|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A playful, soulful spectacle

With works by 35 artists from 19 countries, the 2013 Carnegie International bursts out of, and into, Carnegie Museum of Art. Daniel Baumann, one of the three curators of the 2013 Carnegie International, knew TIP was a success back in September, when British artist Phyllida Barlow and her small team of assistants were still putting the finishing touches on the towering, nest-like sculpture that appears to be spilling out of (or into, depending on your perspective) the front entrance of Carnegie Museum of Art. It was a typical bustling weekday in front of the Oakland museum when an inline skater weaved her way along the sidewalk— all the while rubbernecking, her eyes glued to the soaring structure. Baumann recalls how she sped by, her body moving forward as her head cocked sideways, and said, simply, “Whoooooooooooa!” “It’s beautiful, but it’s also menacing,” says Baumann about the jungle-like sculpture that, thanks to its sheer size and location, headlines the exhibition. Baumann and team asked Barlow to create something that could help “give order” to the front of the museum, a location he viewed— pre-Lozziwurm playground—as a bit messy, disconnected, and cold. “She said the syntax of the space is so chaotic—between the traffic, the fountain, the sculptures—she didn’t think it made sense to try and order it,” Baumann says. “Instead, she told us, ‘I want to add another layer on top of it so that this visual mess almost implodes.’” That this year’s International opens with an installation that embraces the messiness of everyday life is fitting for a show that challenges the way we read history, stands up for bold dissent, and celebrates both the beautiful and the menacing—all the while, as with Barlow’s “anti-monumental” sculpture, not taking itself too seriously. One word used repeatedly to describe the exhibition of works by 35 artists from 19 countries is thoughtful— in regional reviews as well as in glowing critiques from The New York Times and The New Yorker. Feedback of all kinds points to the remarkable partnership of Baumann, Dan Byers, and Tina Kukielski, the show’s curators. “The more time I spent [with the exhibition]… the more I envied the people of the Steel City, who get to have it at their doorstep for the next five months,” wrote Andrew Russeth of the New York Observer. In the words of Baumann, “Come linger, get inspired, and play with it.” A FANTASTICAL JOURNEY

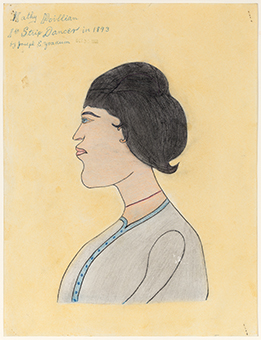

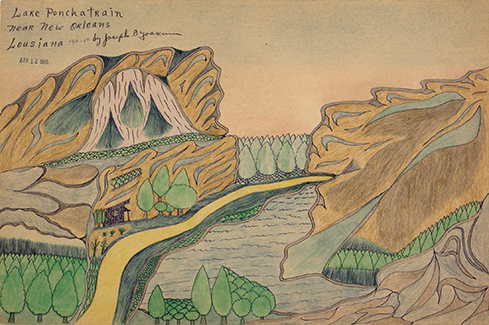

Having claimed to crisscross the globe “four times over” during the 1910s and ‘20s as a circus advance man, soldier, hobo, and even stowaway, the Missouri native who died in 1972 said he drew from a deep well of memories made decades earlier in places as far away as Asia and Australia. While experts say it seems unlikely that he traveled to all the places he said he did, and that many of his drawings bare a resemblance to National Geographic photography from the early 20th century, that’s really beside the point. The gifted storyteller spun magical, intricate tales through his landscapes—and, like his life, they were littered with both fact and fantasy —winning him a devoted following of artists, including the Chicago Imagists who amassed some of the most significant collections of his work (one of them, Jim Nutt, loaned work for this show). “Most people think all the art they see in institutions is done by professionals and that they make it for a very specific market, but that’s not true,” says co-curator Daniel Baumann. “Art happens in places we don’t expect it.” The group of 57 drawings on view in the Heinz Galleries—the vast majority of which are landscapes with a few portraits sprinkled in—is the largest exhibition of Yoakum’s work in decades. For the curators, it was a way to infuse the true sense of discovery that comes with travel— real or imagined.

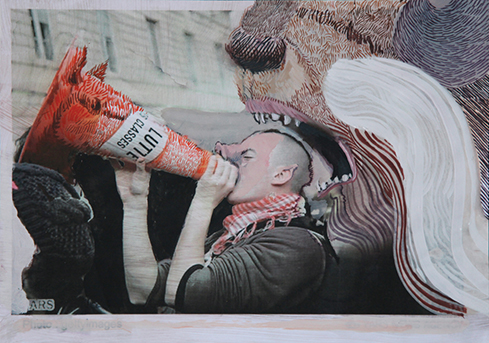

“It was really important to us to bring a sense of distance into a show that’s about the global,” says co-curator Dan Byers. THE ROLE OF SPECTATORKnown primarily as a painter, Iranian artist Rokni Haerizadeh studied art and literature in his native Tehran before he and his brother, Ramin, also an artist, fled to Dubai in 2009 after their work was seized from a private collection in Tehran. Rokni’s latest body of work, making its U.S. museum premiere at the 2013 Carnegie International, uses animation to investigate what the artist has declared iconic moments of our time. “The work really struck me over the head,” says co-curator Tina Kukielski. “Rotoscope animations are a very rudimentary way of making an animation in today’s digital world.”

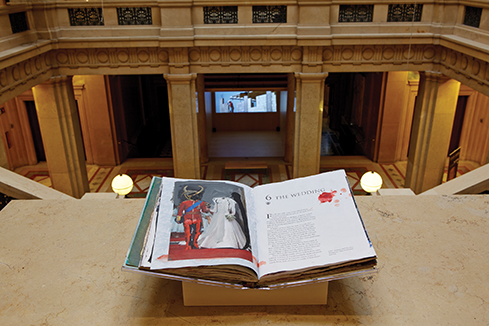

For each of his animations, Haerizadeh painstakingly handpaints and draws over thousands of appropriated video stills found online. In Just What Is It that Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, he transforms media imagery of protest, disaster, and violence from the 2009 Iranian demonstrations into strangely beautiful yet disturbing parables—where human heads of protestors and newscasters alike are replaced with those of animals, highlighting man’s basic instincts. Reign of Winter, shown for the first time at the International, takes aim at the latest British royal wedding. It’s how the media presents the pomp and circumstance—and the spectator role played by its consumer—that interests Haerizadeh most.

A selection of his drawings, along with a sketchbook that visitors may flip through, are on view along with his silent animations in a setting known for its own ritual and formalness: the museum’s ceremonial entrance, the Grand Staircase. ART AS HEALING

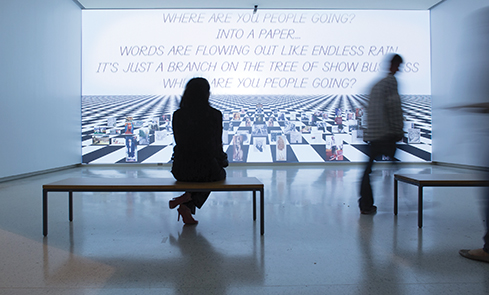

A factory worker for most of her life, Guo began drawing at home in her mid-40s as a way to deal with pain and illness, employing I Ching and Qigong, a practice rooted in philosophy, martial arts, and medicine that combines breath, movement, and meditation to achieve balance and calm. Soon afterward, her neighbors began requesting drawings for their sick relatives. Guo’s stunning, calligraphic, and somewhat obsessive line drawings appear to trace the inner movements of their subjects’ thoughts, energy, and blood. “We were attracted to them because they’re hauntingly beautiful images,” says Byers. “But we’re also interested in artworks that have a double or triple function—that have an impact on the world beyond its situation in the gallery.” The 10 line drawings—the largest display of Guo’s work to be shown in the United States —acted as healing drawings. “They were tools or mediums through which the body’s energy and health was distributed,” says Byers. “They’re also beautiful landscapes of the mind, and landscapes of the body, both specific and abstract.” PAYING ATTENTION IS FREELos Angeles-based artist Frances Stark’s latest video installation, Bobby Jesus’s Alma Mater b/w Reading the Book of David and/or Paying Attention Is Free, is an intriguing mash-up of poetry, West Coast rap, and art history. Continuing Stark’s self-proclaimed “brazen pursuit of unlikely alliances,” it’s set to the music of Compton rapper DJ Quik and combines collaged images applied directly to the gallery wall with projected text culled from conversations with a guy she’s nicknamed Bobby Jesus. He’s a South Central College student and self-described resident of “planet ’hood” who has become Stark’s studio apprentice and friend. The presentation can be overwhelming at first, says Baumann, but it’s also an incredibly stimulating experience. “Your brain is challenged by what you hear, what you see, and trying to make sense of it,” he says. “You need to watch it more than once to have it, and then you realize it talks about very political things and very private things.”

And sometimes uncomfortable things. Everything in Stark’s life— especially language—is fair game in her art, which only recently evolved from collages, drawings, and magazine spreads that look mostly inward, to videos and audio installations that boldly encounter the other—from Internet chat rooms to young black rappers. This kind of investigation, says the artist, is how she stays in touch with herself, and the world. Stark has said, “Art is a kind of faith, it’s a faith in paying attention. And that is free, period.” BODY LANGUAGEThe 2013 Carnegie International marks the first time San Franciscobased sculptor Vincent Fecteau has combined works from different series. The mini-survey of sculptures from the last seven years, all crafted from papier-mâché, “call out to me hips and shoulders and elbows and the kind of awkward positions that bodies can be put into,” says Byers, noting that the artist talks about the sculptures as trying to physically articulate an abstract feeling, such as a gesture, mood, or the space between hearing a song and being able to express it. Fecteau, a former high-end floral designer, only creates four to seven works a year, as he uses a labor-intensive process of addition and subtraction. “He builds up layers and then carves them away,” says Byers. “The works become a conflation of a painting and a sculpture, where sometimes the painted surfaces follow the contours of the sculpture or oftentimes define various characteristics, almost going against the way the sculptures are working.”

Interesting to note is that the artist made his wall-mounted works reversible—“360-degree sculptures” as Fecteau calls them. They hang on a peg so that during the run of the exhibition they can be reversed and maybe even rotated. Fecteau is particularly thrilled, says Byers, that his work is being displayed near Paulina Olowska’s paintings that are based on postcards featuring Polish home-knitting patterns from the 1980s—a kind of Western high fashion meets thrifty Eastern Europe. “When he saw the paintings—of gesture, highly specific cloths, and a certain kind of taste—he said, I think with a bit of humor, ‘That’s exactly the kind of thing I’m thinking about when I make my work.’” TO HOMESTEAD WITH LOVE

“I’m using the images as metaphors,” Strauss says. “It’s about the shifting structure of the community, and people not only being able to talk about their own image, but having their own image placed within the museum, which matters a great deal because of the history of Carnegie and Homestead.” Homestead was, of course, once home to Andrew Carnegie’s flagship plant, Homestead Steel Works, and the site of the infamous 1892 labor strike. Strauss believes the struggling neighborhood is “key to how we think about cities, living and dying.” So she set out to capture the faces that make up the close-knit community, allowing her subjects—the individuals whose lives have largely been shaped by the success and failure of the former steel mill—to have a say in how they want to be seen. Strauss says she became interested in Homestead and how it’s moving forward because “it’s a place that contributed to all of our lives in ways we don’t necessarily see.” Like the work of fellow International artists Zanele Muholi of South Africa and Pedro Reyes of Mexico, Strauss’ art has a double function that reaches far outside the museum walls. “Zoe’s work is really a record of Homestead today and a way for her—and all of us, really—to explore the labor history of Homestead,” says Byers. A PLAYDATE WITH ARCHITECTURE

“They say children at the school are eight times more active than Japanese children on average,” says Baumann. “So in a very natural way, the building keeps the kids moving, and we know what a big challenge that is nowadays.” For their contribution to the International as part of The Playground Project, Tezuka Architects transport museum-goers to the suburbs of Tokyo by way of giant projections to witness 5- and 6-year-olds play their way through the one-story, oval Fuji Kindergarten building that’s ingeniously fitted with a flat roof accessible from both open stairs and ladders that pop up through its skylights. This turns a not-so-ordinary roof into a deck, running track, and playground all in one. To add to the fun, the children can slide back down into the building’s courtyard using—what else?—a shiny metal slide. “So in a very natural way, the [Fuji Kindergarten] building keeps the kids moving, and we know what a big challenge that is nowadays.”

- Daniel Baumann, co-curator, 2013 Carnegie International

And keeping with the theme of their innovative project, the architects have added a soft floor and plenty of balloons to their Heinz Architectural Center installation, encouraging visitors to not only look and listen, but to interact as they learn, ponder, and, of course, play.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

What's Your Energy IQ? · Energy in Human Form · For the Love of Bugs · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Donald Warhola · Artistic License: Girl Power · Field Trip: Pop goes China · About Town: Art for All · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |