|

||||||||||||||||

|

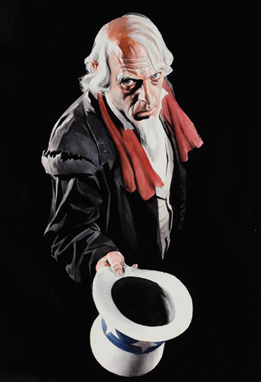

Alex Ross, Absolute Kingdom, Come, Collection of the artist, All characters are ™ & © DC Comics.

|

In Praise of the Superhero

The Warhol shines a spotlight on Alex Ross, one of the great comic book artists of his generation, and the making of a superhero obsession. This past summer, the Steel City transformed into Gotham City for the filming of The Dark Knight Rises, the final chapter of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy. Among the Bat-thrills: thousands of Pittsburghers piled into Heinz Field, cast as fans during a bitter match-up between the Gotham Rogues and their celluloid rivals, the Rapid City Monuments. Inside theaters, in Pittsburgh and around the world, costumed-crusaders and perfectly-chiseled muscle men dominated the big screen: first came Thor and X Men: First Class, tailed by the release of Green Lantern, Captain America: The First Avenger, and Conan the Barbarian. This showcase of superhero stamina is the perfect primer for Heroes & Villains: The Comic Book Art of Alex Ross, opening October 2 at The Andy Warhol Museum, and curated by The Warhol’s director of exhibitions, Jesse Kowalski. Long before Hollywood began regularly pumping super-sized budgets and over-the-top special effects into some of America’s most beloved characters, comic book artist Alex Ross was making a name for himself by making the unreal real. “It very much relates to the world we’re in now, where just about every fantastic concept that’s been applied to the worlds of fantasy characters over the past 75 years is being brought to life in vivid detail in movies, in video games, and with actors in complicated costumes,” says Ross, the preeminent painter of comics. “I was trying to hit that in print form before the reality would support it in other media,” he adds, “because 20 years ago, it seemed the only films we’d ever get about superheroes would be Superman or Batman, and nothing else would ever make their way into cinema.” In a business fueled by distortion, exaggeration, and larger-than-life storylines, Ross, at age 19, introduced his signature brand of photorealism with crushing success.

Yandora was in Marvel Comics’ offices in New York City when he was given a sneak peek of Ross’ rendering of the Human Torch for the four-issue limited series, Marvels. It examined the history of the Marvel universe as seen through the eyes of Phil Sheldon, a press photographer—and it turned out to be Ross’ big break. “I remember immediately being taken back because it was something totally different,” recalls Yandora. “His work is very photographic; he’s able to make the characters look real, not flat on a page. He was an instant standout then and his work continues to carry a huge impact.” A super, lifelong obsessionRoss describes comics as “the stepchild” of art forms. “Our business has always been overlooked,” he explains. “Even though the things created from our hands aren’t read by that many people in the whole, they do have an enormous effect. Whether it’s merchandise, toys, cartoons, movies, you name it—it has a real and lasting impact.” Ross, now 41, should know. Like a lot of kids, it was television shows like Super Friends and the Electric Company—which featured a live-action Spider-Man—and later the film Flash Gordon that turned him on to the magical world of superheroes. Not long after he could grip a crayon, he started drawing three of his favorites—Superman, Captain Marvel, and Plastic Man—and over the next three decades he would revisit those same characters time and again.

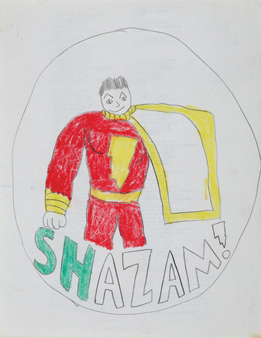

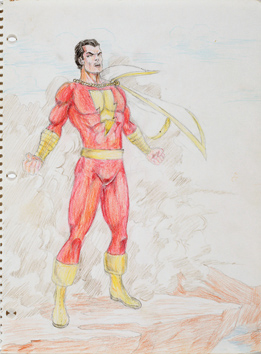

When Ross was 8, the family moved from Portland, Oregon, to Lubbock, Texas, where his minister-father would lead a new church and his parents would continue to instill in him a moral code of right and wrong that fit squarely with his superhero mythologies. As his peers started to drift away from the wonderful world of fantasy, Ross turned to superheroes for companionship. By his own admission, Ross didn’t have a lot of friends as a teen, and spent most of his time alone, drawing. “He copied the style of comic artists like George Perez, who was a big influence,” says curator Jesse Kowalski. “At 13, he was scripting and drawing original comic books.” Kowalski is particularly thrilled to introduce museum-goers to the evolution of some of the artist’s favorite characters. “With Captain Marvel, for example, we have the crayon version he created at age 4, a colored pencil version he did at 15, and a spectacular painting he created not all that long ago, when he was 31,” says Kowalski, noting this is Ross’ first museum exhibition. “They’re just really fun to see next to each other.”

Another must see: a set of seven construction-paper figures of the Justice League, a “good guys” band of superheroes from DC Comics (exhibition sponsor), crafted by Ross at the age of 11. Ross admits he was a little reticent to showcase these earlier works. “I’ve been told that it lends a sense of inspiration for people to see the progression,” he says. “I of course want the impact of my work to crush people. So if they see something I did as a teenager, I want them to think ‘I could never do that.’ I want to crush spirits!” he says, laughing. “The thing about the construction-paper dolls is I made them with an eye for trying to make them seem comical and child-like,” he adds. ”My actual draftsmanship at the time was better than what those represent, so there’s part of me feeling like, ‘Geez, people will judge me because they’re not as good as they could have been.’ But that’s ridiculous, because no one is keeping track!” More than just pretty picturesRoss began his professional journey as a storyboard artist at an ad agency, where he worked for three years before earning his first commercial comic assignment from Now Comics in 1989. The result, Terminator: The Burning Earth, based on the hit Arnold Schwarzenegger movie, caught the eye of editors at Marvel Comics.

Ross went on to win the Comic Buyer’s Guide Award for Favorite Painter so many times the award was retired. Cooler yet: His success gave him the freedom to construct an entire series around his Dad interacting in a world filled by his most prized superheroes. Cue Ross’ sophomore project Kingdom Come, a futuristic story for DC Comics about a minister who intercedes in a civil war between traditional good guys—Superman, Wonder Woman, and Green Lantern among them—and a growing gang of irresponsible new vigilantes. Conceived in part by Ross when he was just a teenager and written by Ross and Mark Waid for publication in 1996, the instant hit was a visual feast that featured a 40-something Superman and a main character based on Ross’ father, Clark.

It was also Ross’ grown-up way of embracing characters that have long been beacons of light and hope—attributes that first attracted him to his livelihood—for a new generation being bombarded by a darker and more violent modern superhero set like Wolverine, the Watchmen, and Lady Death. “[Kingdom Come] was a project that would remain something that fans would talk to me about for the decades that followed, saying how much it influenced them,” says Ross. “It had a life beyond an initial release period. Most things only hit one time and don’t change anyone’s life.” Ross doesn’t downplay the training behind all the glitz, glamour, and bulging muscles. It’s hard work making superheroes stand out. Art school had a huge impact on his technique, he says. Ross studied at Chicago’s American Academy of Art, his mother’s alma mater, where he mastered drawing the human figure. “Prior to that, I thought if you were looking at any form of reference, it would somehow be cheating,” recalls Ross. “But when I had the experience of working from a live model every day in art school, it had a fundamental change on my ability. I discovered that you learn by looking, not just trying to remember. That was a big evolution step for me.” Since then, he’s used his friends, family (including his wife, who he met in Metropolis, Illinois, at a Superman convention), even himself—often dressed in full superhero costume—as live models. He photographs them in his own small photo studio, making sure to capture small but crucial details like hand placement and natural facial expressions. He then uses the photographs as reference to put pencil to paper. Only after an artwork is fully executed in black and white does Ross apply his signature gauche watercolor. It’s a laborious process, part of the reason Ross now mostly concentrates on cover work. He knows that not everyone agrees with that process, or enjoys the result.

Still, even detractors are quick to say Ross sets himself apart when it comes to his technical chops. “What I tend to like about Ross’ work, when I like it, is much less the sense of, ‘Wow, it’s like my retinas are at the right place at the right time,’ than his design sense and color sense, which are strange and wonderful and out of this world,” says comic art critic Douglas Wolk. “He has a way of using color effect that you don’t really see from a lot of other comics.“He has unmatched skill when it comes to what he does,” adds Wolk. “His work is no doubt impressive. It’s visually stunning and incredibly time-consuming. No one can match him on his narrowly-defined turf.” A superhero in the makingRoss’ well-tuned process will be on display in its full glory in Heroes & Villains, which draws from Ross’ lifetime of work, including Marvels, Kingdom Come, Uncle Sam (which Ross calls an effort toward progression and relevance), Justice, Astro City, and Crisis on Infinite Earths (by far the project Ross has spent the most time on). A few of his sculptures and just a tiny sliver of his giant stash of superhero collectibles, some of which he designed himself, will also be on view. (Superman figures, in every form—including a life-size wax replica—fill his suburban Chicago home.) He created a new painting—Andy Warhol flying through the clouds—especially for the show, which graces the cover of the exhibition catalogue-turned-comic-book and will be sold as a poster exclusively in The Warhol Store. “Some of the work is coming directly from the walls of Alex’s home,” notes Kowalski, who was introduced to the artist’s work just two years ago, when he returned to comics after a decade-long hiatus. “I was into comic books as a kid and even a little in college,” recounts Kowalski. “Then I starting working at The Warhol, got married—in essence, grew up—and dropped out of the world of comic books.” In 2009, during the run of The Vader Project at The Warhol, Kowalski took a few of the displays to a local comic convention in hopes of drawing fans to the museum. Comic books were selling 10 for a $1, so he bought a bunch. A lot of them had Ross covers. “Around the same time, my wife got sick,” recalls Kowalski. “She’s better now, but while sitting in waiting rooms, I read a lot of the Justice books. I was really blown away by Alex’s paintings. They were unlike anything else I saw in those stacks or remembered from my childhood.” Also knowing that Warhol was a big comic book collector (many of which will be on view), Kowalski’s interest was piqued. Soon he discovered that Ross drew inspiration from a diverse sampling of popular culture, making him a perfect fit for The Warhol.

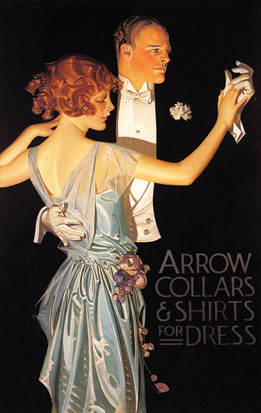

He’s been referred to as the Norman Rockwell of comic book painting so many times, he no longer shies away from the enormous compliment. So it’s no surprise that, on view in Heroes & Villains, are numerous examples of how Rockwell’s signature group portraits form the basis for Ross covers by influencing lighting and textural effects. The exhibition inherently pays homage to the great comic book artists who came before him: Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, John Romita, Neal Adams, and George Perez, among others. As a stylist, however, Ross was also heavily influenced by preeminent American illustrator J.C. Leyendecker and lesser-known Andrew Loomis, whose work graced the pages of national magazines in the 1940s and who penned art instruction books, and whose work is also on display in the exhibition. “What a show like this does is celebrate the medium that gave birth to all of these icons of colorful costumed characters and show that it’s still a vital, living thing,” says Ross. “It reminds consumers that we’re still trying to improve upon our medium, to chart new adventures to build a better comic book and to reach out to an audience that may never have tried comics. Or to people like Jesse [Kowalski], who left comics when they’re young and now have an opportunity to have a rewarding experience as an adult.”

|

|||||||||||||||

For the Birds … and the Environment · Picturing Pittsburgh · The STEM solution · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Kristoffer Smith · Science & Nature: Big on Brains · Artistic License: Architectural Wonder · First Person: Summer Dreaming · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |