|

||

| Casting aside the photographer’s long-held ritual of capturing the decisive moment, Michals introduced image sequences in a cinematic frame-by-frame format in order to tell a story. |

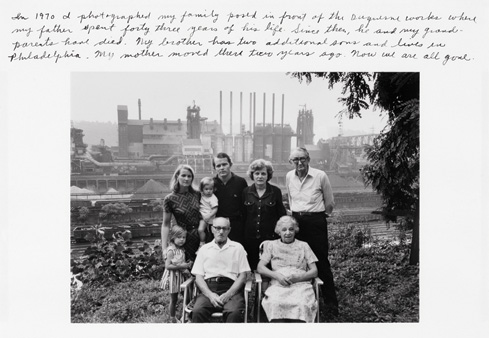

A true original, McKeesport native Duane Michals literally rewrote the once long-held rules of photography by taking charge of the viewer’s experience, and infusing his work with thought, emotion, and humor. Internationally renowned artist Duane Michals is a consummate storyteller, and Pittsburgh is the root of his storyline. That’s why more than half a century after leaving for Denver, and eventually New York City, his longtime home, he returns to the Steel City every chance he gets—for commercial assignments, for high school reunions, for visits to the museum that introduced him to art and is now home to his archive. Among his favorite haunts: The Café at The Frick in Point Breeze, City Books on the South Side, and of course his old stomping grounds in his beloved, albeit now worn, hometown of McKeesport. The oldest son of Slovak immigrant parents, Michals, now 78, grew up in a three-story brick home on unpaved High Street, where his active imagination, which dreamed up adventures in the Big Apple, blossomed. Fellow art star Andy Warhol thumbed his nose at his Pittsburgh roots and never looked back, but Michals—who in the 1960s reinvented the role of photographer from spectator to agent of thought and emotion—has always embraced his modest blue-collar upbringing, relishing its impact on his work ethic. “I’m a fanatic about Pittsburgh, especially McKeesport,” Michals says from the cozy basement office of his 19th-century brownstone on the east side of Manhattan. “I guess it was such an important part of my life and I have good memories. My grandmother told me that if I worked hard, anything was possible. That if I wanted something, to go get it; that nobody was going to give it to me. So that’s what I did.”

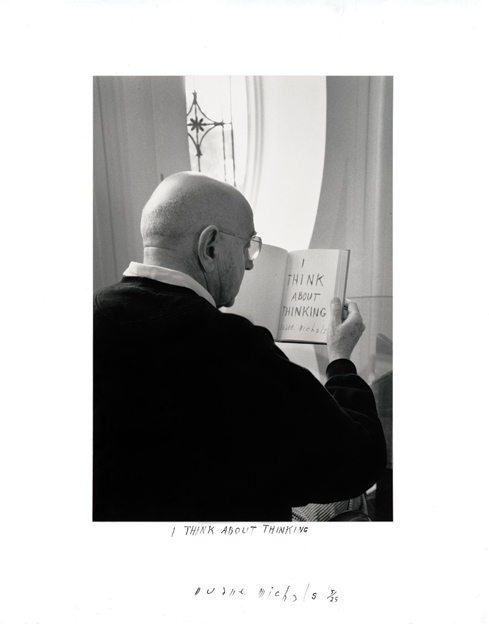

Duane Michals, I Think About Thinking, 2000, The Henry L. Hillman FundIt was in the bookstore of the former downtown Kaufmann’s that Michals discovered one of his greatest inspirations: Walt Whitman. At age 17, he forked over five dollars earned by delivering the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette to purchase Whitman’s well-known collection of poetry, The Leaves of Grass. Drawn to Whitman’s candor, particularly about his close relationships with men, Michals even carried the book into battle during the Korean War, and still owns the same edition today. Like Whitman, Michals is entirely self-taught. Having never formally studied photography, he instead finds inspiration from poets and Surrealist painters such as René Magritte, Balthus, and Giorgio de Chirico. He has always gone against the grain, focusing his camera inward rather than outward. In the process, he has revolutionized the still photograph. Casting aside the photographer’s long-held ritual of capturing the decisive moment, Michals introduced image sequences in a cinematic frame-by-frame format in order to tell a story. He didn’t wait for things to happen; he staged events for the camera. He was also the first to write on photographs.

Duane Michals, I Remember Pittsburgh, 1982, Greenwald Photograph

|

|

Putting the Magic in the Miniature Railroad · The Things They Carried · In Search of the Arabian Horse · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Marilyn Russell · Science & Nature: A Walk with the Dinosaurs · Artistic License: Finding Joy in the Moment · Field Trip: Oh, the Places They Go · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |