Winter 2013

Winter 2013|

“I’ve seen a lot of Andy exhibits, but this time I saw something new. I came away feeling a little like Alice

in Wonderland falling into this different world. I think the Chinese are eager to be a part of that world.” - Warhol friend and photographer Christopher Makos |

Pop goes china

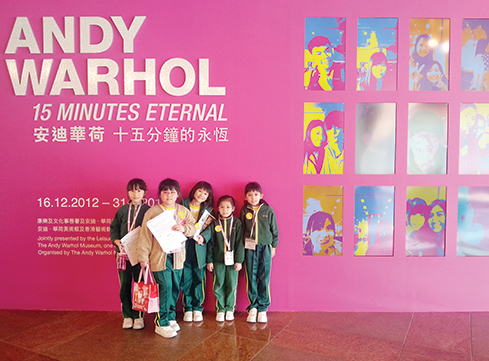

The Warhol takes Andy back to China to inspire a new generation of art makers. Last spring, as a means of commemorating the 25th anniversary of Andy Warhol’s death, The Andy Warhol Museum unveiled the traveling exhibition Andy Warhol: 15 Minutes Eternal in Singapore, the start of what would be a 26-month, fivecity tour of Asia. Featuring such megahits as Jackie, Marilyn, Campbell’s Soup, and Liz, the tour made stops in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Beijing before setting out for its final destination: Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum.

Sponsored by BNY Mellon, it’s the largest compilation of Warhol’s work to trek across the Pacific, featuring more than 300 paintings, photographs, screen prints, drawings, and sculptures. Joining some of Warhol’s most famous portraits is work from the artist’s largest and most comprehensive series, The Last Supper, and his iconic Self- Portrait, as well as a rich educational component that local teachers could use to help bring Warhol to the younger masses. “Our sole raison d’être is to promote Andy Warhol’s legacy not only in Pittsburgh and the United States but throughout the world,” says Warhol director Eric Shiner. “We’re doing just that by sharing our collection, our knowledge, and our scholarship.” Enter Nicole Dezelon, The Warhol’s associate curator of education. Navigating her way through the language and cultural terrain, not to mention logistical speed bumps, Dezelon and her team have lead VIP and public tours, taught local museum staff how to silkscreen (so they can, in turn, host workshops), and identified school partnerships for projects like an international time capsule swap. “The hook Andy has with students is that they love to talk about music, art, and pop culture,” says Dezelon. “It’s all current.” Warhol’s appeal to China’s contemporary artists, Shiner notes, has more to do with the stories he tells in his art. Two artists in particular have been listening for decades. Back in the early 1980s, Ai Weiwei (pronounced eye way-way) and Xu Bing left China as political exiles and sought refuge in New York City. While other expats of the time moved to Paris or Berlin, Ai and Xu chose their destination, in no small way, to literally follow in Warhol’s footsteps. Although they never came face to face with the man and have since returned to China, neither one has forsaken his fascination with the pop-culture icon. “By seeking to democratize society through the democratization of art,” Shiner says, “Ai is embracing a very Warhol-like model.” The shared sensibilities don’t stop there. Ai employs a variety of mediums, including film, photography, sculpture, and sweeping installations to explore the power of multiples, repetition, consumerism, and power. Nowadays, the 56-year-old continues to make news—both as the subject of government scrutiny and as someone who encourages scrutiny of the government. With his politics and art so intertwined, Ai is nearly as well known to Westerners as his own Beijing neighbors. Xu’s role as vice president of China’s Central Academy of Fine Arts, which hosted 15 Minutes Eternal in Beijing, also affords him recognition and prominence. Noted for his print making, calligraphy, and large-scale installations, the 58-year-old Xu also works with multiples and repetition. He creates arrangements, sequences, and series of what appear to be Chinese characters but are in fact the products of his own invented language. “His work is designed to challenge and change perceptions,” Shiner says. In a 2007 interview with Brooklyn Rail, Xu professed that “Andy Warhol learned a lot from Mao Tse Tung. Compare Mao’s pop culture to Andy Warhol’s pop culture,” he said. “If you had the experience of the Cultural Revolution in China you can understand authentic pop culture. Everybody had to read the same book and do the same thing. If you look at the Andy Warhol photo where he is standing in front of big portrait of Mao in Tiananmen Square, then you can understand how Andy Warhol’s art works with Mao’s ideas about the masses, the people, and pop culture.” Despite these strong influences on Chinese artists, the average Chinese citizen had yet to be formally introduced to the King of Pop art, until now. That’s not to say Warhol’s works—particularly his celebrity portraits—aren’t familiar. It’s just that the artist behind them had long remained an unknown entity to most Chinese. Warhol would probably appreciate that fact. During his one and only trip to mainland China in 1982, his friend and photographer Christopher Makos, who accompanied him, recalls that Warhol enjoyed the anonymity. Not surprisingly, he also felt a kinship to the uniformity—most evident in the unflattering Mao suits—that prevailed. As tourists, Warhol and Makos visited the Great Wall, Tiananmen Square and, of course, posed in front of the famous Mao portrait. Warhol and Mao did share a unique history. In 1972, as the chairman prepared for President Richard Nixon’s landmark visit, Mao was headline news. For Warhol, that translated to a celebrity status rivaling Elizabeth Taylor’s or Jackie O’s. So Mao got the Warhol star treatment, perhaps to his subject’s and his subject’s subjects’ chagrin. “Warhol used an incredibly bright color palette for the Mao portraits, and in some cases put lipstick on him,” Shiner says. “But he wasn’t making fun of Mao or turning him into a drag queen.” Still, old feelings and misperceptions die hard. As a result, the portraits were a no-show in Shanghai and Beijing. “In an ideal world,” Shiner says, “I would have loved to have seen them there. But we had to be very aware of social mores. We didn’t want to put anyone’s job at risk. “I know it will happen one day,” he adds. “We’re just starting the conversation.” To Makos, the conversation surrounding 15 Minutes Eternal was spectacular. “I’ve seen a lot of Andy exhibits, but this time I saw something new. I came away feeling a little like Alice in Wonderland falling into this different world. I think the Chinese are eager to be a part of that world.” According to Shiner, “So much of China’s perception of the United States is based on consumer culture, brands, and lifestyle. But it’s a very surface understanding. Andy looked at what lies beneath.” To date, the show has been well received and Warhol is once again a media sensation, even breaking attendance records at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai. “It’s always going on with Andy,” says Makos. “He’s completely present to me and I think the Chinese are eager to be a part of the scene because they couldn’t participate at the time. There is such a deep well of curiosity there.”

|

What's Your Energy IQ? · A Playful, Soulful Spectacle · Energy in Human Form · For the Love of Bugs · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Donald Warhola · Artistic License: Girl Power · About Town: Art for All · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |