|

||||||||||||||||||

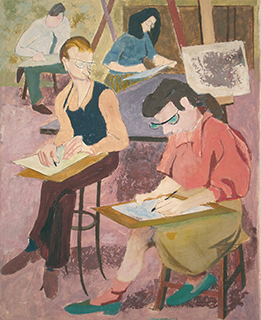

Philip Pearlstein, Merry-Go-Round, 1939–40, Courtesy Betty Cuningham Gallery |

Before They Were Famous

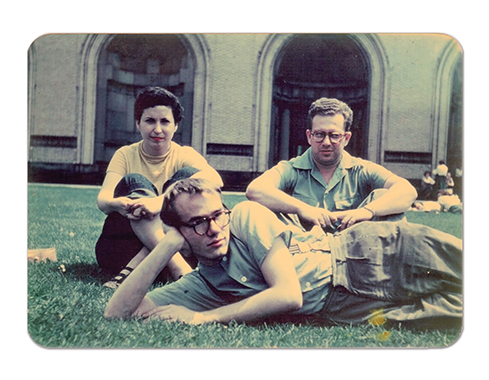

Famed painter Philip Pearlstein recalls his early connection with Andy Warhol, and the diverging paths that led each to his own unique place in art history. Philip Pearlstein readily acknowledges that most of his contemporaries are no longer “upright.” But by all accounts, the 91-year-old painter is still standing—and hardly standing still. He’s just completed a new series of work that figures prominently in Pearlstein, Warhol, Cantor: From Pittsburgh to New York, a first-of-its kind exhibition on view at The Andy Warhol Museum through September 6.

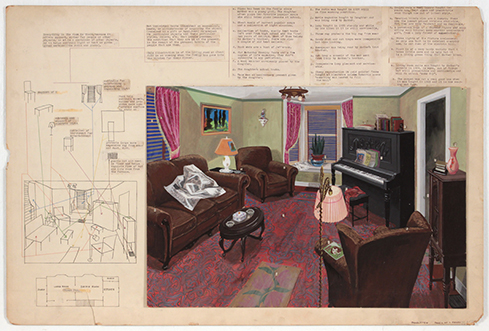

Through artwork and photographs, the show tells the classic tale of three working-class kids growing up in a relatively small town who decide to move to the big city to pursue their ambitious dreams. Along the way, they find love, success, and, ultimately, perspective. “Those nascent years when things were just starting to form is a narrative that hasn’t been told before,” says Jessica Beck, the museum’s assistant curator of art and the exhibition’s co-curator along with The Warhol’s chief archivist Matt Wrbican. With more than 50 paintings and drawings and a slew of period photographs, the exhibition provides a rare glimpse into the artists’ early years. It is precisely that long look back that allows visitors to follow the divergent paths that Pearlstein, who would become known for his Modernist Realism nudes, Andy Warhol, and the lesser known Dorothy Cantor took to find their creative footing. Cantor, a talented painter and artistic trailblazer in her own right, ultimately chose family over career. Their collective story begins in the East End of Pittsburgh. Pearlstein grew up in the city’s Greenfield neighborhood and graduated from Taylor Allderdice High School; and, like Warhol (who lived in South Oakland), he took Saturday classes at Carnegie Museum of Art. But it wasn’t until 1946 that these aspiring artists (Cantor lived in Squirrel Hill)met on the campus of Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, where they trained with the likes of artist and designer Robert Lepper, one of Pittsburgh’s pioneer Modernists, and Samuel Rosenberg, a beloved instructor and one of Pittsburgh’s most important 20th-century artists.

“He asked me, ‘How does it feel to be famous?’” recalls Pearlstein of their initial encounter. “My spontaneous answer was, ‘It only lasted five minutes.’ During the next three years, Andy’s easel remained next to mine in painting and life-drawing classes.” The two became close, attending the Pittsburgh Symphony weekly with their circle of friends and setting their sights on New York. A wartime educationAlthough they were both sophomores at the time, Pearlstein was a seasoned veteran who was returning to college on the GI Bill. After his freshman year, the 19-year-old had been drafted into the infantry and shipped off to Italy, where he was stationed in Naples, Rome, and eventually Florence. “Every day I was ready to go into battle,” he says. But fortunately his skills as a rifleman were never tested. Instead, his penchant for layout, drafting, lettering, and sign painting were put to use. In fact, as the exhibition shows, Pearlstein became quite accomplished at illustrating the finer points of bayonet practice and weapons assembly and drawing map symbols. He also kept a diary, not of stories but of images. His realistic ink drawings featured the day-to-day lives of his fellow soldiers and local villagers. When he wasn’t creating art, he was experiencing it in a way that’s almost impossible to imagine now. Despite the devastation that engulfed much of the country, Pearlstein managed to see Da Vinci’s The Last Supper and visit the Sistine Chapel where he recalls lying on his back, looking heavenward. “No one else was there,” he says. “I had it all to myself.” The fighting finally stopped. And as fear began to surrender to hope, practically every town in Italy held an exhibition to once again bring to light the works of art that had been hidden away. Pearlstein took in as many openings as was humanly and logistically possible. “I still have all the pamphlets to those shows,” he says. He looks back at this time in his life as the renaissance of his artistic sensibilities. “I think the major difference between me and Andy were those three years I was in the Army,” Pearlstein asserts. “I got this intense art education.” The more he learned, it seems, the more he felt connected to the past, or as he likes to say, “to keeping the art of those long-dead men alive.” From Pearlstein’s perspective, “Art history is very important. Nothing just springs from the air, it all has a basis in facts.” Warhol, he notes, wasn’t as inclined to look to history for his inspiration. He was much more invested in the present, and the future. “For Andy, it was all new,” Pearlstein says. “His work had an inventiveness— make it up as you go along.” Although the two remained close throughout their college days (Cantor, a year behind, quickly became an integral part of their inner circle), their styles were worlds apart. The way they approached similar subjects and course assignments—some for Robert Lepper’s classes—is strikingly different. The exhibition brings this point into sharp focus with rarely-seen early works including Warhol’s Nosepicker and Kids on Swings and Pearlstein’s Artist’s Parents and Family Picnic. “Andy’s work is whimsical, fanciful,” co-curator Beck observes; “Philip’s is mechanical, precise.” But that’s not to say their styles were fully formed when the pair graduated from Carnegie Tech in 1949. Pearlstein was just 25, Warhol was about to turn 21; they were still growing, experimenting, and readying to take on the world. “Warhol didn’t just spring up one day with the Campbell’s Soup Can,” Beck adds. “There really was a path, and this exhibition not only shows the work, but the volume of work.” Going their own waysWithin weeks of graduation, the duo followed through with their plan to move to New York and share an apartment, first a roach-infested sublet in the city’s East Village arranged through a friend of Carnegie Tech professor Balcomb Greene, and then an apartment on West 21st Street. They traveled overnight by Greyhound bus, splurging for a taxi to reach their sixth-floor apartment, all of their belongings in shopping bags. Among his fondest memories, Pearlstein recalls Warhol listening endlessly to a recording Pearlstein bought of Edith Sitwell reciting her poem Facade to the music of William Walton, and an album of Bessie Smith’s last recordings. “His favorite number started with the line ‘Gimme a pigfoot and a bottle of beer,’” Pearlstein wrote in a chapter of his autobiography still in the making and published last year in ArtNews. Back then, the city was abuzz with Abstract Expressionism personified by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Pearlstein was intrigued. His landscape paintings of rocks and cliffs infused his Realism with abstract patterns. His 1952 Superman could even be viewed as a precursor to Pop art, a genre his roommate would soon come to define. “Andy’s work is whimsical, fanciful. Philip’s is mechanical, precise.”

Jessica Beck, THe Warhol's Assistant Curator of ArtPearlstein admits that those forays into emerging trends were just that—relatively brief surveys of uncharted terrain. “I could never be truly abstract,” he says. “My work was always based in landscape.” Pearlstein initially envisioned himself as an art director, which he now acknowledges as a bit “arrogant” for a kid just out of college. His early door-knocking and cold-calling exploits support that assertion. “My illustration projects were too ambitious and intellectualized,” he wrote. “They seemed to arouse latent hostility on the part of the art directors who looked at my portfolio. One famous art director of a high-fashion magazine told me he wouldn’t hire me even to do paste-ups because my ‘virility showed up in everything I touched.’” Pearlstein did land a steady gig for an architectural catalog (it was similar to the Alcoa work he did as a student freelancer for Lepper), and he enrolled in the graduate program at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts.

Meanwhile, Warhol spent his early New York years soaking in the art of commercial illustration and experimenting with his blotted-line technique—and making a memorable impression on potential employers. “It was hot that summer, long before air conditioning came into use,” Pearlstein wrote of their first year in the big city. “Andy’s main interview clothes were a heavy white corduroy jacket and trousers, and he always wore a bowtie. On his first appointment, he told the receptionist that he was about to faint and asked for a glass of water. The whole staff scurried around to make him comfortable. He wondered if he could use that routine again. “On Andy’s fourth or fifth day of interviews,” Pearlstein continued, “he landed a major assignment for an important fashion magazine: a full-page drawing of several women’s shoes on the rungs of a ladder.” It was the start of what would become a lucrative career for Warhol as a commercial illustrator. A third actUpon her own graduation, Cantor joined her friends in New York and secured professional representation. Not long after, she and Pearlstein married, with Warhol as a member of their wedding party. By the time the couple welcomed their first child, William, in 1957, Cantor chose to commit herself full time to the family. The pair would have two more children, Ellen and Julia, and eventually two grandchildren.

“Dorothy was among the first New Realism artists,” Pearlstein says. “I’m thankful she’s receiving this attention. Between the two of us, she actually had the better career back in the ’50s.” As the ’60s approached, Pearlstein completed his master’s degree in art history and earned a Fulbright grant for painting that took him back to Italy for a year. Instead of writing postcards, he painted his Roman ruins series. When he and his family returned to New York in 1959, the rest of his life began in earnest. In addition to keeping pace with gallery showings, he got a day job as a professor, first at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute and then at Brooklyn College where he would stay for the next 30 years. As a result, his evenings were filled with painting, leaving him little time for other pursuits, including his friendship with Warhol. “Dorothy kept in touch with Andy by phone, but our connection faded,” he says. “Andy liked to have long conversations and I was too busy. Our lifestyles were totally different.” “I lose myself in the object. I become the object. For me, the adventure is in the doing. I don’t know what it will look like until it’s done.”

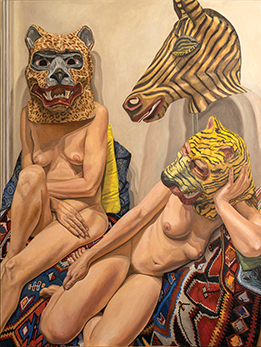

- Philip PearlsteinWarhol was preparing to introduce the world to Pop art and open the doors to The Factory, while Pearlstein was returning to his artistic roots through the exploration of the human form. He became known for what was then considered radical—his ability to paint dispassionate, realistic nudes in a way that is reminiscent of landscapes. “It’s an unemotional style, all based on visual observations,” he explains. “I want to work with what I see.”

“It’s systematic, analytical. It’s all encompassing,” Pearlstein says. “I lose myself in the object. I become the object. For me, the adventure is in the doing. I don’t know what it will look like until it’s done.” And he’s not done yet. His current work integrates hand-painted, papier-mâché masks of animal heads into his human landscapes. He discovered the colorful masks on the Internet and liked the way they looked, so he ordered them as decorations for the house. Now they’ve not only found their way into his paintings, several of those paintings will be in the exhibition. “‘Coda’ is the perfect word for these new works,” Beck says. “It is a final, dramatic coda. He’s going to a place he’s never been before.” That begs the question: If Warhol was alive today, where would he be going? Pearlstein’s answer is basically the same as it was when they were classmates and friends back in Pittsburgh. “I have no idea what Andy would be doing.” Major support for Pearlstein, Warhol, Cantor: From Pittsburgh to New York is made possible through the generous support of The Fine Foundation and Henry and Gilda Buchbiner Family.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Saving the Songbird · Visually Telling · Cosmic Bling · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Cecile Shellman · Artistic License: Born to Paint · Science & Nature: Making It Count · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |