Winter 2010

Winter 2010|

“It’s almost as though they were entering an ancient world,

bringing it all to life.” – Jacalyn Cardella. a teacher at st. teresa of avila school |

A Walk with the Dinosaurs

A new generation is falling in love with Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s dinosaurs, and now thanks to Dinosaurs in Their Time, they’re being immersed in their world.

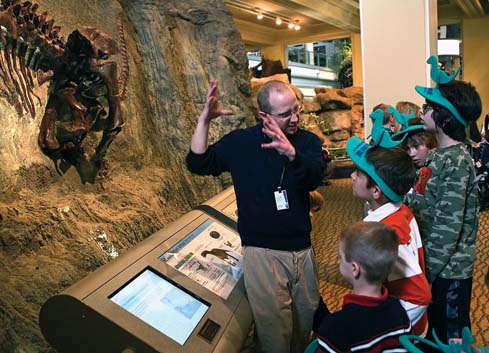

Tours of Dinosaurs are more fun with an animated guide leading the charge. Public, docent-led tours are available on weekends at 1:30 and 3 p.m.By dinosaur standards, this one doesn’t look menacing. Just about the size of a family car, it’s not a towering titan like T. rex. Even so, Herrerasaurus, one of the earliest dinosaurs, isn’t the kind of creature you would have wanted to cross 230 million years ago. Paula Doebler, a docent at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, points out its sharp teeth and claws to a group of fourth graders from St. Teresa of Avila School in Perrysville. Then Doebler does one better. Putting imaginary claws around the neck of Andrew, 9, she asks her pretend grade-school prey: “What is he going to do with those claws?” “Uh, take off my neck!” Andrew says, as his eyes grow saucer-like and his classmates laugh. “Yes, he is going for the jugular,” Doebler says. “He wants to eat you for lunch or dinner or breakfast or anytime he can get you.” Andrew smiles. Learning about how dinosaurs roamed the earth is a lot more fun when you have real dinosaur skeletons towering over you and an animated tour guide leading the charge. For decades, going to see the museum’s dinosaurs has been a rite of passage for regional school children. Now, with Dinosaurs in Their Time, it’s even more of a swashbuckling adventure because it immerses young people in a world where dinosaurs rule but are hardly alone. These 9- and 10-year-olds, for instance, soak in a real skeleton of Diplodocus, and then get a sense of what he fed on thanks to re-creations of the forests and fern prairies that once surrounded the long-necked sauropod. They learn through real fossils and detailed casts that mammals once scurried beneath him. Then, just before they feast their eyes upon the awe-inspiring T. rex, Triceratops, and other Cretaceous Period dinosaurs, which roamed 146–66 million years ago, the students discover that weird-looking reptiles, enormous fishes, and even sea monsters lived among them. As the students wind their way through the dinosaur displays—their necks cocked backward and their eyes peering way up—Doebler intersperses interesting facts. America was once on the Equator. All birds are dinosaurs but not all dinosaurs are birds. Fossils are vestiges of life at least 10,000 years old. But what’s truly impressive, of course, are the dinosaur bones. And the museum has lots of them, boasting the third largest collection of real free-standing dinosaurs in the country. Doebler offers a play-by-play of the likely drama in a scene pitting an Allosaurus against a mother and baby Apatosaurus (the only baby Apatosaurus on display in the world). The charging Allosaurus has its eyes set on the baby, she says, presumably thinking about lunch. “Do you think mommy is going to go for it?” she asks. “No way, Jose. What is the mommy Apatosaurus going to do? Look at her tail. It’s like a whip.” At first glance, the unfolding showdown looks like a mismatch because Allosaurus is dwarfed by the bigger mother beast. But Allosaurus has one important advantage. “We call the Allosaurus the wolf of the Jurassic Era,” Doebler explains. “We think Allosaurus hunted in packs and called in his buddies and said, ‘Let’s get the big one. You get the back leg. You get the front leg. I’m going for the neck.’” The star of the show, however, is not one, but two T. rex specimens, engaged in a fierce battle over dinner, a fallen Edmontosaurus. “Look at those little arms and that great big head,” says Doebler, pointing to the 40-foot-long holotype T. rex, the original specimen by which the species—the world’s most famous dinosaur— is and forever will be defined. The holotype T. rex is extra special, she explains, because when other potential T. rex specimens are discovered the world over, they must first be compared to Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s skeleton to make sure it is in fact a T. rex.

Another fascinating fact, notes Doebler: When a T. rex would lose one of its six-inch-long teeth, another one would grow back in its place. So no dental work for him, she jokes. “Just like a shark!” exclaims a student named Louis. As the tour comes to a close, the docents talk to the students about the theories of how dinosaurs went extinct. Did a giant rock from outer space blast T. rex and his ilk off the face of the Earth? Or was a huge volcanic eruption to blame? Nine-year-old Cade jumps right in. “The food chain was corrupted,” he says. “The plant eaters couldn’t find food and died off, and then the meat eaters couldn’t eat the plant eaters and died off.” Andrea Capone, another docent leading a second group of students from the same class, notes how impressed she is that a fourth-grader has such a sophisticated understanding of the food chain. “Some of them are like mini-paleontologists!” The students’ teacher, Jacalyn Cardella, was thrilled to see them so excited about things they studied in class. “It’s almost as though they were entering an ancient world,” she says, “bringing it all to life.”

|

Putting the Magic in the Miniature Railroad · The Things They Carried · The Expressionist · In Search of the Arabian Horse · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Marilyn Russell · Artistic License: Finding Joy in the Moment · Field Trip: Oh, the Places They Go · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

“We also know T. rex was related to birds,” Doebler continues. “How do we know? How many of you have turkey for Thanksgiving? How many of you know what a wishbone is? Guess who else has a wishbone? T. rex. It’s one of the clues that all birds are dinosaurs.”

“We also know T. rex was related to birds,” Doebler continues. “How do we know? How many of you have turkey for Thanksgiving? How many of you know what a wishbone is? Guess who else has a wishbone? T. rex. It’s one of the clues that all birds are dinosaurs.”