Fall 2011

Fall 2011|

“Up to his time, architecture was something applied to palaces and churches. The point [Palladio] was making was that it should also apply to barns and bridges—that good design should be pervasive.” - Charles Hind, Royal Institute of British Architects

|

Architectural Wonder

A traveling exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art’s Heinz Architectural Center provides a glimpse into the work of one of America’s greatest architectural influences. By Christine H. O’Toole

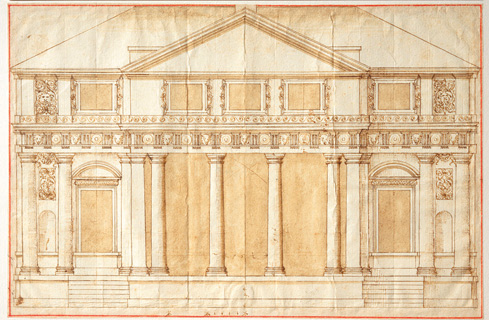

Andrea Palladio, Design for the Villa Repeta at Campiglia: facade, early 1560s, Royal Institute of British Architects, British Architectural Library, XVII/21rArchitects have made monumental marks on the built landscape of the United States over the past 230 years: among them, Michael Graves in the 21st century, Frank Lloyd Wright and Philip Johnson in the 20th, Louis Sullivan in the 19th, and Thomas Jefferson in the 18th. The visionary who deeply influenced all of them, inspiring the vernacular of American architecture, is one who never left Renaissance Europe: Andrea Palladio. Palladio’s meticulous drawings, made more than 400 years ago, are the centerpiece of Palladio and His Legacy: A Transatlantic Journey, on view at Carnegie Museum of Art’s Heinz Architectural Center from September 3 through December 31. “As a body, as an archive, the Palladios are incomparable—the most important group that we have in the collection,” says Charles Hind, associate director and H. J. Heinz curator of drawings at the Royal Institute of British Architects in London, which organized the exhibition with the Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio, Vicenza. Palladio’s theories of proportion, harmony, and simplicity not only inspired 18th-century buildings in Britain, but also formed the foundation of a distinctly democratic style in the United States. Writing last year in Slate, critic Witold Rybczynski dubbed Palladio “the godfather of American civic architecture.” “In some ways, Americans have been more Palladio’s true heirs than the British,” Hind acknowledges. “We invented Anglo-Palladianism, but it was a phase we passed through. In America, it remained a constant presence”—in buildings from the Supreme Court to the New York Stock Exchange to Monticello. Interpreting the historic drawings with scale models, the exhibition comprises three sections that examine Palladio’s classical influences, his own work, and its impact on America. Tracy Myers, curator of architecture at Carnegie Museum of Art, says the models “make it easy to make connections” among such buildings as the ancient Roman Pantheon, Palladio’s famous Villa Rotonda, and the Smithsonian’s National Gallery of Art. “Antiquity yielded architectural ideas that continue to be relevant today, at least in the West,” she notes. Palladio was born in 1508, as the Italian Renaissance embraced the ancient cultures of Greece and Rome. “Both from his base in Vicenza and on trips to Rome, he was looking back to antiquity,” says Myers. His ink drawings of the Colosseum and Pantheon and other ruins show a gifted craftsman, trained as a stoneworker, teaching himself to become an architect. He later synthesized classical elements such as pediments, domes, and columns for designs throughout the Venetian republic. Vicenza has been named a World Heritage site for its wealth of Palladio’s works—not only grand cathedrals, but country villas. “Up to his time, architecture was something applied to palaces and churches,” says Hind. “The point he was making was that it should also apply to barns and bridges—that good design should be pervasive.” That democratic notion resonated deeply with Thomas Jefferson. He called Palladio’s famous treatise, The Four Books of Architecture, his “bible.” (One of Jefferson’s personal copies of the work was rediscovered in 2010, in the collection of Washington University in St. Louis.) Jefferson named Monticello for the hilltop site of Palladio’s Villa Rotonda, a “little mountain.” Models of two Jeffersonian designs in the exhibition—the Virginia State Capitol and the unusual domed President’s House that was his anonymous entry in a 1792 design competition for what we now call the White House—show the beginnings of an American Palladian aesthetic. Quickly adapted for grand Newport mansions and southern plantations alike, the style also became synonymous with this country’s government and commercial buildings. Appropriately, the exhibition made a stop in the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., where so many institutions share Palladian genes. Author Calder Loth, a co-curator of the exhibition, writes in the show’s catalogue that the interpretation of ancient classical forms also provided “an image of dignity and permanence” to hundreds of other institutions, particularly banks. The New York Stock Exchange, built in 1903, follows Palladio’s precept that temple fronts should be “large and splendid.” Loth notes that the building’s vast Corinthian portico “comforts us into thinking that our investments are secure within this temple of finance.” He adds, “Despite the vicissitudes of the stock market, the Stock Exchange’s portico remains a reassuring symbol.” Students of architecture and architectural history throughout the tri-state area are among those seizing this rare opportunity to see the Palladio drawings in Pittsburgh. They are invited to an academic symposium at the Museum of Art on September 24. And an October 20 Culture Club event, open to the public, will decode “what Palladio achieved and why it’s so great.” Myers notes that this partnership between the Royal Institute and the Heinz Architectural Center stems from their shared patron, Drue Heinz. “She was eager for us to collaborate, and we’re very pleased that we can bring the exhibition to Pittsburgh,” says Myers, who vividly recalls the impressions of her first trip to Vicenza’s Villa Rotonda. “The opportunity to be so close to drawings made by the hand of an extraordinary architect is thrilling,” she recalls. “This exhibition connects the distant and recent past with the present.”

|

In Praise of the Superhero · For the Birds … and the Environment · Picturing Pittsburgh · The STEM solution · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Kristoffer Smith · Science & Nature: Big on Brains · First Person: Summer Dreaming · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |