Summer 2015

Summer 2015|

Born To Paint

A true original, Jacqueline Humphries takes her signature silver and black-light paintings in an imaginative new direction. At times, as she paints inside her Brooklyn studio, Jacqueline Humphries feels a bit like a mad scientist, her creativity bouncing from one canvas to the next, one painting beginning where the last one left off.

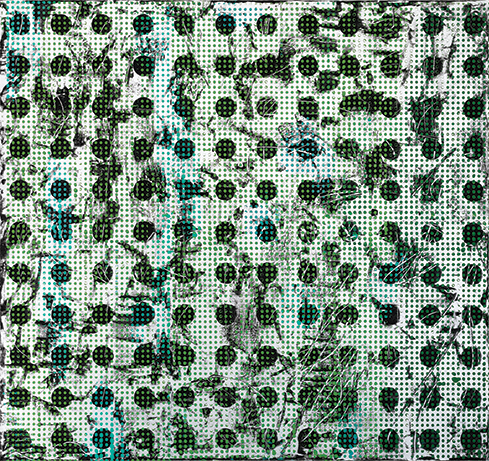

“It’s almost like I’m breeding paintings more than painting them,” she says with a laugh. “The paintings kind of reproduce other paintings. I might try to make three paintings three times but alter one thing. It seems like selective breeding in a way.” One of the most inventive abstract painters of the last 30 years, Humphries will debut her first solo museum show in a decade at Carnegie Museum of Art from June 11 to October 5. The entirely new body of work has an industrial vibe, showcasing the custom-made stencils of dots, emoticons, and other images she creates in her studio using a giant stencil machine. She often uses metallic pigments with the stencils, creating a shimmering effect. In other works, she paints with ultraviolet hues that glow like fun-house images under black light. “It’s an exciting new direction combining more of a machined aesthetic with gestural markings to create layered planes of gridded forms,” says Amanda Donnan, assistant curator of contemporary art at Carnegie Museum of Art and organizer of the exhibition. “And when she uses emoticons together with this sort of hollowed-out language of abstract expressionism, it becomes, as she’s called it, a ‘conspiracy of two inadequacies.’” Emoticons, plucked from the ubiquitous cell phone, are playful, grating tech images. “Emoticons are annoying. We all hate them but we all use them,” Humphries says. “Emoticons are all about facial expressions. What would it be to import that into painting?” Humphries has also created stencils from the weave of canvases: She thinks of stencils as a kind of “DNA” that can be reproduced and then tweaked for the next work of art. Unlike the decorative stencil designs of Martha Stewart, Humphries’ creations are not cookie-cutter perfect. She delights in messing them up. “I never use the stencil and leave it,” she says. “It’s something to work against. Let’s say I stencil a pattern onto canvas and it’s perfect in its own way. I ruin it. I violate its regularity, wiping it completely, smearing it, painting over it.” A movie buff, Humphries paints with pigments that reflect the light around them, changing like cinematic frames as the visitor moves before the large 9-by-9-foot canvases. The silver metallic paintings will be mounted in the museum’s Forum Gallery, across from a bank of windows, the summer sun creating glistening and shifting patterns. Installed next door in the Coatroom Gallery will be new black-light paintings, one of Humphries’ signature bodies of works. Like visitors to a haunted house, museumgoers can laugh at their glow-in-the dark socks and teeth as they peer at the glowing abstract art. “It’s flirting with ‘low’ cultural forms like a carnival fun house and black-light posters, and combining it with high Modernism,” Donnan says. Humphries has always forged her own artistic path. A native of New Orleans and a daughter of artists, she discovered art in seventh grade at Metairie Park Country Day School, which had a progressive art program. “Let’s say I stencil a pattern onto canvas and it’s perfect in its own way. I ruin it. I violate its regularity, wiping it completely, smearing it, painting over it.”

- Jacqueline Humphries“I found school to be a pretty alienating experience,” she says. “I discovered the art facility and teachers, and then school became a fun place to go every morning.” Becoming an artist seemed natural. “No one ever said, ‘Here, make a painting.’ But my mother is an artist who makes jewelry. Art was all around me.” After studying art at Parsons School of Design and the Whitney Independent Study Program, Humphries started her career in the ’80s, a difficult juncture for her medium. Painting had been declared dead, and more conceptual approaches to art-making were in vogue. “Painters were hated,” she recalls. “People were so intense about it. It was such an intense feeling to the point of saying I shouldn’t be doing it. The whole critique of painting—I thought this was describing some environment of extreme doubt that I can adapt to painting. That gave me new things to work on.” Not that there weren’t some uncomfortable moments in galleries. “I was terrified by some other artists,” Humphries admits. “Critics wouldn’t even bother with you. With artists, there are camps and allegiances. It’s just like middle school, very cliquey. It comes to the point where you can go with cool people but lose who you are. Maybe you should just stick to your guns and wait and see what happens. I wasn’t about to run away and do the right thing.” Sticking to her own ideas has paid off. And so has a strong work ethic. “No matter what kind of mood I’m in, I go to the studio,” she says. “Inspiration in art is overrated. Artists just go to work like anyone does.” Humphries has been working furiously for months preparing simultaneously for two solo exhibitions—one at Carnegie Museum of Art and another in her gallery, Greene Naftali in New York. “I love the Carnegie so much,” she confides. “It’s such a great museum. I love Pittsburgh. I am so honored to be in such a venerable, great institution.” The pair of shows has the artist working overtime. After months of trial and error during the early stages of creation, the finality of a deadline has helped focus her work and take her to new places. “I get really excited near the end,” Humphries explains. “It seems to flow better. A 12-hour day can seem like it went by in five hours. Being close to deadline allows me to cast aside all doubt. The direction is there. Just go for it! I get this feeling of velocity. The work is pulling me along rather than me pushing it. All the energy I put into the work starts to give back and I feel my job is easier. Why shouldn’t it be easy? It shouldn’t always be hard.” Major support for Jacqueline Humphries is provided by the Juliet Lea Hillman Simonds Foundation, Jill and Peter Kraus, Christopher M. Bass, Wendy Fisher, Candy and Micheal Barasch, The Benjamin M. Rosen Family Foundation, the Ruth Levine Memorial Fund, and Greene Naftali, New York.

|

Saving the Songbird · Before They Were Famous · Visually Telling · Cosmic Bling · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Cecile Shellman · Science & Nature: Making It Count · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |