|

||||||||||

|

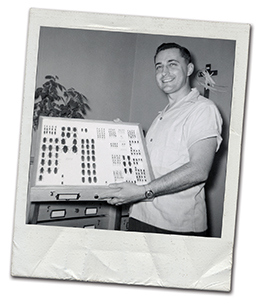

A sampling of Bob Surdick’s collection on display at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. |

For the love of bugs

A childhood trip to the Museum of Natural History ignited an enduring passion that eventually led to a gift of a lifetime. In 1936, Robert Surdick hopped a trolley from his home in Carrick to Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Oakland to see its world-famous bug collections. The young nature lover, just 13 years old, soaked in the beauty of the museum’s meticulously mounted specimens and left utterly smitten.

His boyhood obsession, fueled in part by dozens of return trips to those same collections, only deepened over the next 70 years. After working all day as a production manager for a local advertising agency, Surdick would hunker down in his basement workshop, sometimes until 3 a.m., mounting wings and spindly legs. He planned the location and timing of family vacations around bug collecting and would pull his car off the road— anytime, anyplace—to capture an interesting insect buzzing past the headlights. He collected and collected until he amassed 90,728 specimens, including 15,270 moths and butterflies, each carefully identified and filed into 256 insect drawers and 16 custom wooden cabinets he built in the basement of his longtime Bethel Park house. In all, his hobby covered 589 square feet of living space and consumed countless hours. At age 88, and only after being diagnosed with a brain tumor, Surdick finally put down his collector’s net. He told his son Larry that he wanted to donate his collection to Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the institution that ignited his fervor so many years earlier. In the summer of 2012, when Larry told his father that his vast collection of bugs had been transferred via truck to the museum, his father cried. “At least I know where my babies are now,” he said. He passed away weeks later on July 27, 2012.

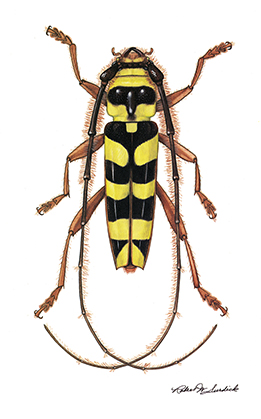

When Larry saw the straight rows of meticulously-pinned longhorn beetles, his dad’s favorite insect, he teared up. “I was so impressed to see them in the museum,” he said. “Seeing those insects again, it brought it all back.” John Rawlins, curator and chair of the section of invertebrate zoology and interim co-director of the museum, says the gift from the “citizen bug collector” is one of the most remarkable donations ever received by the museum. It contains some rare finds, such as snakeflies (Rhaphidioptera), zorapterans (Zoraptera), and web-spinners (Embioptera), but the real power of the collection, he notes, “is that so many species are from our own backyard over many decades.” Most of the bugs were collected in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Maryland, but a good number hail from as far away as Arizona, Colorado, Florida, and even Brazil (Surdick traded for those). While local fields are filled with amateur and professional entomologists, some of the insects in the Surdick collection represent the first of their kind collected in Pennsylvania, filling in important gaps in the museum’s vast database.

Visitors are impressed, says Rawlins, at the size of the underwing moths, dragonflies, damselflies, and beetles that Surdick collected in his own community of Bethel Park, parts of Greene County, and other nearby destinations. “Where do they come from?” they frequently ask him. And the answer— “from your backyard”—he says generally surprises them. “The remarkable thing is Surdick’s fascination with longhorn beetles,” says Rawlins. Several drawers showcase their spectacular diversity of shape, size, and color. The longhorns are a group of insects that Surdick, also a talented painter, loved to draw. What’s even more remarkable, Rawlins notes, is the pristine condition of Surdick’s collection. “It was flawlessly prepared and labeled by a self-taught scientist who was nothing short of meticulous about everything he did. It’s almost like an art form,” says Rawlins, “crafting the position of the bug legs like a sculpture.” TRUE BUG LOVERawlins has watched it happen many times. First an enthusiast collects one butterfly and then another, and before he knows it he’s planning vacations around the time when monarchs fly over a particular mountain. He loses control, always chasing the next moth or beetle in a world filled with a dizzying variety of bugs. “True bug love is like an infectious disease,” he says.

Surdick’s daughter, Rebecca Surdick Pifer of White Post, Virginia, followed in his footsteps, becoming a professional entomologist who published papers on stoneflies. Larry, who runs his own water filtration business, never shared his dad’s fascination, but he looks back fondly on many father-son insect expeditions. One evening at about 11 p.m., on the ride home from Erie to the South Hills of Pittsburgh, young Larry watched as his father pulled off the road. An io moth marked with eyelike spots on its hind wings had fluttered past the headlights. Surdick yanked his net out of the car and pursued it. “It didn’t matter where you were and what time it was, it was always time for bugs,” Larry recalls. Larry spent many a night helping his father spread trees with a mixture of fermented rotten fruit that attracted insects. Vacations were never trips to the beach, but rather bug-collecting jaunts—sometimes to Greene County but also to West Virginia, the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Utah, and Florida. Wherever they journeyed, they could never go away for more than a week or two. “He always had to go home to his babies,” says Larry’s wife, Kay Surdick. Her father-inlaw would rush home to make sure there were enough moth balls in his insect drawers to keep the vermin away. Larry also recalls the times he would come home from school and his mother would tell him to stay out of the kitchen because his father was baking cyanide-laced pots in the oven; and the time he was bitten by a rattlesnake on a family collecting expedition in the Shenandoah Valley. CITIZEN SCIENCEThough bugs were his passion, Surdick earned his living as a production manager for BBD&O advertising agency in Pittsburgh. A pragmatist, he didn’t think he could support his family as an entomologist. He was well-respected in his profession, but that never decreased his lust for his hobby. He would leave work promptly at 5 p.m., take the trolley home, eat dinner, spend some time with his wife, Tressa, and the kids, and then head down to his bug room until the wee hours of the morning. He might have caught five hours of sleep a night, recalls Larry, who can’t remember a single day when his father wasn’t working on bugs, whether it be mounting them, reading about them, or planning a trip to collect them. Surdick was a former Air Force gunner —during World War II he flew 26 missions over Germany—and the discipline he learned in the military stuck with him. “An insect collection can tell you a lot about someone’s life,” says Larry. “He was meticulous and neat, in his home and his collection. He was very firm. He was a real Type A personality. Everything has to fit or it doesn’t work.” Yet for all his entomological accomplishments, Surdick was never one to boast. “He didn’t want an attaboy for any of it,” Larry says. “True bug love is like an infectious disease.”

- John Rawlins, curator and chair of Invertebrate ZoologyRawlins, who met Surdick three months before he died to look at his collection and discuss the donation, found him refreshingly down-to-earth. “Sometimes nature lovers show off,” says Rawlins. “They turn bird watching or insect collecting into a competitive sport. It ruins it. He was very turned off by that. He was straightforward and direct.” Surdick’s retirement at age 62 freed him up for even more bug collecting. As he aged, the slim man stayed fit in order to be able to go on his many field expeditions, always accompanied by Tressa. “She was his support staff,” says Larry. Then, in 2005, Surdick was diagnosed with macular degeneration, and his failing vision threatened the hobby he loved. He would fight off the disease with no fewer than 75 injections in his left eye and 40 in his right eye. He never went blind, and with the aid of a magnifying glass, he worked on his beloved collection until the very end. In May 2012, Robert and Tressa moved to Rochester, N.Y., to be near Larry and his family, leaving his babies behind at the museum that sparked his love for them. Rawlins is thrilled about Surdick’s lifetime obsession and enduring legacy. “What we have are 100,000 bugs and 100,000 bug stories, all waiting to be told,” he says. And even though Surdick’s “babies” represent only one percent of the museum’s massive inventory of insects, they still add great value to the museum’s collections. Carefully labeled and pinned, the Surdick collection provides clues on how environmental changes have caused shifts in insect biodiversity over the past five-plus decades. “It’s the biggest issue mankind is going to face in the next century—how to cope with the impact of environmental changes,” Rawlins says. “It will be critical to get a handle on environmental changes and to understand conditions that influence the well-being of plants and animals. The presence or absence of certain bug species is critical information as to the ‘health’ of the natural ecosystem so necessary for sustaining life.” Surdick’s collecting efforts became serious citizen science, with lasting, real-world value, says Rawlins. “It’s almost like Bob Surdick knew he was running a lifelong sampling experiment.”

|

|||||||||

What's Your Energy IQ? · A Playful, Soulful Spectacle · Energy in Human Form · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Donald Warhola · Artistic License: Girl Power · Field Trip: Pop goes China · About Town: Art for All · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |