|

|||||||

|

Photos: Olivier Chavasseau

|

Tracking the Origins of Humans

As a young scientist, Chris Beard turned paleontology on its head with his compelling new vision of primate evolution, which places our earliest ancestors in Asia, not Africa. Today, his quest to unearth our evolutionary roots thunders on. One day last October, Chris Beard found himself in a Land Rover racing across the Sahara Desert at 70 mph. He had risen at 4 a.m. in the southwestern Libyan city of Sabha to ride all day across the trackless desert. Beard’s destination was a research outpost 150 miles from Libya’s southern border with Chad. In a way, he was headed to our deep past—39 million years ago, to be exact. Ahead of him lay two and a half weeks of dawn-to-dusk work, much of it involving picks, shovels, and piles of mud. Hardly a day at the beach, but for Beard, a fossil hunter and paleontologist, this was “paradise.”

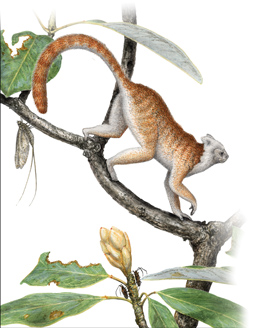

A square-jawed, compact man with a boyish face and the easy and succinct manner of a teacher, Beard has spent much of his career hunting for fossils of the earliest anthropoids, the ancestors of monkeys, apes, and humans. For years, scientists believed these ancient primates originated in Africa. This made sense since the human lineage originated there 5 to 7 million years ago and modern humans came “out of Africa” about 100,000 years ago. But Beard’s work has shown that the oldest anthropoids—squirrel-sized mammals that lived in the treetops—probably evolved in Asia. “For me it was a kind of eureka moment,” says Beard. “When we first started working in China, we certainly didn’t expect to find early anthropoids there, but once we were able to compare our fossils with early anthropoids from Africa, it was very clear what we had.”

But Beard isn’t finished trying to rewrite the story of anthropoid evolution. After establishing the Asian origin theory, he joined an international team of scientists in the Libyan desert to trace the steps of the anthropoids as they came into North Africa some 39 million years ago. Rewriting the rulebookLast October’s visit was a long time coming. Beard tried unsuccessfully for several years to attain a visa to Libya for fieldwork, the bread-and-butter of his research. International politics, as Beard learned long ago, bleeds into science, oftentimes playing an unavoidable role in where and when scientists can conduct digs. But with help from his Libyan and French colleagues, last fall Beard finally scored his Libyan papers, becoming one of the first American scientists since the 1960s to gain working access to the North African country.Like most dig sites, Dur At-Talah is raw and unforgiving. The sun blazes during the day, when temperatures can reach 115 degrees. At night, temperatures can drop near freezing. Sandstorms push heaps of sand through the screened-in air flaps of the scientists’ tents at night. The team has to bring in all its own water to the site, which makes cleaning and sifting chunks of excavated earth an extra chore because they must re-use every drop of water. Oh, and the desert bugs really like to bite.

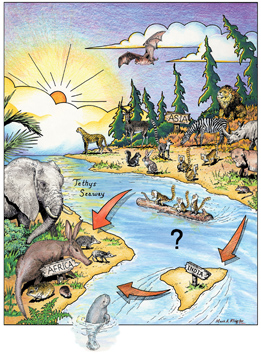

In a recent issue of Nature, Beard and his collaborators identified three new families of anthropoids previously excavated at Dur At-Talah. “We found a diversity of these anthropoids all living together and shockingly old,” says Beard. “That rewrites the rulebook, because nobody had any inkling that at that time you’d have that diversity of anthropoids in Africa.” He thinks these animals may have come in waves to colonize Africa, or that several species of anthropoids came to North Africa at roughly the same time. “Getting into Africa was probably at least as important as getting out of Africa,” Beard notes. For millions of years, Africa had been an island continent, much like Australia is now. None of the ancestors of today’s iconic African megafauna—lions, cheetahs, giraffes, rhinos—originated on the continent. They were all Asian imports. The animals that did live in Africa—early forms of aardvarks and hedgehog-like hyraxes, for example—were poorly adapted to compete with the mammals of Asia and Europe. “We believe when these first anthropoids got into Africa it was almost as if they’d won the lottery,” says Beard. “Suddenly they were on this giant tropical continent, and there was nothing there that competed with them.” This rich new continent, Beard believes, may have been the perfect place for anthropoids to evolve from more primitive, vaguely lemur-like primates into animals that looked more like modern monkeys. Their bodies became better suited to walking on all fours along the tops of branches, their snouts shortened to give them increased vision, and their eyes became surrounded by bony sockets like those of living monkeys, apes, and humans. “We believe when these first anthropoids got into Africa it was almost as if they’d won the lottery.”

– Chris Beard“Each new species became an evolutionary experiment on how best to be an anthropoid,” Beard says. “This starburst of evolution may well be the reason we have the bodies we do—and that anthropoids ultimately took over the planet.” A reputation under fireSam Taylor, director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, says Beard’s recent work in Libya is emblematic of the kind of groundbreaking science he’s been producing since he came to the museum 22 years ago.

In the distance is the team’s remote base camp, comprised of sleeping tents and a tent that doubled as a dining hall and work space, at the foot of Dur At-Talah.

“Chris was in Libya for about a month,” says Taylor. “When he returned, he had specimens and confirmation of ideas he had generated that were so important to him that he immediately knew what direction he wanted to go with them. He literally unpacked his suitcase, came to work the next morning, and by the end of the week had the next proposal drafted for new research. Most of us would have still been jetlagged.” Beard has long known he wanted to study our earliest ancestors, but it took him a while to figure out just how far back on the family tree he wanted to look. As a graduate student, he considered studying early humans. But the field was overcrowded. “There were 20 aspiring experts for every human fossil,” Beard recalls. With early primates, the ratio was reversed, he notes. “There were lots of fossils and not a lot of people studying them.” Beard immediately made a name for himself by challenging conventional wisdom in his field. In the early ‘90s, he discovered Eosimias with a team of researchers in China. It was a much older and far more primitive primate than the African animals then thought to be the earliest anthropoids. A freshly minted Ph.D., Beard was already turning the world of primate paleontology on its head by asserting that Asia, not Africa, was the birthplace of these animals. “My career had barely begun, yet my scientific reputation was under assault,” Beard wrote in The Hunt for the Dawn Monkey, the 2004 book documenting his search for early anthropoids. “There was a lot of disagreement about it,” says Richard Kay, a Duke paleontologist who studies early primates. “Some of us more or less stayed on the sidelines and waited for the evidence to accumulate. And it did, and it supported his argument.” Beard has since found collaborators from around the world to pursue the theory of an Asian origin, including Jean-Jacques Jaeger, a paleontologist at France’s University of Poitiers. Jaeger was looking for early anthropoids in Asia when Beard discovered Eosimias. “Everybody was against him,” Jaeger recalls. “We were in the same boat having to defend our theory, so I said, ‘Why don’t you join us in Myanmar?’” Beard, Jaeger, and a team of scientists have since unearthed a slew of early primate fossils from Myanmar (formerly known as Burma), and now have set their sights on Libya. Their work was interrupted by the Libyan uprising of early 2011, and future expeditions remain on hold pending the country’s political turmoil. An A-team of paleontologyNone of the work Beard has done would be possible without these types of meaningful collaborations. “One person doesn’t just march off into the desert in Libya and find all these fossils—it would be virtually impossible to do that,” he says. About a dozen scientists worked the Dur At-Talah site—an “A-team of paleontology,” Beard says. By day, they picked through piles of earth and mud looking for millimeter-sized fossils. At night, they talked about what they’d found, and, most importantly, what it might mean.

Chris Beard (at right in photo) and French colleague Xavier Valentin examine blocks of rock for fossils at Dur At-Talah. Valentin uses recycled water to dissolve the blocks into sludge so it can then be sifted.

Ultimately, it’s all about one thing: evolution. Whether studying the ankle of Eosimias or the teeth and jaws of Afrotarsius, a small anthropoid from North Africa, Beard is trying to complete a picture of how these early primates evolved, and how the evolutionary process made us who we are. “Much of the research that has always been done at Carnegie Museum of Natural History deals with evolution,” says Beard. “We’re not just studying the endpoints of the animals we study, whether they’re early anthropoids, living mammals, or bugs. We’re interested in the evolutionary history of the animals we study.” Taylor says Beard’s work is a key contributor to the museum’s mission to produce new knowledge about natural history. “For a research-based museum, that’s our primary output, after the public education that happens at the museum,” Taylor says. “Chris is an originator of completely new ideas and pursues new angles to test his theories. That’s why you see him on expeditions in places like Libya, Myanmar, and China.” And now, new technology is allowing Beard to go inside his fossils. At the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, he’s taken some of his Myanmar fossils to a special high-powered x-ray that sees through rock. The synchrotron, a large ring the size of a football stadium, accelerates x-rays at the speed of light, allowing scientists to shoot x-rays a trillion times brighter than those used in hospitals in order to examine objects on the atomic level. Beard imaged the jaw of Ganlea megacanina, a species he discovered in Myanmar in 2005. “When I found that fossil, it was lying on a little toadstool of earth, and it had been exposed to too many monsoon rains,” says Beard. He used the synchrotron to study detailed aspects of the roots of the animal’s teeth, without breaking its jaw open. “Before, we probably never would have even attempted to see this anatomy—you’d have had to destroy the fossil. Now this new technology opens up all kinds of new studies we can conduct.” There are many more questions Beard and his colleagues want to answer. What happened when the anthropoids came to Africa? How did they spread around the world? And, how did they—these early monkeys—become us? Like many secrets embedded in fossils, it’s a story that is still being written. When Beard and his colleagues are able to return to Libya, no doubt they’ll be writing a few more chapters.

|

||||||

Spacewalker · Pittsburgh Bred · The Ragnar Kjartansson Experience · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: John Wetenhall · About Town: Show-stopping Science · Science & Nature: Remembering Brad · Artistic License: Mixed Signals · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |