|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| There’s a real art to collecting, installing, packing, shipping, storing, and preserving works of art. The Museum of Art reveals some of its behind-the-scenes stories.

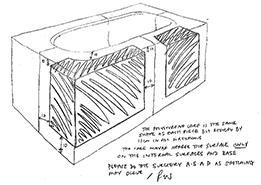

On the heels of becoming the first woman to receive Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize, contemporary sculptor Rachel Whiteread was a featured artist in the 1995 Carnegie International. She had burst onto the contemporary art scene three years earlier with her imaginative public sculpture House, a life-sized cast of the interior of a condemned three-story home in London’s East End. To achieve this, she sprayed liquid concrete into the building’s empty shell and then peeled away the house, brick by brick. For Carnegie Museum of Art’s exhibition she again cast an architectural void, this time creating colorful resin molds of the space beneath 100 chairs. The curator of the show described the rows of solidified jellies as “a field of translucent abstractions.” A year later, the museum acquired a new sculpture comparable to that larger work. In Untitled (Yellow Bath), Whiteread again created a positive from a negative by building a frame around an inverted cast-iron bathtub and, using a rubber-polystyrene mix, cast the space surrounding the tub rather than inside it. The museum was thrilled to add to its collection its first example of the artist’s ongoing investigation of domestic objects and the spaces they inhabit. There was just one interesting twist: The sculpture, Whiteread informed the curator, would need to be burped. As it turns out, the two-part urethane rubber that Whiteread used to pour over a polystyrene core created gaseous bubbles that became trapped in the mixture once it congealed—a chemical reaction that, over time, causes the sides of the sculpture to bulge. To remedy it, the artist’s assistant recommended that the museum’s conservator use a drill bit to pierce the bubbles and release the gas, in effect “burping” the work. Whiteread followed with a handwritten letter and drawings, outlining how and where to puncture the sculpture in a way that wouldn’t compromise it or be visible. At her urging, the conservator “drilled for gas” the following year, and the sculpture continues to be monitored today.

Beginning March 9, the Museum of Art will tell the stories behind Whiteread’s tub and eight other works hidden away in the museum’s stored collections in a nine-week exhibition titled Uncrated: The Hidden Lives of Artworks. Each week, museum staff will remove a new artwork from storage and put it on view in Heinz Gallery A where they'll share what's unique about it, and complete certain necessary work—update its condition report or in some cases more fully document or re-crate the object—all under the watchful eyes of visitors. As part of an overall evaluation of the permanent collection, the museum is conducting an overhaul of the storage space that currently houses these objects, along with 130 other works, the majority contemporary art. Initiated by Kurt Christian, the museum’s chief preparator, Uncrated is a byproduct of this behind-the-scenes reorganization that, under normal circumstances, would go unnoticed. “I threw it out there that the public loves this stuff, to get a glimpse of what’s not on view,” he says, noting “visible storage” is increasingly popular among American museums and their visitors. Other staff quickly jumped onboard with the idea, and as part of the experience they’ll even invite visitors to explore the tools of the trade by completing, for example, a condition report for an artwork and then comparing it against the real deal from a museum registrar. “It’s a peek behind the curtain,” says Catherine Evans, the museum’s chief curator. It takes a villageWorking most often behind the scenes, a team of registrars, conservators, preparators, art handlers, and curators orchestrate every artwork’s strategic—and tedious—journey from acquisition to public display or storage. Together, they buy, ship, receive, unpack, inspect, record, track, monitor, treat, install, store, and interpret the treasures of the museum. As of early February, there were exactly 29,778 works in the museum’s collection (not including the 73,465 photographic negatives in the Teenie Harris Archive). Only 7 percent of the collection—roughly 2,100 objects— is on view at any given time. (This perhaps surprising statistic isn’t just a practical reality at the Museum of Art; The Louvre has room to display about 8 percent of its permanent collection, and the Guggenheim 3 percent.) And as Uncrated will reveal, museum objects—even when not on display—have lives. They go out on loan, they age, and they take up space. “I’ve got wrinkles, they’ve got cracks,” quips Ellen Baxter, the museum’s chief conservator, when asked about the responsibility of caring for the museum’s 1,361 paintings, Baxter’s specialty. As Uncrated will highlight, very large paintings such as Joan Miró’s Queen Louise of Prussia present unique challenges not only related to their care, but to their shipping, storing, and installation. At some point, records show, Miró’s painting—its vibrant colors and bold composition frequently showcased just inside the museum’s main entrance—was removed from its massive stretcher frame and rolled up. It arrived at the museum this way for display in the 1967 Carnegie International, leaving dents across its surface that conservators continue to contend with today. “It’s a peek behind the curtain.”

- CATHERINE EVANS, THE MUSEUM OF ART’S CHIEF CURATOR“Paintings have a memory,” Baxter says. “Like when you wear a pair of pantyhose and you take them off, you never get them back in the same shape. Despite our efforts, this happens with paintings because of their physical nature.” The sheer length of their stretcher bars also make such huge paintings more prone to warp with seasonal changes, Baxter says. Others from the collection that pose similar challenges: Christopher Wool’s oversized panels, which hang at the museum’s courtyard entrance, and Stuart Davis’ Composition Concrete displayed in Scaife Gallery 12, one of the few contemporary gallery spaces tall enough to accommodate it. But perhaps the greatest challenge of all: moving these massive works and hoisting them onto or off the wall. For the Miró, which includes a decorative frame that alone weighs hundreds of pounds, it was a task that used to require every art handler on staff.

Recently, with a repeat performance looming, Christian joined forces with preparator Steve Russ to devise a custom solution based on a design from the National Gallery in London: a cart that can accommodate paintings up to 16 feet tall. Art handlers lift a platform to the painting’s level with a forklift, strap the artwork onto its supports, then they lower the cart to the ground and wheel the artwork to its next destination. In Uncrated, the cart cradling Queen Louise of Prussia is a co-star of the story. “A large part of what we do is problem solving,” says Christian, who oversees a staff of six charged with working hand-in-hand with museum registrars and curators to safely crate, transport, install, and store artwork. “We rotate work in the galleries constantly. Visitors see that and they think, ‘Oh, those are the art installers.’ They don’t realize all of the other stuff we do behind the scenes that goes into caring for the work before it can get to the point of going on view.”

It’s certainly challenging juggling the needs of the artwork, curators, and artists, says Craig Barron, associate preparator who has worked at the museum for a decade. But there are definite perks for this group of craftsmen, who are themselves all artists. “I’ve moved a billion dollars’ worth of artwork,” Barron says. “Icons in art history that we’ve all studied in school—we get to hold them.” Does he have a favorite? “Our Monets would be a good start,” he says without hesitation. Of the time and tasteWhen Savage State, a painting by Belgian artist Pierre Alechinsky, takes its turn in the spotlight as part of Uncrated, it will be the first time in more than a decade the museum has displayed any of its 94 paintings, prints, and drawings by the artist. Alechinsky, a name many art lovers may be hard-pressed to recognize, is second only to Pittsburgh painter and teacher Samuel Rosenberg as the contemporary artist the Museum of Art has collected most in depth. How that happened points to a turbulent period in the history of the Carnegie International and the challenges of collecting the “old masters of tomorrow,” as directed by Andrew Carnegie himself in 1896. In the late 1970s, after a string of Internationals flopped with the critics, then museum director Leon Arkus and an advisory committee of three other museum directors broke with the art survey’s tradition and focused the 1977 Carnegie International on the work of a single artist, Alechinsky. During his tenure, Arkus acquired a total of 84 works by the artist, a founding member of an international group of post-war artists known as CoBrA who were interested in gestural abstraction (when paint is spontaneously dribbled, splashed, or smeared onto the canvas). The risky move did not pay off, explains Amanda Donnan, assistant curator of contemporary art.

“This big pocket of works by Alechinsky, who is not often exhibited outside of Europe, is telling,” she says. “The museum’s collection largely reflects its exhibition history, for good and bad, and the tastes or proclivities of certain individual curators or museum directors.” The story of Savage State and the ’77 International is ultimately the story of a museum whose acquisitions in the 1960s and ’70s did not represent hugely influential movements of the times. “Conceptualism and Minimalism weren’t on the International’s radar and left a big gap in our ability to do a chronological display of art history,” says Donnan, who was quick to also note a lot of the museum’s gems were acquired out of past Internationals. “Curators have since gone back and filled in the gaps, but often when things were pricier or fewer works were available.”

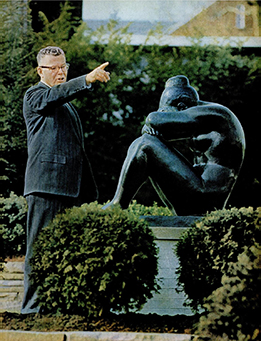

Another Uncrated work, a portrait of self-made Pittsburgh millionaire G. David Thompson, one of the museum’s most generous donors, whispers of another missed opportunity. In the 1933 painting by Washington County-based artist Malcom Parcell, Thompson is seated with what appears to be several paintings by Swiss artist Paul Klee in the background. While the steel magnate gave the museum a generous 80 objects, including some of its blockbuster mid-century works—the Henry Moore sculpture outside of the building’s front entrance, and the prize of its Modernist collection, Willem de Kooning’s Woman VI— the works by Klee hint at what was left on the table. In 1959, following a long relationship with then-museum director Gordon Washburn, Thompson, an unrelenting collector, proposed keeping his one-of-a-kind collection in Pittsburgh through the A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust. But the offer was understood to have impractical conditions attached: By one national magazine account, he required that a new, freestanding building costing upwards of $7 million be erected in his name to house it. Had Thompson’s proposal been given a green light, Carnegie Museum of Art or another Pittsburgh institution could have been home to a collection conservatively estimated to be worth some $350 million today. What was unique about it wasn’t just the numbers of works by Klee and Alberto Giacometti, but the number of those works now showcased in public collections around the world that are considered exemplary examples by the artists. Uncrated will include a number of other fascinating backstories, such as how the Museum of Art’s contemporary art collection includes many works that don’t actually exist until they’re put together for display. Perhaps the most beautiful and well known example: the pair of colorful floor-to-ceiling Sol LeWitt drawings on the wall alongside the staircase leading up to the museum’s second-floor Scaife Galleries. What the museum actually owns is the artist’s idea in the form of detailed instructions and a certification of authentication. Another example: Ann Hamilton’s (offerings), a crowd favorite of the 1991 Carnegie International. The museum acquired only the remnants of the artist’s time-based installation that included 30 live canaries, dozens of cast wax heads, and mounds of melted wax. “I think there’s a lot of value in doing this kind of exhibition,” says Donnan, acknowledging that most people don’t understand what her job as curator—or those of most museum professionals—entails. “It can only enrich your experience of going to see museum exhibitions, to think about how all the works got there, into one room. It will give visitors a sense that there’s a bustling scene behind the scenes.” And so many stories.

Inside the Collection

By the numbers: 29,778 works in Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection (not counting 73,465 photographic negatives in the Teenie Harris Archive) 8,544 prints 6,891 decorative arts 6,648 drawings and watercolors 4,222 photographs 1,361 paintings 364 sculptures 361 film and video 116 architectural models 1,000+ other pieces 2,143 works on view

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Three Rivers Wise · Call of the Wild · I Can Do That · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Stefan Hoffmann · Artistic License: A Wonderful (Still) Life · First Person: Objects of Remembering · Science & Nature: Nights at the Museum · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |