|

||||||||||||

|

Call of the Wild

How Childs Frick, son of Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick, provided the foundation for Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-class collection of African mammals. With seatbelts fastened, staff from Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s mammals section began a long journey—one that would last about seven months, log hundreds of miles, and yet never take them beyond the borders of Allegheny County. Whenever they could find dedicated chunks of time from August 2012 to February of 2013, curator John Wible, collection manager Sue McLaren, and scientific preparator Lisa Miriello would make the trek to and from their offices in the museum’s Edward O’Neil Research Center to a storage location near Pittsburgh. Once there, they would go big-game hunting. Armed with little more than their laptops, the trio took on the task of inventorying the contents of the space, which for decades has served as the final resting place for some 2,000 skulls and skeletons also known as the “big bone collection.”

Think a dedicated section of an airplane hangar and rows and rows of oversized bookshelves with a functioning kind of Dewey Decimal system. Putting your hands on a specific specimen isn’t always foolproof.

After securing competitive federal funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the team’s mission was to confirm the inventory and record the exact location for each specimen. On paper, it seemed like a simple enough undertaking. The reality of the task was another story. “It was hard, tedious work,” Miriello recalls. “We were going up and down ladders and at times dealing with very heavy specimens.” All the while they couldn’t shake the feeling that the project was taking on a life of its own— the life of Childs Frick.

The eldest son of wealthy Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick and Adelaide Howard Childs was the man responsible for bringing back a great deal of new knowledge about both the mammals and birds of East Africa. During his two scientific expeditions to the continent in 1909-1910 and 1911-1912, Frick, then a young biologist, collected and donated some 500 mammals to Carnegie Museums. His finds would eventually become the stars of the Museum of Natural History’s popular Hall of African Wildlife— all the more remarkable considering that Frick’s father and Andrew Carnegie, once wildly successful business partners, had suffered a contentious falling out. Still, Childs remained true to his Pittsburgh roots. After all, it was in the woods near his boyhood home (now Frick Park) where he first started investigating then identifying, tagging, and preserving. His early captures were small, mostly rabbits and raccoons. Born in Pittsburgh in 1883, Frick attended Sterrett School and Shady Side Academy and then went on to Princeton University. After graduating in 1905 but before marrying and settling down, he decided to pursue his first love—and it led him to Africa.

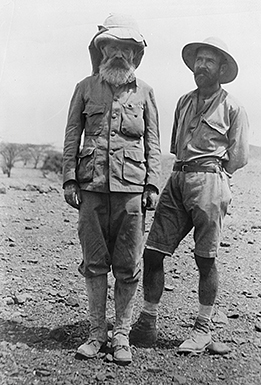

Adventure with a touch of luxuryAfrica wasn’t an unusual destination for 20th-century men of means. It seems the opportunity to conspicuously display wealth (a typical safari would cost $10,000 a month in today’s economy), sportsmanship (aka bragging rights) and generosity (public gifts to public institutions) was a rite of passage. And Africa was chock-full of game, notes McLaren. Of the 5,400 species of mammals scattered throughout the earth, Africa is home to 800, not to mention 57,000 species of plants, 2,000 species of amphibians and reptiles, more than 2,300 species of birds, and a heck of a lot of insects. Perhaps the most prominent conservationist of the time was Teddy Roosevelt. In 1909, the then former president and his son, Kermit, embarked on their own African scientific expedition, giving the rewards—mammals, reptiles, birds, and plants—to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. On the heels of Roosevelt’s journey, Frick and his group, which also included wellrespected ornithologist and naturalist Edgar Mearns, arrived in Djibouti in November 1911 after enduring three weeks at sea.

Dubbed the Abyssinian Expedition, this was Frick’s second and by far the more fruitful and better documented of his two scientific treks to the continent—although his field notes have not been located. Mearns’ journals, however, are part of the Smithsonian Institution Archives, and have proved helpful to Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s project. The expedition is also the subject of a new website (

|

||||||||||||

Three Rivers Wise · Uncrated: The Hidden Lives of Artworks · I Can Do That · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Stefan Hoffmann · Artistic License: A Wonderful (Still) Life · First Person: Objects of Remembering · Science & Nature: Nights at the Museum · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |