|

||||||||||||||||||

Photo: Brad Truxell- DENNIS BATEMAN, CARNEGIE SCIENCE CENTER’S DIRECTOR OF EXHIBITS AND THEATERS |

Three Rivers Wise

They surround us, sustain us, and entertain us. And soon we’ll be learning a whole lot more about Pittsburgh’s famed three rivers in a new Science Center exhibit, appropriately titled H2Oh!. They stretch on for miles, snaking through the city, buoying kayaks and barges, reflecting back fireworks and the lights of the skyline above. Pittsburgh’s three rivers are so integrated into its cityscape that motorists speeding over bridges en route to work or a Steelers game barely ever notice the water around them. And when they do, some would be hard-pressed to say whether the currents alongside them are the Monongahela, Allegheny, or Ohio. What they are, in fact, are complex and fragile ecosystems that provide us with drinking water, recreation, commerce, and animal life. That’s the message behind Carnegie Science Center’s new permanent exhibit, H2Oh!, which helps visitors see these precious natural resources in a whole new light. The Science Center was determined to take full advantage of its spectacular river view, made even more dramatic by a renovation that has opened up new vistas from its River View Café. And in the new first-floor attraction, which overlooks Pittsburgh’s North Shore, visitors can play with a model of the water cycle, carve a virtual watershed out of sand, and touch slithering river dwellers such as the Eastern newt and spotted salamander. Soon, they’ll also be able to simulate a wave on a new outdoor sculpture not far from the bank of the Ohio.

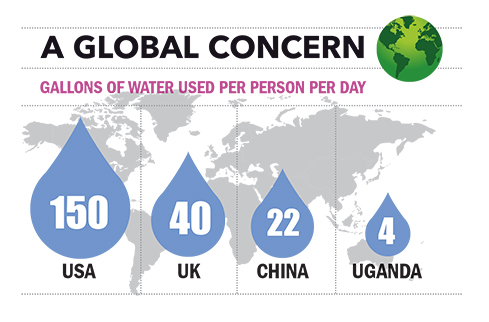

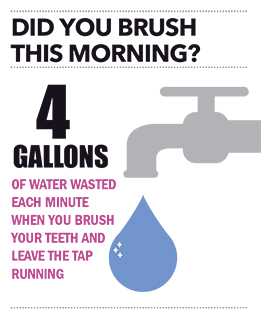

Though Pittsburghers often consider their rivers interchangeable, each has distinct characteristics. Peering out the Science Center’s rear windows, Dennis Bateman, director of exhibits and theaters at the Science Center, points out the confluence just beyond The Point where the Mon (as Pittsburghers call it) and Allegheny join to form the Ohio. He describes the delineation between the clearer, colder Allegheny, which flows from the northern Appalachian Mountains, and the muddier, warmer Mon. “Until the Ohio gets way down past the West End Bridge, it is still two completely different rivers,” he says. “Sometimes there are whitecaps between where the two bodies pass each other.” After checking out this fascinating convergence, visitors can move on to a touch screen that allows them to tap a spot in the river and see—in real time—the pH level, temperature, and other water-quality indicators monitored daily by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. Science buffs will no doubt enjoy exploring how the water temperature changes after a thunderstorm as well as comparing seasonal changes in river conditions. The water cycle taught in fourth-grade science class—the constantly moving and changing states of liquid, vapor, and ice— comes to life as visitors pump liquid into a 3D cloud model and then watch it rain down on land and flow into the rivers and oceans. “It’s a no-holds-barred water table for kids to play in,” Bateman says. “A 5-year-old can splash in there for hours. But it’s also the perfect supplement for an elementary school teacher who wants students to explore the water cycle in action.” Yours, Mine, OursPittsburghers might be tempted to think that in a city famous for its three rivers, there’s no pressing need to conserve water. But the reality is that we should all think twice before taking a half-hour shower or running the water while brushing our teeth. “There is so much less freshwater than people think,” Bateman asserts. At the entrance of H2Oh!, that point is illustrated by a giant chandelier made up not of candelabras but water containers. Forty-four gallon-sized buckets represent the earth’s ocean water, three quart-sized cans represent the glacier ice, and six pint-sized cans symbolize ground water. A much smaller amount—a mere three-fourths of a teaspoon—represents Earth’s river water. It’s a sobering realization that while 71 percent of Earth’s surface is covered in water, most of it is salty and undrinkable.

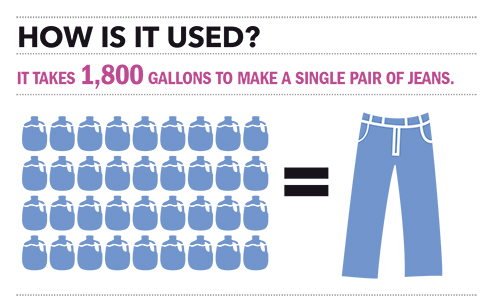

“It takes incredible effort and energy to make the water clean enough to drink,” said Jeanne M. VanBriesen, the Duquesne Light Company Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and the school’s director of the Center for Water Quality in Urban Environmental Systems. “It’s a water footprint— how much energy do I use to make my water clean? We have abundant water in Pittsburgh. There’s a broader question about sustainability.” The cost of cleaning water will soon become top of mind for taxpayers as the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCOSAN) strives to implement a federal order to eliminate all illegal sewer overflow into the rivers by 2026. As in other older American cities, many Pittsburgh area sewers are combined. That means waste from bathrooms, homes, businesses, and industry flows into the same pipes as rain running off roofs and streets. In some spots, it takes only a tiny bit of rain for those pipes to get so full that they overflow. Allegheny County submitted a $2 billion wet-weather plan to comply with the order. “It’s a multi-billiondollar project that’s going to affect many taxpayers who come to the Science Center,” Bateman says. “So the more we can get them to understand it, the better-informed voters they will be.” The process of cleaning water is illustrated graphically—and a bit grossly—within the exhibit’s “dirty water fountain.” A murky tube of river water is mounted on the wall, adjacent to the public drinking fountain. When visitors take a drink, air bubbles up from the fountain’s water supply, making them think twice about the process required to take the river water—literally right outside the Science Center’s doors—and make it suitable for their consumption. Nearby signage assures them the fountain water is clean and fresh, and shows the process that makes that happen. Yet another reason to conserve water is the amount of it required to make other products. When you factor in the growing, cleaning, and cooking of the potatoes, it takes 62.5 gallons of water to make one bag of potato chips. A gallon of water goes into making a single 12-oz. bottle of water. Water quality and conservation is a unifying concern for the region. The Science Center drives this fact home in a digital map that tracks water from a single rainfall as it flows from the Laurel Highlands to Pittsburgh. “We want to show people connectivity. What you do in the city affects the water elsewhere,” says John Wenzel, director of Powdermill Nature Reserve, the ecological field station of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, one of the numerous local partners informing the exhibit, including experts from CMU, Pitt, and river-focused organizations 3 Rivers Wet Weather and The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

“Humans have this natural inclination that if they are not experiencing something it’s not important,” Wenzel says. “They think the headwaters in the Laurel Highlands are not important to the people in Pittsburgh, and if they dump their trash it will go away. But that’s not a responsible way to lead your life. You have to make decisions based on the connectedness of all of us.” It’s precisely that connectedness that drew the Colcom Foundation to support the development of H2Oh! “The quality of our region’s water is directly related to quality of life,” says Carol Zagrocki, program director for the Colcom Foundation, noting that the Science Center’s riverfront location and reputation as a seasoned educator is a win for the community. “The Science Center brings science to life for children and adults. It’s well-suited to explain how our daily decisions can impact natural resources. Awareness of these impacts will hopefully encourage a new generation of responsible stewards of our environment.” Citizen ScienceAs the steel mills closed and government cracked down on industrial polluters, the water quality of the rivers has improved markedly—to the point where a fisherman can sometimes reel in an 11-pound bass. “Fifteen years ago, if you told someone there would be a bass fishing contest in Pittsburgh, they would have laughed you out of the room,” Bateman says. “But the rivers are a barometer of the health of the region. As they get healthier, they create opportunities for jobs and recreation that benefit the economy and revitalize our natural environment.”

Many Pittsburghers might be surprised to learn that the waterways are home to such river dwellers as darters, killifish, dace, and the ever-popular brook trout. If they watch carefully, they might also catch a glimpse of the bullfrog, American toad, and the Eastern box turtle along the riverbanks. To facilitate these introductions, H2Oh! invites the curious to peer at these critters through a magnifying glass, and, guided by staff, even to touch them. Some of these animals are ‘rescues’ who come to the Science Center from regional wildlife refuges. “We want to show connectivity. What you do in the city affects the water elsewhere.”

- JOHN WENZEL, DIRECTOR OF POWDERMILL NATURE RESERVE

Wenzel notes that razing forests for housing developments also leads to increased use of chemicals, as residents strive to keep their lawns pristine. “Homeowners use fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides 10 times more per acre than a farmer does,” he says. “That just poisons our streams.” Cities like Pittsburgh are implementing more “green” solutions to water runoff. “Some of the problems that exist are the result of the decisions we make about building,” VanBriesen adds. “We can fix them with urban green infrastructure—green roofs, storm water retention areas, rain barrels. This will hold the water back so it doesn’t flow into the pipes so quickly.” Most people can only guess at the water quality of a river by eyeballing its color or sediment. But H2Oh! gives citizen scientists a better way of gauging river health through the identification of aquatic insects. For example, stoneflies are an indicator of purity because they can’t survive in warm, oxygen-depleted water. On the other hand, black flies thrive in the murkiest of currents. By consulting the interactive website macroinvertebrates.org, a joint project of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pitt, and CMU, visitors can identify tiny creatures in amazing detail with the help of gigapixel image technology. A stonefly, visitors learn, can be identified by its two tails and lack of abdominal gills. The current site includes 12 insects, though Wenzel hopes to expand it to include 50.

Exhibit organizers hope that H2Oh! gets visitors excited about the water right in front of them—and motivates them to make decisions that conserve all freshwater resources. “People don’t usually protect and care about things they don’t understand or recognize,” says Wenzel.

And what better way to get the public to understand and appreciate water quality: Introduce them to the microbes (microscopic bacteria) living in their home tap water. An interactive map in the new exhibit allows visitors to point to an area of the city and see which microbes have been found in the water supply there. And don’t worry—not all microbes are bad. This map is updated by way of the Pittsburgh Drinking Water Microbiome Project, which is fed samples by middle school students from across the city who collect in their own homes. The results are analyzed through DNA testing at the University of Pittsburgh.

With approximately 700 million people on Earth still lacking access to clean drinking water, studying microbes can help spur interest in water treatment around the world. It also gets kids interested in what they drink every day. “We hope that this will be the largest map of microbial ecology of drinking water ever made,” Bibby says. “It’s opening up middle school students’ eyes to microbes and making them think about water quality. It makes people confront the science of it.” The same could be said of the rest of H2Oh!, which, simply put, drives home why our rivers matter. “Virtually everyone in our area lives within walking distance of a ‘crick’ or stream or river,” Bateman says. “If we can get them interested in their own backyard based on what they see in this exhibit, they’ll understand and care more about this essential natural resource.” H2Oh! is presented by the Colcom Foundation and made possible by additional support from The Fisher Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, the Laurel Foundation, Dollar Bank, and Peoples.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Call of the Wild · Uncrated: The Hidden Lives of Artworks · I Can Do That · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Stefan Hoffmann · Artistic License: A Wonderful (Still) Life · First Person: Objects of Remembering · Science & Nature: Nights at the Museum · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |