|

||||||||||||||

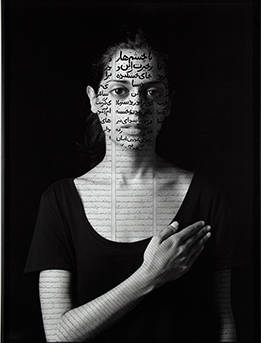

Lalla Essaydi, Bullet Revisited #3, 2012, Courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, NY. Yezerski and Miller Gallery, Boston |

Visually Telling

In striking photographs, 12 female artists give voice to contemporary life in Iran and the Arab world. Lebanese-born photographer Rania Matar was living the American Dream, she would say, when the terrorist attacks of 9/11 gave her great pause. “All the news coming out of the Middle East was very negative. The Lebanon I knew and the people I knew were not what was being described on the radio or TV,” she says. “It was always them and us. This, for me, was a big identity moment—I am them, and I am us. How do I fit in here?”

Matar had been on the radar of Linda Benedict-Jones, the recently retired curator of photography at Carnegie Museum of Art, for years. In 2014, Benedict-Jones happened to visit Matar at an exhibition of her work in Boston when the artist mentioned she was also part of an exhibition of contemporary works by women photographers from Iran and the Arab world at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). Off Benedict-Jones went the next day to see the show, She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World. The first thing she noticed was the large crowd—not always a sure thing for an exhibition on a weekday. “Within a very short time I realized that I was in an exhibition that was going to truly captivate me,” she says. “As a veteran curator, I’ve seen hundreds of photography exhibitions and I was immediately engaged in what I was looking at. The material was so fascinating. “Each of the bodies of work is unique. I don’t consider myself as being particularly provincial, but I realized I was in a very foreign place at this exhibition—because I was seeing a culture and a perspective that was entirely new for me. It was the perspective from the inside, from women who are in Iran and Arab countries. This is a completely fresh exhibition for Carnegie Museum of Art.” She Who Tells a Story, on view in the Heinz Galleries through September 28, was conceived and curated by Kristen Gresh, the MFA’s Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Assistant Curator of Photographs, who had followed the work of contemporary Middle Eastern photographers while she lived and worked in Egypt and Paris. Gresh initially envisioned a group of six to eight artists, but as she made new discoveries the show grew to a dozen. “I did make a conscious choice to choose photographers who were looking at the complexity of identity and the multiplicity of different identities within the region,” she says. “And I wanted to include a range of work from what one might consider fine art photography to documentary.” A woman’s worldSome of the most sumptuous and complex images in the show are those created by Moroccan-born painter and photographer Lalla Essaydi. Many of her works feature meticulously created landscapes of walls and textiles—every inch of which has been embellished by lines of Islamic calligraphy. Essaydi, who divides her time between Morocco and the United States, gathers women from her community to work collaboratively on creating the labor-intensive backgrounds and textiles for the photographs. Against these settings, some of which take up to a year to prepare, are posed female figures draped in robes and veils. The artist also applies calligraphy—exhaustively so— to both clothing and flesh. The result is fascinating, exquisite, and suffocating. “What drew me in first years ago—and continues to—is this inner world of one person’s story,” says Catherine Evans, the Museum of Art’s chief curator, who in 2005 presented Essaydi’s first solo museum exhibition, Converging Territories, at Columbus Museum of Art. “I think we as Americans have a lot of misperceptions about the Middle East and how women function in those cultures. Lalla’s work is one of a dozen ways to understand it more fully.” “I think we as Americans have a lot of misperceptions about the Middle East and how women function in those cultures.”

- Catherine Evans, Chief Curator of Carnegie Museum of ArtEssaydi’s use of calligraphy is laden with significance. Islamic calligraphy is a sacred art practiced by men for religious texts. It’s also written in henna dye, used by women to mark important moments in a woman’s life. Essaydi twists and intertwines these traditional, gender-specific practices. The writings in Essaydi’s photographs are diaristic, Evans says. “It’s very personal—a stream of consciousness about these women’s lives. But we wouldn’t know that unless we understand the language. So there’s a kind of mystery to the work as well.” In her more recent Bullet series, Essaydi brings incongruous elements together to dazzling and disturbing effect. Her huge 5-by-12 foot triptych, Bullets Revisited #3, again employs hennaed calligraphy on the clothes and body of a female figure who lies in repose, her long hair flowing to the floor. If the pose seems vaguely familiar, it’s because Essaydi is responding to 19th-century Orientalist paintings, Gresh points out—the Western fantasy of the harem and concubine. The walls, linens, and clothing of the figure seem at first to radiate with the gleam of gold. What is glittering are thousands of carefully arranged bullet casings. “She had people going out to the Algerian- Moroccan border and collecting bullets, and then she was having them cut and sewn to the textiles,” says Gresh. “She’s very aware of and interested in the beauty of Moroccan architecture and tile. Here, she’s taking these bullets fraught with contemporary politics and recreating this decorative background and having the bullets become jewelry. She’s talked about being concerned about the role of women in this post Arab-Spring era, but she’s still remaining connected to her continual questioning of gender roles in her culture.” New documentaryOne of the most well known artists in the exhibition is Iranian photographer and filmmaker Shirin Neshat, who local audiences may recall from the 1999 Carnegie International. Neshat also employs calligraphy, but to different effect. In her striking, black-and-white portraits of men and women, she superimposes careful, elegant lines of calligraphy—contemporary and epic Iranian poetry—across the face and body of each subject.

This includes Shadi Ghadirian and Gohar Dashti, both of whom live and work in Tehran. The pair is part of a group in the show that Gresh calls “new documentary.” She explains it this way: “They’re making reference to a direct experience they lived through, but they’re staging these photos in interesting ways.” In Ghadirian’s Nil, Nil series, the photographic clarity of her still-life images is the first thing you notice. But what stuns you a heartbeat later are the bullets nestled among the lipstick, jewelry, and gold nail polish spilling out of an expensive evening bag, or the grenade laying among the apples, grapes, and oranges. That intrusion of military conflict into daily life is also explored by Dashti, who grew up near the Iranian border during the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s. “Gohar [Dashti] actually talked about how they’d go to school and have to go to some sort of bunker,” Gresh says. “Or she’d be with her family in a shelter and her mother would say, ‘Well, we’re going to celebrate your birthday, or New Year’s, right here right now.” In Dashti’s Today’s Life and War series, one image shows a young couple in a desolate landscape hanging laundry on twists of barbed wire. In another, the same couple, dressed in wedding attire, stares passively from the front seat of a burned out car that has been festooned with pink and white ribbons and bows. The image of the couple celebrating the Persian New Year with a makeshift table bearing traditional symbols—apples, a mirror, a goldfish in a bowl—parallels Dashti’s real-life experience, Gresh says. The “table” is a cloth on the ground. Scattered around the landscape are army helmets. “All of these are poetic and beautiful images, but always interrupted by some symbol of war,” says Gresh. “I think they’re really about perseverance and determination.”

“All of these are poetic and beautiful images, but always interrupted by some symbol of war. I think they’re really about perseverance and determination.”

- Exhibition Curator Kristen Gresh on the work of Gohar DashtiSomething to sayWhile much of Rania Matar’s work is in black and white, the series that represents her work in this exhibition, A Girl and Her Room, is in vivid color. In Christilla, Rabieh, Lebanon, the saturated, hot pink walls frame your attention, drawing your eyes to the larger-than-lifesize print of Marilyn Monroe swathed in white silk sheets that dominate the wall, and then your eyes drop to the teenager whose dyed blonde hair is almost as platinum as that of the actress. She is slung sideways in a modern chrome and leather chair, her eyes resting just south of a direct challenge to the camera. Further visual treats await. The kelly green Crocs the girl has just shrugged out of. A pink bra, just one sliver of a shade less feisty than the walls, hangs from the key to the flawless white closet door. A straggle of dress sandals, heels, and slides share careless floor space with a small, worn, stuffed hippo. “I’m not interested in girls around the world. For me, including girls from Lebanon and Palestine and the Middle East and the United States is part of my identity. This is personal.”

- Artist Rania MatarThe question of Matar’s identity is intertwined with the work. “I realized I was exactly like those girls—25, 30 years earlier —growing up in Lebanon,” she says. “It was again the universality of time and space; it didn’t matter. There’s something so similar about all those girls at this moment in their lives.” The project took her back to Lebanon, as well as to the West Bank and even the Palestinian refugee camp.

“I’m not interested in girls around the world,” Matar says. “For me, including girls from Lebanon and Palestine and the Middle East and the United States is pretty much part of my identity. My father was originally Palestinian. This is personal.” Shirin Neshat has said, “I don’t think an artist should make a mark unless they have something compelling to say. I feel strongly that you cannot make work about a subject unless you have experienced it yourself.” The artists of She Who Tells a Story have much to say. The work of these powerful female image makers invites viewers, perhaps for the first time, to encounter their world through their eyes. Major support for She Who Tells a Story is provided by Cathy Raphael, Ritchie Battle, Susan and John Block, the Jack Buncher Foundation, Gordon and Kenny Nelson, and Alex Paul. This exhibition is organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

|||||||||||||

Saving the Songbird · Before They Were Famous · Cosmic Bling · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Cecile Shellman · Artistic License: Born to Paint · Science & Nature: Making It Count · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |