|

|||||

|

For the Birds... and the Environment

As the renowned bird-banding program at Powdermill Nature Reserve celebrates a half century, its long-term data about migrating songbirds is informing today’s most pressing environmental issues of climate change, habitat loss, and population change. Drew Vitz sits in a chair, bird in hand, thinking about evolution. The brown head of a wood thrush pokes out from a gap between his second and third knuckles, serenely surveying the room around it. Its body is snug in Vitz’s closed hand. The wood thrush is one of dozens of songbirds Vitz and a small cadre of helpers retrieved from mist nets that morning at Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Nature Reserve. Vitz is an avian ecologist and bird-banding coordinator at Powdermill, a 2,200-acre research center nestled in a green valley of the Laurel Highlands. One of his chief duties is to run the reserve’s renowned bird-banding station, which turns 50 this year. Mainly from spring through the fall, staff capture scores of birds, identify them, record their age and sex, measure and weigh them, then slip a numbered aluminum ring around their legs. This allows scientists to track the movements of migratory birds—and some 520,000 and counting have been banded at the Rector station over a half century. Powdermill bands have been discovered from Peru to Canada, and the reams of data produced by the banding program are a gold mine for scientists like Vitz, who study birds with the express goal of preventing their ultimate extinction and detecting potential problems in the environments they frequent.

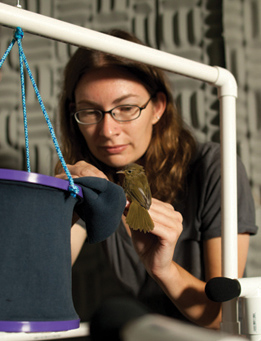

Banding coordinator Drew Vitz, Photo: Josh FranzosPowdermill is the centerpiece of the museum’s new Center for Biodiversity and Ecosystems, headed by entomologist John Wenzel. “As a research unit, Carnegie Museum of Natural History is small, especially in comparison to major universities, but because of our extraordinary collections and resources, we have a huge reach,” Wenzel says. “We certainly have a great platform, and Powdermill is a big part of that, especially when it comes to issues of conservation.” Powdermill has proven, time and again, that there’s plenty to learn from bird banding. Case in point: the wood thrush peeping out from Vitz’s hand. It’s a typical Neotropical migratory bird, he explains. It breeds in the forests of the eastern United States and winters in the Yucatan. Scientists have learned that wood thrush populations are plunging, largely due to human impacts on their habitat. Wood thrushes breed in eastern North American forests that have been fragmented by logging and development for the last couple of centuries. The disruption has left an opening for a particularly sneaky and clever interloper: the brown-headed cowbird. The cowbird doesn’t build its own nests, but instead lays its eggs in the nests of unwitting “host” species, such as the wood thrush. Often, these “guest” nestlings hatch first and push the host young out of the nest. Much of the food that would have gone to the wood thrush’s offspring instead goes to the cowbird’s.

In the meantime, long-term banding data at Powdermill is being analyzed to determine whether there is evidence for a decrease in songbird breeding, which is what Vitz expects if brown-headed cowbirds are in fact having a substantial impact on the ability of adults to produce young. Before Vitz can finish processing the wood thrush in his hand, an assistant, equipped with a pair of banding pliers, quickly affixes an aluminum band around the bird’s leg. Then Vitz checks its sex, examines the molt pattern on its wing to estimate its age, measures its wings, and weighs it. He then opens a tiny window slot next to his desk, holds the wood thrush outside the window, and releases it. The bird flies away, eventually to Mexico for the winter. The right place at the right timePowdermill was established in 1956, a gift of 1,160 acres from General and Mrs. Richard K. Mellon and Mr. and Mrs. Alan M. Scaife to Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Former museum director Graham Netting (at the time an assistant director) was determined to create a biological field station like that of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Among its first uses was bird banding. Meadville native Bob Leberman, a self-taught birder, took the project under his wing. After piloting the program for a few years, Leberman, now in his mid-70s and an active emeritus researcher, was eventually hired to manage it, and was succeeded 35 years later by Bob Mulvihill and Adrienne Leppold, who also began as bird banders at the reserve.

Photo Josh FranzosVitz, who arrived in 2008 from Ohio State University where he studied the impacts of deforestation on the survival rates of songbirds, is only the fourth director of the bird-banding program. That’s partially why Powdermill holds such a special place in the avian world. Not only is it the oldest continually operational bird-banding station in the country; rarer still, only a handful of people have directed the program, ensuring a continuity and consistency critical for scientists in making long-term observations of bird behaviors and physiology. This positions the reserve, and its science staff, as attractive research partners. The reserve’s meticulous data, for example, has allowed a group of researchers—a mix of Powdermill staff and outside scientists—to track how climate change is shifting arrival and departure times of migrating birds. In a recent study that made headlines internationally, Powdermill data showed how warmer temperatures were making songbirds—especially those that travel long distances to migrate—markedly smaller. Josh Van Buskirk, a Powdermill research associate and scientist at the University of Zurich who grew up not far from the reserve, wanted to test the scientific principle that animals shrink in size in warmer climates. So he worked with Powdermill staff to study data from more than 486,000 birds of about 100 different species banded at the reserve from 1961 to 2007. He found that most species gradually declined in body mass and wing size over the past five decades, as temperatures have gradually increased.

Photo: Joe Stavish“Powdermill’s longevity and continuity make it probably the most valuable dataset from a single station in North America, out of the thousand or so we track,” says C.J. Ralph, a research wildlife biologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Station, in Arcata, California. “Less than a half a dozen people have banded the vast majority of birds at Powdermill. That has lent a consistency and accuracy that’s unmatched. In the Americas, there isn’t anything that even comes close to it, for the number of birds caught.” Most monitoring stations are in mountain passes or along ocean and lake shores, creating bottlenecks of birds. Powdermill lies in a typical Appalachian valley, along a popular migratory route between their northern breeding and southern wintering ground.

On May 14, International Migratory Bird Day, bird lovers and nature enthusiasts of all ages celebrated 50 years of bird banding at Powdermill.Photo: John Altdorfer“Because our banding station is a small patch of habitat in a forested landscape, birds are not especially concentrated,” explains Vitz. “So in order to capture meaningful numbers of birds, we need to set up many more nets than most stations. But this creates a key benefit: Our data provides a much better picture of what is going on throughout the Appalachians.” Looking and listeningVitz, who was drawn to avian research as a way to approach conservation on a broad scale, believes bird banding will become more sophisticated as technology improves. On the horizon, he says, is the implantation of miniaturized satellite telemetry devices that birds would carry like a backpack to produce even richer datasets. More detailed information could tell us why, for instance, some bird species are in decline. “We’ll know better where they go, how they’re surviving,” he says. “Maybe the ones going to the Caribbean aren’t surviving very well, but the ones that go to Mexico are doing much better. We’ll get to learn a lot more details about these birds that we just have no idea about at this point. Such information would pinpoint where limited conservation dollars should be spent, representing a huge advancement for conservation.” One way Powdermill scientists are already uncovering new details on the birds they band is by eavesdropping on them. The reserve’s Bioacoustics Lab has set up listening posts throughout the property to listen to flight calls made by passing birds at night, when migration occurs. Flight calls are single-phrase utterances that birds use to direct each other during a long flight. “Powdermill’s longevity and continuity make it probably the most

valuable dataset from a single station in North America, out of the thousand or so we track.” - C.J. Ralph, research wildlife biologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest ServiceOn a ridge atop the reserve are three small towers, each outfitted with simple listening devices. Powdermill has been recording birds for eight years, and has one of the most thorough flight-call libraries in the country. Microphones record all night every night during migration seasons. On a single night, the center can record 20,000 calls of migrating birds, as they soar hundreds of meters above the treetops. By recording signatures, they can detect which species of birds are using the valley as a pass-through. Amy Tegeler, an avian ecologist who runs the reserve’s bioacoustics program, uses computers to analyze the sounds and render them into visual representations called spectrograms. “Here’s what a flight call looks like,” says Tegeler, hoisting up a poster with 28 different species of warbler. Beside each picture of a bird is its spectrogram—some are short and thick squiggles, like a caterpillar, others are more jagged. The calls last under a second, but each is distinctive, and each is a signature. Tegeler also brings banded birds into the recording studio, to study how birds communicate. Powdermill researchers have recorded some 5,000 individual bird calls, including the first recordings of five warbler species. Tegeler says any clues yielded by the flight calls will be invaluable in understanding bird migration. “It’s very important to understand what’s driving them, their timing, their location,” she notes. “All of these aspects are important for us to be able to figure out the best way to conserve bird populations in general.” A bird’s-eye viewPowdermill is also helping researchers try to make the world safer for birds. One of the biggest dangers for migratory birds is a mainstay of the built world: windows. Scientists estimate that between 300 million and a billion birds die each year in the United States alone from collisions with windows. Powdermill is hosting a study to determine whether certain types of glass might be more noticeable to birds, in order to decrease the number of bird deaths. Birds are put into an experimental test tunnel, a trailer-sized wooden structure. At one end of the tunnel are two windows. One is clear, another is embedded with an ultraviolet pattern, which birds see. Netting in front of the glass catches birds before they hit the glass, but not before researchers can tell which pane the birds veered toward. All birds are in danger of colliding with windows, says Christine Sheppard, an avian ecologist with the American Bird Conservancy who is managing the experiment in partnership with Powdermill. Species as rare as the Cerulean warbler—once one of the most abundant breeding warblers in Ohio and the Mississippi River Valleys but now a high conservation concern—fall victim. “If you kill one cerulean warbler, that’s a sizable percent of the population.” Sheppard says. “The bottom line is the amount of glass in the environment is increasing at a really rapid rate.” Wenzel, who is quick to note that this is just the kind of new research that wouldn’t land at Powdermill without the reputation of its bird-banding program, adds that initial study results are already providing simple but exciting and useful information. Creating glass that includes vertical reflecting patterns, which birds can see but that are largely invisible to humans, for instance, is more effective than adding horizontal patterns.

Wenzel arrived at Carnegie Museum of Natural History earlier this year following a career as an entomology professor and director of the Ohio State Museum of Biological Diversity. He views bird-banding research as just the beginning for Powdermill. “It certainly defines our identity, and proudly so,” says Wenzel. “But our hope and plan is to expand our research so that we become well-known for other things.” Forest ecology and landscape management could be among natural areas of study, he notes. Powdermill’s property once included three coal mines. And its forest is only 50 years old in places, and older in others, so it’s perfect in some ways to study the ecology of second-growth forest, which covers most of the east. Researchers from as far away as Vermont and Texas come to Powdermill to conduct field work. Wenzel envisions more of this activity through collaborations. The museum doesn’t have graduate students, who do much of the footwork for research, but universities do, and Wenzel is eager to bring more of these students to the reserve. After all, more than 50,000 woody plants have already been catalogued on the reserve. So birds are just part of the story Powdermill can tell, he says. The ultimate goal of studying the ecology of the reserve, he says, is to better preserve it for future generations. “Really, what we want to do is make sure that the enriching character of the natural environment—whether it’s for recreation, beauty, or inspiration—is something we protect.” Humans can survive in a world without biodiversity. But the grand question that Wenzel, Vitz, and other scientists at Powdermill might ask is simple: Would we want to live in such a world? “In all kinds of people, there’s this human feeling that nature is good,” says Wenzel. “A lot of us who study it do so because we find it gives rich meaning to life. To me, it’s not that different from art or music. I study it because it is inspiring and beautiful.”

|

|||||

In Praise of the Superhero · Picturing Pittsburgh · The STEM solution · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Kristoffer Smith · Science & Nature: Big on Brains · Artistic License: Architectural Wonder · First Person: Summer Dreaming · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |