|

||||||||||

|

The work of 60 artists and artist groups will be on view across five venues as part of the seven-month-long Biennial.(From left to right)

|

Pittsburgh Bred

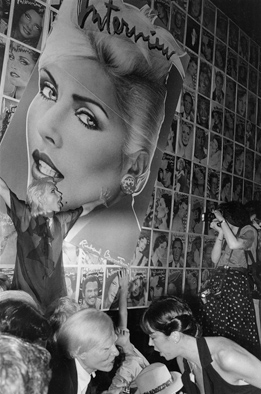

The upcoming Pittsburgh Biennial offers a new precedent of collaboration among the city's major art institutions, all in the name of showcasing Pittsburgh-nurtured talent. Squirrel Hill native Jill Freedman didn’t know she was a photographer until at age 26 she borrowed her friend’s Leica camera and hit the streets of New York City. It was 1966, an era when a walk with her dog would bring her eye-to-eye with strutting prostitutes, kids posing in front of a porn theater, and slack-eyed sidewalk dwellers. “New York back then was raving loonies and everything else,” Freedman says. “You would stand on 42nd Street and hear every language. It was great fun and pre-gentrified. I shot everything I saw. It was about how society doesn’t work for a lot of people.” After she sprang for her own camera, people would ask the self-taught photographer which lens she favored. “Whatever lens is on my camera,” she’d reply. Freedman went on to publish seven books of penetrating photographs and exhibit her work to critical acclaim, until in 1988, after contracting breast cancer, she put down her camera and headed south to Miami to recover. When she returned to New York in 2002, she was disgusted by the newly commercialized Times Square. Worse, she was now nearly as down-and-out as the people she had once captured on film. She had trouble finding a place to live, preserving her negatives in a locker.

A signature show for Pittsburgh Filmmakers/Pittsburgh Center for the Arts (PF/PCA) since 1994, the Pittsburgh Biennial expands its scope this year by adding new partners—The Andy Warhol Museum, Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU). All five venues are pooling their exhibition space and creativity to showcase a wide variety of talented artists who work or once spent significant time in Pittsburgh—some long-known to the show’s curators and the Pittsburgh public, others freshly discovered.

The idea of an expanded platform started a year ago when Charlie Humphrey, executive director of PF/PCA, asked Tom Sokolowski, former director of The Warhol, to partner on the Biennial. “Absolutely,” Sokolowski said. Encouraged, Humphrey extended invi-tations to the Miller Gallery at CMU and Carnegie Museum of Art. Both jumped at the chance to create a unified city-wide “It’s always great fun to partner with an organization that is like-minded,” says Humphrey. “People who go to The Warhol may not have been to the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts or the Miller Gallery. We are broadening the entire ‘Carnegie’ community.” Lynn Zelevansky, The Henry J. Heinz II Director of Carnegie Museum of Art, says she and her staff relish the opportunity. “We want to support artists from Pittsburgh, and we feel the best way to do that is through the kind of curated exhibitions we do for everyone else,” says Zelevansky. “We think local artists deserve that level of consideration.” Poetic spacesThe 2011 Pittsburgh Biennial will be a nearly seven-month-long affair, with four exhibitions opening in two waves. Contributions by Carnegie Museum of Art and PF/PCA will open in June, with very different offerings at The Warhol and the Miller Gallery debuting in September.Each venue’s curator has organized its upcoming exhibition around a distinct theme.

One gallery will showcase 30 paintings and sculptures by Fabrizio Gerbino, a resident of Stowe, Pa., who grew up in the art-drenched city of Florence, Italy. As a boy, Gerbino learned painting from his father, Eugenio, a production artist and factory worker, who gave his son lessons As a young artist, Gerbino drew inspiration from classical masterpieces, as well as from the industrial suburbs of Florence, where his family lived. In 2003, his marriage to Cynthia Lutz of Stowe brought him to a new industrial landscape—western Pennsylvania. One of his first outings in Pittsburgh was a bus trip to Carnegie Museum of Art. Maybe one day I will show here, he thought as he marveled at the paintings. While preparing for the Biennial, Gerbino visited a recycling plant on Neville Island. Inspiration came when he caught a glimpse of a stocky laborer at work in a control room that looked as futuristic as a Star Wars set. That scene inspired five abstract paintings with fragmentary images that will debut at the exhibition. Other paintings are striking monochromatic compositions of a gas holding tank, deserted platforms at a defunct Italian zoo, and his deceased father. Other artists will put their own unique spin on the notion of labor.

“I am really interested in the idea of labor toward a goal that is ephemeral or ridiculous and to let the audience in on it,” Clayton says. “Somewhere in the gap is a real poetic space.” When Byers approached Clayton about creating a piece for Carnegie Museum of Art, her first inclination was to decline due to timing; she’s pregnant with her first child. But then inspiration struck, and she decided to create an installation centered on a baby monitor. “I am going to be home with my newborn baby,” Clayton says. “The microphone in the house will transmit the sound to the museum. You will hear the sound of parallel life that is on the other side of the city.” Clayton, whose native England offers new mothers paid maternity leave, is grappling with the fact that her adopted country doesn’t provide such assistance to independent artists, a situation a small stipend from Carnegie Museum of Art will help. Embroidery and Trojan squirrelsThe Pittsburgh Filmmakers/Pittsburgh Center for the Arts Biennial exhibition will run from June 10 to October 23 and focus on a variety of installations by 16 artists, says curator Adam Welch.It will feature new work by William Earl Kofmehl III, an artist with flowing red hair who incorporates performance, sculpture, and video cameos from his family members into his incredibly personal artwork. With a flair for the grand gesture, Kofmehl makes people laugh and think at the same time.

The curatorial team behind the 2011 Pittsburgh Biennial (left to right): Dan Byers of Carnegie Museum of Art, Astria Suparak of the Miller Gallery at Carnegie Mellon University, Eric Shiner of The Andy Warhol Museum, and Adam Welch of Pittsburgh Filmmakers/Pittsburgh Center for the Arts.“He is a really interesting character,” Welch says, “and a smart individual who performs a lot of scenarios where he interacts with his family.” For his controversial 2002 senior project at CMU, Kofmehl donned a lobster outfit, took a vow of silence, and moved into a wooden shelter he constructed on campus, earning him national fame as “Lobster Boy.” At tourist attractions ranging from the Lincoln Memorial to the temples of Greece, he dove from a small stand and crashed spread-eagle to the ground. And at a 2010 gallery show in New York, Kofmehl appeared with famed subway vigilante Bernie Goetz, several live squirrels, and a giant wooden “Trojan squirrel.” “The squirrel embodies Bernie,” says Kofmehl, adding that the icon of rage is an expert squirrel husbandrist. For the Biennial, Kofmehl is developing an aluminum cast of himself midair during one of his public dives. The exhibition will also include embroidered canvases designed by Kofmehl and sewn by 12 women in Monteverde, Costa Rica. (His sister, Amy Kofmehl-Sobkowiak, is cofounder of Women of the Cloud Forest, a fair trade organization.) An installation by Natalie Settles will feature a large wall drawing that grafts plant specimens and Victorian botanical motifs together in a fusion of the imperfect and ideal, organismic and genomic, and the human-made and natural. Luke Loeffler, a graduate student at CMU’s School of Art, will present an interactive work that “prompts us to consider how we acquire knowledge of complex systems from limited experiential data.” Art laborersWhile some artists toil alone in their studios, many synthesize creative energy with others. The Miller Gallery’s Biennial contribution, debuting September 16, will feature new installations and recent work by collaborating artists.

The groups selected for the Biennial, she says, “will explore the ideas of cultural production, value, borders, sovereignty, and self-reliance.” One such group is Temporary Services, with artists based in Chicago and Copenhagen, Denmark. They will present a “Self-Reliance Library” with publications covering topics such as visionary architecture, wildly imaginative mobility, nomadic living, self-publishing, technologies used in prisons, survivalism, and skill-sharing. Lize Mogel, a CMU graduate living in New York, in collaboration with Ryan Griffis and Sarah Ross of Chicago, will produce an installation about the impact that mega-events “They’ll explore the relationship of spectacle to displacement—who gets pushed out, which neighborhoods are razed,” says Suparak. The fate of a local abandoned building will be the focus of Transformazium, a group of young artists who, three years ago, moved from New York City to North Braddock, a struggling suburb about 10 miles east of Pittsburgh. Caledonia Curry bought an old church with the possibility of creating a community art center. Along with artists Ruthie Stringer, Dana Bishop-Root, and Leslie Stem she reached out to neighbors through urban gardening and a screen-printing shop, and set about renovating the church by first tearing down a section that had been ravaged by fire. Instead of paying $15,000 for professional demolition, they opted to buy tools, roll up their sleeves, and deconstruct the damaged section by hand. This saved $5,000 and allowed them to reuse the brick and materials. “Deconstruction does this magical thing,” Stringer says. “It totally flips the equation. Instead of seeing a neighborhood as full of blight, we see it as full of resources.” For the Biennial, Transformazium will use bricks collected from the deconstruction to build an installation that includes a “psychic embodied brick booth.” Woman PowerAcross town, The Warhol’s portion of the exhibition, which runs September 17 to January 8, will feature another artist with a Braddock connection. Visual artist LaToya Ruby Frazier, who was born and raised in Braddock and is known for her unflinching family photographs, will exhibit new work in response to Levi’s® 2010 “Go Forth” campaign featuring her hometown.

Dana Bishop-Root (left) and Ruthie Stringer of the artist group Transformazium inside what was once the United Brethren Christ Church in North Braddock.“LaToya is burning up the art world right now,” says Eric Shiner, acting director of The Warhol. “There is a secret agony in her strikingly beautiful and hard photographs.” Frazier is one of 22 female artists featured in The Warhol’s exhibition, titled Gertrude’s/LOT, a nod to author and poet Gertrude Stein. North Side artist Diane Samuels is basing her contribution on the words of Stein, who was born half a mile from Samuels’ studio and made her literary reputation writing in Paris. To create the new piece, Samuels will employ techniques from her previous work, Leaves of Grass, a text-based drawing that incorporates the poetry of Walt Whitman. With a monk’s concentration and an athlete’s endurance, the reed-thin artist hand-transcribed Whitman’s 438-page classic into a striking 92-by-33-inch “field of grass” in which each blade represents a line of poetry. “I am a laborer,” says Samuels, who paused for hourly yoga stretches while she toiled away at the project.

" William Earl Kofmehl III with his “Trojan squirrel” at the 2010 Lombard-Fried Project in New York. The live squirrel belongs to Bernie Goetz, the infamous New York subway vigilante who inspired Kofmehl’s sculpture.By contrasting the distance of a viewer with the intimacy of a reader, Samuels will now transcribe one of Stein’s works, possibly The Making of Americans. She drew inspiration by studying the bluestone sidewalk outside Stein’s childhood home on nearby Beech Avenue. “Whitman looked at the world from the United States out. Stein looked at the United States from the outside in,” Samuels says. “I have been going through texts that deal with coming home, with understanding what it means to live in one place while being a citizen of another.” Shiner sees Stein as a creative luminary who paved the way for later generations of female artists in Pittsburgh. “There have been so many hugely talented Pittsburgh women who play on the national landscape,” Shiner says. “Gertrude Stein was one of the power players. Many of the artists inherited her legacies, not only in the art world but in society in general.” Jill Freedman is one of those national stars. Though she spent her childhood in Squirrel Hill dreaming of moving to New York and seeing the world, she is thrilled to return to her hometown to exhibit at one of the Carnegie Museums. “The Carnegie is so special,” says Freedman. “Carnegie Library saved my life,” noting

|

|||||||||

Spacewalker · Tracking the Origins of Humans · The Ragnar Kjartansson Experience · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: John Wetenhall · About Town: Show-stopping Science · Science & Nature: Remembering Brad · Artistic License: Mixed Signals · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

The nine artists showing at Carnegie Museum of Art from June 17 to September 18 will explore the concept of “work as it relates to more abstract notions of labor, economies, and industries,” says Dan Byers, the museum’s associate curator of contemporary art and its Biennial curator.

The nine artists showing at Carnegie Museum of Art from June 17 to September 18 will explore the concept of “work as it relates to more abstract notions of labor, economies, and industries,” says Dan Byers, the museum’s associate curator of contemporary art and its Biennial curator.