A new thrill for an old favorite

As a way to keep fresh what’s believed to be the oldest model train display in the country, if not the world, the Science Center adds a new attraction annually. This year marks the return of Leap-the-Dips, a replica of the world’s oldest standing wooden roller coaster. The full-sized coaster still runs in Lakemont Park in Altoona.

The Science Center’s scaled-down version of Leap-the-Dips, built in 1998, was taken out of commission three years ago because its plastic frame had disintegrated. Its plastic riders were getting too much of a thrill inside cars that often flew off the track or got stuck halfway up the hill. So Rogers opted to rebuild this crowd favorite using brass instead of plastic, and motorize the car so it would no longer rely on gravity. “The whole freefall got us in trouble,” she says with a wink. “Scaling down gravity is hard.”

Rogers tinkers with the display's mechanics

Rogers tinkers with the display's mechanics

She enlisted the help of volunteer Bob Kalan, a retired banker from Mars, Pa., who re-engineered and soldered all the new brass supports. He searched the Internet to track down a tiny motor.

One of Rogers' masterpieces, Fallingwater

One of Rogers' masterpieces, Fallingwater

“Bob has been a gift for the Miniature Railroad,” says Rogers. “He is a jack of all trades, just as handy as can be, and good at electronics.”

She adds that most of her energies on the revamped coaster went into painting the brass so that it looks like weathered wood. It’s all in a day’s work for Rogers, whose job is one part artist, one part craftsman. She always manages to add her artistic flourishes and historic details while meticulously keeping the scale at a quarter-inch to one foot.

In the 1920's, visitors flock to Charlie Bowdish's Brookville home; and in 1954, his one-time hobby evoled into The Buhl's Christmastown Railroad.

In the 1920's, visitors flock to Charlie Bowdish's Brookville home; and in 1954, his one-time hobby evoled into The Buhl's Christmastown Railroad.

“Patty is somebody you could never replace,” says Ron Baillie, the Henry Buhl, Jr., Co-director of the Science Center. “You can find a miniaturist. You can find an exhibit developer. You can find an artist. But when you roll it all together and overlay it with her passion, it’s a combination you just couldn’t replicate.”

“Patty is somebody you could never replace,” says Ron Baillie, the Henry Buhl, Jr., Co-director of the Science Center. “You can find a miniaturist. You can find an exhibit developer. You can find an artist. But when you roll it all together and overlay it with her passion, it’s a combination you just couldn’t replicate.”

Baillie believes that Rogers’ skills are a part of the reason the Miniature Railroad & Village attracts a whopping 350,000 to 400,000 visitors a year and is routinely named as the number one reason to visitthe Science Center.

“It’s so much more than a job for Patty,” says Baillie. “It’s a calling. And it’s contagious.”

The Miniature Railroad is memorable for another reason: It tells Pittsburgh’s story. Included is a piece of just about every city neighborhood plus landmarks from blue-collar towns across the western part of the state. Visitors are quick to rattle off a favorite replica. The Liverpool Street row houses in Manchester. The Lark Inn in Leetsdale. St. John’s Church in Economy. The McKeesport Watch Tower. The Ebenezer Baptist Church in the Hill District. The No. 9 Firehouse in Lawrenceville. The Donora Post Office. Klavon’s Pharmacy in the Strip District. The limestone quarry. H.J. Heinz Homestead on a barge, in transit from Sharpsburg to the North Side, where it moved in 1904.

Building a tradition

As an artistic child growing up outside of Canonsburg, Rogers never dreamed that a job like hers existed. But like so many generations of Pittsburghers, she and her family visited the Miniature Railroad’s previous home at Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, and she was enchanted by it.

As an artistic child growing up outside of Canonsburg, Rogers never dreamed that a job like hers existed. But like so many generations of Pittsburghers, she and her family visited the Miniature Railroad’s previous home at Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, and she was enchanted by it.

The rural landscape of farmhouses and a railroad that crossed over Rogers’ own front driveway inspired her art from a young age. And her junior high and high school teachers occasionally commissioned her to do paintings. While she never wavered in her determination to become an artist, it was hard to make a living.

In 1991, Rogers got her big break. While volunteering at the newly opened Carnegie Science Center, she showed a museum director her portfolio and was commissioned to paint a mural and a few other small projects. A short time later she was offered a job building models for the Miniature Railroad, and she’s never looked back.

One of Rogers’ first tasks was to transfer the Miniature Railroad from the Buhl to its new home at the Science Center, and to construct new buildings for a display that would grow 60 percent larger. Learning by doing, she perfected the techniques that had been pioneered by the man who started the tradition in his home in Brookville, Pa.

"Engineer Don" Leech at work in the Miniature Railroad's workshop.

In 1920, Charlie Bowdish, a disabled World War I veteran with a showman’s flair, first unveiled his miniature railroad as a Christmas Eve tribute to his brother and new sister-in-law at their wedding. Wedding guests were invited to look at the meticulously built village, a replica of homes in Bowdish’s modest-sized town. One guest asked if he could return with a “few friends” to see the exhibit. Six hundred people showed up.

Over the next 25 years, Bowdish’s miniature village kept growing, taking over the second floor of his home and becoming more and more sophisticated. Lionel trains ran through the railroad then as they do now (today’s version stars five trains and a trolley). The crowds grew, too, coming from all parts of the United States to get a glimpse of his handiwork. Officially, the railroad was only open a few hours a day during the Christmas season, but visitors would show up at Bowdish’s front door at all hours, all year long. He always let them in, and never charged a fee.

But his house on White Street flooded one too many times, and his insurance company stopped insuring him. So in 1954, Bowdish found the perfect home for his elaborate hobby: The Buhl, which was looking to expand its own modest miniature railroad. During the transfer, Bowdish stayed in Pittsburgh for the construction of what was renamed Christmastown Railroad. He received $12 a day plus living expenses, and he sold The Buhl more than 30 houses, barns, and other buildings for 50 cents to $1 apiece and 300 trees for 15 cents each.

The display is always a hit with young visitors.

The display is always a hit with young visitors.

Rogers never met Bowdish, who died in 1988. But she learned the trade under Carl Wapiennik, the Buhl director who supervised the Christmastown Railroad and worked with Bowdish. Wapiennik passed on to Rogers Bowdish’s landscaping techniques, including the tip of using wild hydrangea to make trees. Today, the display is filled with more than 250,000 trees, all still made using the same flower.

“Charlie was a tremendous craftsman,” Rogers says, pointing to his buildings that still stand, as well as a replica added several years ago of his house, with people lined outside the door. “He was prolific. He developed many of the techniques we use today, including carving beeswax to make stonework.”

By way of the Science Center, she inherited not just his buildings, but his philosophy.

“He used to say it’s all about texture, texture, texture, creating shadows and creating depth,” says Rogers. “My own apprenticeship was one person removed, but his philosophy and style were passed onto me. A lot of what he said sticks with me.”

It’s all in the details

Bowdish’s words stuck with Rogers last year as she undertook the mammoth challenge of crafting a replica of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, an all-consuming project and her biggest task to date. “I lived and breathed Fallingwater for five months,” says Rogers. “It was daunting to try to recreate a genius’ masterpiece, knowing that every last detail would be scrutinized by scholars who had studied it.”

“It’s so much more than a job for Patty. It’s a calling. And it’s contagious.”

-Ron Baillie, Co-director of carnegie Science Center

Like Wright, she built it from the ground up and inside out. She quickly realized that it posed a special kind of challenge: the design of each floor is different than the next, so constructing each new level was like creating an entirely new model. Fortunately, Fallingwater provided blueprints and elevation drawings. Rogers taped them to her office window. As she’d complete a floor, she’d tape its blueprint to the next to figure out how the two connect.

In every project, Rogers identifies those essential elements that are crucial to get absolutely right in order to evoke the perfect pitch of emotions and memories. For Forbes Field, it was the crowd. For Fallingwater, it was the exterior stone work. She didn’t want to use commercial model builder or modeling stone because it was too even and artificial-looking. The solution came one day when she was walking around her old farmhouse in Cecil Township. She noticed the big flat sandstone on her sidewalk was peeling. With a putty knife, she flicked off the thin layers of rock and cut them into strips that would form the stone work.

“It allowed me to create the randomness of it and the unique attributes on the real Fallingwater,” says Rogers. “I wanted it to have a very organic feel.”

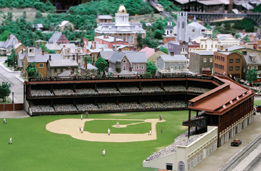

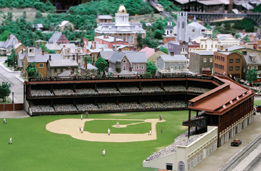

Replicas built by Rogers: East Liberty's 1913 Gulf Station, the country's first drive-up service station, and Forbes Field.

Replicas built by Rogers: East Liberty's 1913 Gulf Station, the country's first drive-up service station, and Forbes Field.

She had planned to decorate the interior with Tiffany lamps, Navajo orange sofas, and artwork, but she simply ran out of time. This year, she improved the home’s waterfall, making it fuller by rigging some fishing wire beneath it to widen its spray.

She had planned to decorate the interior with Tiffany lamps, Navajo orange sofas, and artwork, but she simply ran out of time. This year, she improved the home’s waterfall, making it fuller by rigging some fishing wire beneath it to widen its spray.

Rogers is forever tweaking. Even the color of the river that flows by the Sharon Steel Mill and coke ovens—which, by the way, is filled with real water measuring about three inches deep—is a detail to be fine-tuned. Rogers thought the shade of blue looked too artificial, so last fall she tinted it a deep bronze.

And about those boats floating downstream: They move, says Rogers, with the magic of magnets. Magnets attached to the bottom of each boat correspond to opposing magnets mounted on a geared chain and sprocket system beneath the river. Magnetic attraction carries the boats—one of the favorite features of young visitors—through the water.

While adults and kids alike are drawn to the wonder and history the Miniature Railroad evokes, because it stands just two and a half feet from the ground, a child’s-eye view is the best in the house, says Rogers. It’s the perfect vantage point to spot some of the 102 moving parts—the tree swing, the Ferris wheel, the woman washing clothes, or the motorist trying to crank-start his Model Ford.

One of the best parts of each day, notes Rogers, is watching visitors discover—and discuss—these small moments. It’s in the stories and suggestions of visitors, she explains, where she finds her inspiration.

One of the best parts of each day, notes Rogers, is watching visitors discover—and discuss—these small moments. It’s in the stories and suggestions of visitors, she explains, where she finds her inspiration.

“We have folks who have visited their entire lives and now they’re bringing

their grandchildren,” says Rogers. “The Miniature Railroad is about their stories—where they grew up, where their fathers worked, their own neighborhood Isaly’s.”

Visitors to the Miniature Railroad & Village® at Carnegie Science Center see trains chugging past Forbes Field, circa 1909, a century-old amusement park, Sharon Steel Mill, and Punxsutawney Phil peering at his minuscule shadow at Gobbler’s Knob.

Visitors to the Miniature Railroad & Village® at Carnegie Science Center see trains chugging past Forbes Field, circa 1909, a century-old amusement park, Sharon Steel Mill, and Punxsutawney Phil peering at his minuscule shadow at Gobbler’s Knob.  The latest incarnation, unveiled to the public on November 20, features a rebuilt Leap-the-Dips roller coaster, a freshly laid outfield on Forbes Field, and a more robust waterfall beneath last year’s new addition, Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterful Fallingwater.

The latest incarnation, unveiled to the public on November 20, features a rebuilt Leap-the-Dips roller coaster, a freshly laid outfield on Forbes Field, and a more robust waterfall beneath last year’s new addition, Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterful Fallingwater.  Volunteer Bob Kalan re-engineered all of the new brass supports for the Leap-the-Dips rollercoaster.

Volunteer Bob Kalan re-engineered all of the new brass supports for the Leap-the-Dips rollercoaster.

Rogers tinkers with the display's mechanics

Rogers tinkers with the display's mechanics One of Rogers' masterpieces, Fallingwater

One of Rogers' masterpieces, Fallingwater In the 1920's, visitors flock to Charlie Bowdish's Brookville home; and in 1954, his one-time hobby evoled into The Buhl's Christmastown Railroad.

In the 1920's, visitors flock to Charlie Bowdish's Brookville home; and in 1954, his one-time hobby evoled into The Buhl's Christmastown Railroad. “Patty is somebody you could never replace,” says Ron Baillie, the Henry Buhl, Jr., Co-director of the Science Center. “You can find a miniaturist. You can find an exhibit developer. You can find an artist. But when you roll it all together and overlay it with her passion, it’s a combination you just couldn’t replicate.”

“Patty is somebody you could never replace,” says Ron Baillie, the Henry Buhl, Jr., Co-director of the Science Center. “You can find a miniaturist. You can find an exhibit developer. You can find an artist. But when you roll it all together and overlay it with her passion, it’s a combination you just couldn’t replicate.” As an artistic child growing up outside of Canonsburg, Rogers never dreamed that a job like hers existed. But like so many generations of Pittsburghers, she and her family visited the Miniature Railroad’s previous home at Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, and she was enchanted by it.

As an artistic child growing up outside of Canonsburg, Rogers never dreamed that a job like hers existed. But like so many generations of Pittsburghers, she and her family visited the Miniature Railroad’s previous home at Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science, and she was enchanted by it.

The display is always a hit with young visitors.

The display is always a hit with young visitors. Replicas built by Rogers: East Liberty's 1913 Gulf Station, the country's first drive-up service station, and Forbes Field.

Replicas built by Rogers: East Liberty's 1913 Gulf Station, the country's first drive-up service station, and Forbes Field.  She had planned to decorate the interior with Tiffany lamps, Navajo orange sofas, and artwork, but she simply ran out of time. This year, she improved the home’s waterfall, making it fuller by rigging some fishing wire beneath it to widen its spray.

She had planned to decorate the interior with Tiffany lamps, Navajo orange sofas, and artwork, but she simply ran out of time. This year, she improved the home’s waterfall, making it fuller by rigging some fishing wire beneath it to widen its spray. One of the best parts of each day, notes Rogers, is watching visitors discover—and discuss—these small moments. It’s in the stories and suggestions of visitors, she explains, where she finds her inspiration.

One of the best parts of each day, notes Rogers, is watching visitors discover—and discuss—these small moments. It’s in the stories and suggestions of visitors, she explains, where she finds her inspiration.