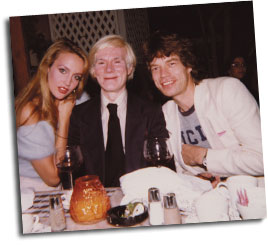

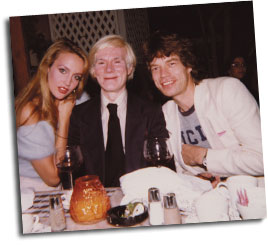

Jerry Hall, Andy Warhol, and Mick Jagger in 1978.

“Up until recently, most curators of Warhol shows were interested in painting, in visual art, and comparing this body of work with those of other artists,” explains Wrbican. “The people responsible for putting together exhibitions weren’t thinking quite as much about other media.”

Beginning in the 1990s, The Andy Warhol Museum situated itself at the forefront of this new way of approaching the artist with exhibitions such as

The Warhol Look, which explored Warhol’s relationship with fashion, and the Wrbican-curated show

Starf*cker: Andy Warhol and the Rolling Stones. Similarly, the artist’s close partnership with The Velvet Underground—the Lou Reed-fronted band he took under his wing —has been illuminated time and again, as the band’s minimalist proto-punk rock has grown as an influence in the past two decades.

Warhol Live is a watershed moment in this view of Warhol’s cultural context. Each section of the exhibition is given over to a specific area of Warhol’s influences and work. One gallery re-creates one of Warhol’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” happenings—multi-media events that featured Warhol’s films as well as the dancing of regulars at Warhol’s studio, The Factory, while The Velvet Underground performed live. Another section, “Fame,” uses Warhol’s Interview magazines, his MTV television show, and other platforms to look at the intersection of the music world with Warhol’s obsession with celebrity; another, his dedication to New York City nightlife and disco mecca Studio 54.

But Warhol Live goes a step further by stressing another point: that to imagine Warhol as only a rock icon or disco maven is to deny him his complex and contradictory nature.

If Andy had an iPod

On September 9, 1963, Andy Warhol was in the audience when John Cage gathered a dozen of New York City’s most notable experimental musicians to create the first-ever performance of French composer Erik Satie’s turn-of-the-century composition, Vexations. For 18 hours, the pianists took turns repeating the piece’s single, simple phrase 840 times, as per Satie's compositional instructions. The performance became one of the seminal moments of American minimalist composition.

Not long after, Warhol created his first, and one of his most famous, art films.

“

Sleep was created after having at least witnessed

Vexations,” says Greg Pierce,

assistant curator of film and video at The Warhol and curator of the film and video material in

Warhol Live. “He utilized those ideas in

Sleep—everyone thinks that the film is just one shot, for five hours, of someone sleeping. But it’s not: He shot a lot of footage and took things that he liked and repeated them. So there’s one shot of the breathing torso looped for, say, 20 minutes, and then another minute-long shot that repeats for an hour.

“Did that come from seeing Vexations? I don’t know,” says Pierce. “But he certainly could’ve been tweaked by that performance.”

Regardless of whether or not Vexations and its ilk directly impacted Warhol’s artwork, there’s little doubt that the artistic world Warhol in habited was electric with minimalism’s avant-garde concepts.

“This music is certainly an influence on Warhol’s pieces that are multiple repetitions of the same images,” says Mathew Rosenblum, chair of the University of Pittsburgh’s Music Department and himself a lauded contemporary composer. “There was something in the air of that downtown scene that he latched onto; someone like [minimalist composer] La Monte Young he would’ve probably viewed as a celebrity. For him to walk out and go see a performance of La Monte Young’s Trio for Strings, which consists of static notes sustained for quite a long while—if Warhol had seen performances of that, I can’t see how it wouldn’t have proven influential.”

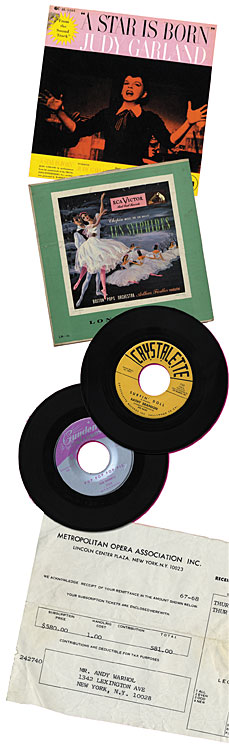

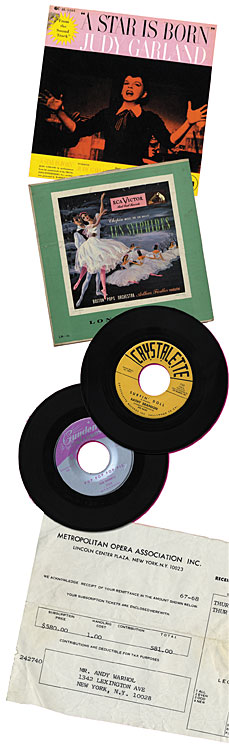

Influential? Doubtlessly. But a look at Warhol’s own listening habits show that the artist kept those influences somewhat at a distance: They had their time and place. As a part of its archives, The Warhol owns the artist’s personal recordings, and as a part of Warhol Live, for the first time a selection comes into the public eye. And just like the unopened Charlie Parker set, what’s not there is as interesting as what is.

No avant-garde compositions or contemporary minimalists; no Erik Satie, no La Monte Young, not even modern jazz. And besides his beloved Rolling Stones and Velvet Underground, there aren’t even many rock records among Warhol’s possessions. Those that do crop up are mostly like new.

On the other hand, Warhol’s copy of Judy Garland’s soundtrack to A Star is Born is lovingly worn—its box half crushed, its grooves played out. Albums by early ‘50s doo-wop groups like the Coasters and the Orioles are similarly scuffed. And, above all, the cabaret singers and classical recordings have been played and played and played. Flipping through the titles, one would be hard-pressed to call Warhol a rock fan, nonetheless avant-garde.

“Warhol probably didn’t actually like rock music all that much,” says Wrbican. “There are stories of him being out all night at parties, with hip rock bands, but he would come home afterwards and listen to his opera tapes. I think he was just happy listening to that.”

Thursday nights at the Met

The old Metropolitan Opera House, in midtown Manhattan, was only a few blocks from Andy Warhol’s studio, yet in the Pop Art heyday of the 1960s it might as well have been on a different planet. At The Factory, Warhol Superstars Billy Name and Ondine played opera constantly—particularly the diva Maria Callas, beloved of the New York gay scene. But that might well have been where the relationship ended: Where The Factory was the “15 minutes” of celebrity and the fascination with the commercialism of Pop, the Met was the tuxedos and gowns of high society.

“The operatic tradition of audience-going—dressing properly, being at a society function—that would’ve still been very powerful in the 1960s,” says Christopher Hahn, general director of the Pittsburgh Opera. “It would’ve been very much the ‘Golden Horseshoe’ and ladies in tiaras and of the old families holding sway.”

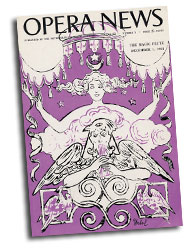

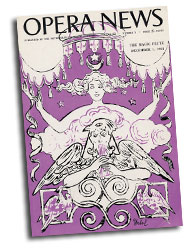

Cover illustration by Andy Warhol

depicting a scene from The Magic Flute.

Yet there, below the society-types whose box seats comprised the Golden Horseshoe row, and unbeknownst to his Factory accomplices, was Andy Warhol. As

Warhol Live shows, Warhol’s obsession with opera didn’t begin with his collection of reel-to-reel tapes and LPs of the great tenors and sopranos, nor had it ended with his illustrations for

Opera News in the 1950s. Throughout the 1960s, even as he attributed the operatic tones emanating from The Factory to his Superstars, it was Warhol who owned an annual Thursday night subscription to the Met.

“That’s something that he hid, in a way, that he was such a fan,” says Wrbican. “But in the 1950s, people going to the opera or to classical dance and ballet performances, they all knew him. That was before he developed his ‘Pop’ persona, when he had a bit more of a graphic designer persona, which was merged with the dance and opera worlds.

“Many of those people who knew him in the ‘50s say that if they did see him years later, after he started painting soup cans and such, he was very cold to them,” Wrbican says. “He had moved on from that part of his life, and you had to occupy a very special place to maintain a friendship with him.”

Even while Warhol was keeping secret his sophisticated, even high-brow guilty pleasure, its influence was apparent in his work—specifically, his search for Gesamtkunstwerk, opera composer Richard Wagner’s notion of a “total artwork.” It’s something he sought in multi-media events such as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI), and in his own life of integrated art, business, and society spaces such as The Factory and Studio 54. And it’s something he found, perhaps, in Maria Callas.

Emphemera culled from Warhol’s

famous Time Capsules.

In his essay for the

Warhol Live catalogue,

Warhol and Opera: Andy’s Secret, John Hunisak, a history of art and architecture professor at Middlebury, determines—from Warhol’s ticket stubs and the Met’s archives—that Warhol was present when Callas made her New York Metropolitan Opera debut in 1956. As Warhol sought that “total artwork,” he could probably imagine no better example than Callas.

“Suddenly, there was this meteor of extravagance, both in real life and onstage,” says Pittsburgh Opera’s Hahn. “She very seriously expounded the notion that opera was not just about the voice—she was such a fierce proponent that it was about the mix of drama and music, which was iconoclastic at the time, and viscerally exciting for audiences when they heard it.

“It doesn’t surprise me in the slightest that Warhol was an opera fan. The reason it came into being was that people became sick and tired of the division between painting or singing or theater or dance—it’s really a coming together of all those elements. Opera means ‘the works,’ and in modern jargon, it does throw the works on the stage. To people who are experienced particularly in one field, in opera they see that field illuminated in many different ways.”

“That appealed to him, that artifice,” adds Wrbican, “where you could sit in a very comfortable velvet lounge seat with a bunch of very elegant people and see this amazing thing on stage, and hear this incredible singing and music and get totally lost in that. And except for the velvet seats, it’s not that different from an EPI show, or even Studio 54—which might be a bit more sweating-to-the beats, but it’s acoustical and it’s visual, and it’s a total artwork.”

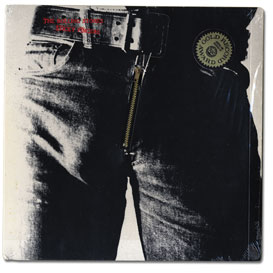

The zippable zipper on the cover of The Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers album helped make it one of the best-selling albums of its day while also becoming one of the most iconic images of 1970s rock. To a smaller, yet profoundly influential audience, it might’ve been Warhol’s peelable banana on the front of The Velvet Underground & Nico album, the first release by the avant-garde rock troupe Warhol managed in the late-1960s, that was the image of the decade. Others have cradled Warhol’s work through the covers of jazz albums for Blue Note and Prestige labels or in his drawings for classical recordings by composer Maurice Ravel.

The zippable zipper on the cover of The Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers album helped make it one of the best-selling albums of its day while also becoming one of the most iconic images of 1970s rock. To a smaller, yet profoundly influential audience, it might’ve been Warhol’s peelable banana on the front of The Velvet Underground & Nico album, the first release by the avant-garde rock troupe Warhol managed in the late-1960s, that was the image of the decade. Others have cradled Warhol’s work through the covers of jazz albums for Blue Note and Prestige labels or in his drawings for classical recordings by composer Maurice Ravel.

“Up until recently, most curators of Warhol shows were interested in painting, in visual art, and comparing this body of work with those of other artists,” explains Wrbican. “The people responsible for putting together exhibitions weren’t thinking quite as much about other media.”

“Up until recently, most curators of Warhol shows were interested in painting, in visual art, and comparing this body of work with those of other artists,” explains Wrbican. “The people responsible for putting together exhibitions weren’t thinking quite as much about other media.”  Not long after, Warhol created his first, and one of his most famous, art films.

Not long after, Warhol created his first, and one of his most famous, art films. Yet there, below the society-types whose box seats comprised the Golden Horseshoe row, and unbeknownst to his Factory accomplices, was Andy Warhol. As Warhol Live shows, Warhol’s obsession with opera didn’t begin with his collection of reel-to-reel tapes and LPs of the great tenors and sopranos, nor had it ended with his illustrations for Opera News in the 1950s. Throughout the 1960s, even as he attributed the operatic tones emanating from The Factory to his Superstars, it was Warhol who owned an annual Thursday night subscription to the Met.

Yet there, below the society-types whose box seats comprised the Golden Horseshoe row, and unbeknownst to his Factory accomplices, was Andy Warhol. As Warhol Live shows, Warhol’s obsession with opera didn’t begin with his collection of reel-to-reel tapes and LPs of the great tenors and sopranos, nor had it ended with his illustrations for Opera News in the 1950s. Throughout the 1960s, even as he attributed the operatic tones emanating from The Factory to his Superstars, it was Warhol who owned an annual Thursday night subscription to the Met. In his essay for the Warhol Live catalogue, Warhol and Opera: Andy’s Secret, John Hunisak, a history of art and architecture professor at Middlebury, determines—from Warhol’s ticket stubs and the Met’s archives—that Warhol was present when Callas made her New York Metropolitan Opera debut in 1956. As Warhol sought that “total artwork,” he could probably imagine no better example than Callas.

In his essay for the Warhol Live catalogue, Warhol and Opera: Andy’s Secret, John Hunisak, a history of art and architecture professor at Middlebury, determines—from Warhol’s ticket stubs and the Met’s archives—that Warhol was present when Callas made her New York Metropolitan Opera debut in 1956. As Warhol sought that “total artwork,” he could probably imagine no better example than Callas.