Summer 2009

|

||

Little Teenie and Big Teenie in a self-timed photograph (right) and Little Teenie today (above), inside Hamm’s Barber Shop in the Hill District with owner Walter Hamm in the background. Hamm, who’s been in business for more than 50 years, still displays photos Teenie took of him in the 1960s.“I wish Dad could see this. He worked so hard, and he didn’t get to see the fruition of his hard work.” -"Little Teenie" Harris“One shot instead of a gunshot—that’s definitely a slogan for our kids.” Alisa Hughes, Hill District resident |

An Equal Opportunity Lens

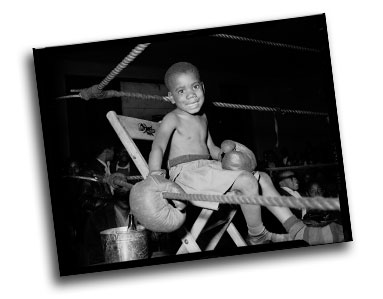

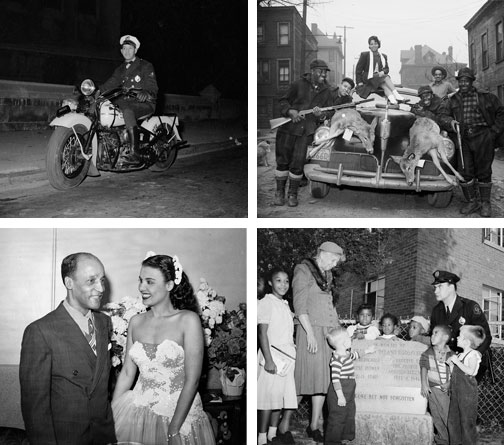

Charles A. “Little Teenie” Harris adored the father he was named after, the famous photographer who took photos of African Americans in the Hill District from the 1930s to the 1970s. Speed Graphic in hand, his father would rush off to cover news events for the Pittsburgh Courier or just walk along the street snapping photographs of everyday people. Father and son—dubbed “Big Teenie” and “Little Teenie” only when they were together —would develop the images in the Harris Studio at 2128 Centre Avenue in the Hill District. Decades later, Charles A. Harris is combing through some of those same images at the request of Carnegie Museum of Art, which purchased Teenie’s collection from the Harris family in 2001. The soft-spoken 81-year-old is the curator of Documenting Our Past: The Teenie Harris Archive Project, Part Three, opening July 18 in the museum’s Forum Gallery. Poring through thousands of his late father’s photographs has been bittersweet. “I wish Dad could see this,” says Harris. “He worked so hard, and he didn’t get to see the fruition of his hard work.” A retired statistics division manager with the Internal Revenue Service, Harris chose some images that have never been viewed by the public. In one shot, a group of African American hunters on Wylie Avenue surround a car, a deer carcass on one fender, a bear on the other. Another shows a young female tennis player in action. “When you think of the Hill District in the ‘40s, you don’t think of people going hunting, fishing, or playing tennis,” Harris says. “It is not the type of sports people associated with the African American community.” Visitors will also be treated to images that capture people at work, including a coal miner with a lunch pail, standing next to loaded pit cars, and a portrait of the first African American motorcycle policeman, Karl Jackson, who is also the cousin of Harris’ wife, Beatrice.  As guest curator of the upcoming Teenie Harris exhibition, Little Teenie saw many of his father’s images for the first time, including a photograph of his wife, Beatrice, at age 15 or 16. The pair grew up a block apart.When Harris looks at certain photographs, he says he can feel the presence of his father, who died in 1998. In one classic photo titled Little Boy Boxer, an unnamed child sits in a chair in the corner of the ring, his boxing gloves dwarfing his tiny body. A tear runs down his cheek, but he is trying to smile. “It is almost as if he lost and was crying,” says Harris, “and he looked down and saw my Dad with a camera and it made him smile. Snap. And then the picture is history. Many different conclusions could be drawn from this image; this is mine.” Of the thousands of his father’s photographs he’s seen over the years, it’s his favorite.

A teary-eyed boy boxer (Little Teenie’s favorite)Growing up TeenieOther images are plucked from Harris’ own childhood. One self-timed photo shows Little Teenie as a toddler in the lap of his adoring father. Another shows his younger brother, Ira (who went by his middle name, Vann), perched atop a table with his hand smashed into his first birthday cake. (Little Teenie was the only child from Teenie’s first marriage, to Ruth Butler; the photographer later married Elsa Elliott and they had Ira Vann, Lionel, Crystal, and Cheryl.) The birthday theme is interspersed throughout the show because Teenie would have been 101 this year.“One of the coolest things about this exhibition is that the son is the curator, the person who knew him best,” says Louise Lippincott, chief curator and acting co-director of Carnegie Museum of Art. “So the selection has a very particular, intimate sensibility to it. It is just fascinating. There is a personal meaning behind every photo that Little Teenie selected.” Numbering some 80,000 prints and negatives, the Teenie Harris Archive is the largest collection of Pittsburgh images by a single photographer. What’s more, it constitutes the largest photography collection by one person of one place in the African American community. “It provides a window into the mind and mood of the people—the expressions on their faces, whether they look alienated or happy, the way they stand,” says Laurence Glasco, a University of Pittsburgh history professor and a member of the museum’s Teenie Harris Advisory Committee. “It shows people who are remarkably positive and upbeat in their outlook. It is going to make us rethink our ideas of black life in the so-called bad years of segregation.” Like the previous two exhibitions of Teenie’s work hosted by the Museum of Art, captions won’t accompany the photographs; this is a rarity for museums, but is part of the point of these exhibitions. By placing notebooks within the gallery, the museum will encourage the public to identify the places and faces in the images, providing meaningful context to the collection. Cries of “Oh, that is my cousin” or “I know that man” were often heard during the earlier exhibitions. “It seems to me if you were around in Pittsburgh from the late 1930s to the 1970s, if you ever went to a club or a game or parade, chances are there might be a picture of you,” says Kerin Shellenbarger, a photo archivist who worked with Harris as he shaped the upcoming exhibition. With funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Shellenbarger and a staff of five catalogers and imaging technicians have been cataloging and digitizing the archive at a rate of about 150 images a day since the museum’s first exhibition of Teenie’s work in 2003. To date, the museum has scanned and cataloged nearly 60,000 images, many of which are available to the public on the museum’s website.  Teenie had an “equal opportunity lens” while capturing life in the Hill District: (L to R) police officer Karl Jackson, a group of hunters, Lena Horne and her father in the Stanley Theatre, and Eleanor Roosevelt in Terrace Village.Capturing the EverydayDapper and charismatic, Teenie Harris just had a way of putting his subjects at ease, making them forget the camera. He treated everyone with dignity, whether it was Lena Horne or an unknown laborer or a school kid.“He had an equal opportunity lens,” says his son. To that point, many photographs Harris selected highlight everyday people, including a group shot of teenage girls at Westinghouse High School, wearing plaid skirts and tops they had made for a social club. Harris’ wife Beatrice was a member of the club. Others highlight the famous and glamorous. Dazzling in a strapless sequined dress, Lena Horne is smiling at her father backstage at the Stanley Theatre. Another shot shows a playful Muhammad Ali carrying his mother. Some photos will be recognized by Harris fans from previous exhibitions, including an animated Eleanor Roosevelt talking to a group of children in 1946 during the dedication of a Franklin D. Roosevelt memorial in Terrace Village in the Hill District. While other photographers took photos of the First Lady posed with politicians, Harris notes, “Only Teenie got the pictures of her with kids.” Teenie Harris—nicknamed so when his aunt called him “teenie little lover” as a child—didn’t start out as a photographer. He worked for his older brother, William “Woogie,” a numbers baron and one of the first black millionaires in Pittsburgh. But fearful of arrest, Teenie wanted out of the numbers business. So, in 1938, he opened his own photo studio with $3,500 that Woogie gave him. Three years later, he joined the staff of the Courier and established himself as a star at one of the most influential black newspapers in the nation. Teenie Harris moved his family to Mulford Street in Homewood in the early 1930s, but he continued to work at the photo studio in the then-booming Hill District, “a city within a city,” as Harris recalls. The photographer taught his oldest son how to develop photos, including those with interracial subjects. The face of a black person would appear first, notes Harris. If the photo tech let the process continue until the white face appeared, the black face would bleed into an ink spot, a mistake white newspapers often made. The photographer’s son learned how to develop images so both races would come out clearly. But Big Teenie never gave Little Teenie a camera. And the son never had a desire to study photography. “There is only one Teenie Harris photographer,” he says. “Anyone else would have been a poor second.”

|

|

Also in this issue:

Robots R Us · Honoring Robotic Mettle · Diva Intervention · A Tribute to Our Donors · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Ellen McCallie · About Town: Teen Tonic · Field Trip: Branching Out · Science & Nature: Harnessing the Horse · Artistic License: Expanding View · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

In an upcoming exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art, the oldest child of legendary Pittsburgh Courier photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris tells his father’s story just as it should be—in pictures.

In an upcoming exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art, the oldest child of legendary Pittsburgh Courier photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris tells his father’s story just as it should be—in pictures. Help Document History

Help Document History