On February 12, 1967, his beloved wife Ilona committed suicide. Inconsolable, he took his own life on March 13, 1967, leaving the industrial design field with a gaping hole. Though the firm endured for 40 years after Muller-Munk’s death, it changed substantially in 1974 after it merged and became a division of Wilbur Smith Associates, an engineering and urban planning consultancy. Wiedmann keeps the memory of the dazzling designer alive with an archive of 30,000 35 mm slides and Muller-Munk’s scrapbooks— artifacts that have greatly informed the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue. “In my lifetime, I will never meet another man like Peter,” Wiedmann says. “He was from an era that is gone.” Support for Silver to Steel: The Modern Designs of Peter Muller-Munk is provided in part by the Kaufman Endowment; the Henry L. Hillman Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art; Richard, Priscilla, Bill, and Janet Hunt; Trib Total Media; the Alan G. & Jane A. Lehman Foundation at the request of Ellen Lehman and Charles Kennel; the Bessie F. Anathan Charitable Trust at The Pittsburgh Foundation at the request of Ellen Lehman; Edith H. Fisher; the Alexander C. & Tillie S. Speyer Foundation; Richard L. Simmons; The Roy A. Hunt Foundation; The Barrie and Deedee Wigmore Foundation; Macy’s; Wells Fargo Advisors; and an anonymous donor.Lead image at top: Peter Muller-Munk Associates, Bell & Howell Company, 16mm movie camera, 1957, Carnegie Museum of Art, Promised Gift of Jewel Stern; Griswold Manufacturing Company, Symbol pot #91, 1962, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Jewel Stern. Image courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art, Photo: Brad Flowers; Schick, Incorporated, Schick Powershave, 1957, Lady Schick Futura, 1958, and Schick Varsity, 1957, electric shavers, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Jewel Stern; Wayne Pump Company, Wayne 500 gas pump, 1950 (restored), Carnegie Museum of Art

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Taking its Bow · Art of the Now · Inside the Cloud Factory · President's Note · NewsWorthy · About Town: Changing the Conversation · Artistic License: In Full Light · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |