|

||

|

"Studying robots

is a way to study ourselves, that's what makes them so fascinating." - David Bourne, principal scientist at Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute

"What could be

cooler than robots? Dinosaurs are cool, but you can't build a dinosaur." - Henry Thorne, a Pittsburgh roboticist

|

Robots R Us

All they have, we have given them. They can do some things we can—play air hockey, vacuum the living room—and some things we cannot—hold pieces of red-hot metal or squirm through a 12-inch pipe. They may one day drive our cars and rake our leaves, maybe even grow our crops. They are robots, and for more than 30 years, many of these technological marvels have come to life right here in Pittsburgh. So it’s fitting that the city the Wall Street Journal once dubbed “Roboburgh” is home to the largest permanent robotics exhibit in the world. roboworld, Carnegie Science Center’s one-of-a-kind exhibit featuring more than 30 interactive displays featuring all things robotic, opens June 13 (with an exclusive preview for special friends and supporters June 7 and a members-only sneak peek June 10-12). Ron Baillie, the Henry Buhl, Jr., co-director of the Science Center, expects it to be a far-reaching draw. “It’s one of those topics, like dinosaurs or space exploration, that’s just as appealing to an 8- or 9-year-old as it is to someone who’s 75 years old,” says Baillie. “It’s really interesting to see a machine try to do what we humans do.” The exhibit is some four years in the making, and uses the expertise and robots of some of the world’s top robot entrepreneurs, academics, and universities, with a specific emphasis on the Pittsburgh region’s strength in all things robotic. It also will provide the first physical home for Carnegie Mellon University’s star-studded Robot Hall of Fame® (see Honoring Robotic Mettle), and give visitors a unique glimpse into the futuristic world of robotics.

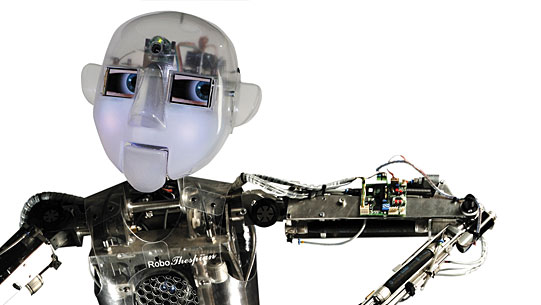

Andy, roboworld’s robot greeter.

If your image of a robot is C-3PO tut-tutting R2-D2, be prepared for some surprises. Robots are no longer the stuff of science fiction. They do a variety of unsavory jobs in the real world, like mine sweeping, cleaning nuclear reactors, and examining sewer lines. Robots are indispensable in manufacturing and packaging. Hospitals and the military are giving robots jobs that are repetitive or dangerous. Spurred by advances in computing power and artificial intelligence, scientists are developing machines that can play with autistic children, dance, and clean your kitchen. The robots in roboworld work, play, even chit-chat. Some make art. Others may look like the humanoid robots of popular science fiction—a metal contraption touting some kind of eyes, a head, arms, and legs. Others will resemble, well, toasters. “We’re provoking the question: what is a robot?” says Kim Amey, project manager for the $3.5 million project. That’s why the show is constructed around the three tasks robots complete like no other machine: thinking, sensing, and acting. “Do you need all these things for it to be a robot?” questions Amey. “If it can sense and act, but not think, is it a robot? If it can think and act, but not sense, is it a robot?” The machines in roboworld are indeed all robots—programmable machines that respond to sensory inputs like sounds, sights, and even changes in temperature. The 6,000-square-foot exhibit immerses visitors in the science of robotics, how these machines are used, and gives a taste of the ongoing debate about what role robots should play in our lives. It also probes why we are so fascinated by them. “Studying robots is a way to study ourselves, that’s what makes them so fascinating,” says David Bourne, principal scientist at Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute, a partner in the exhibit. “We have to think about how we think, how we see, smell, and touch, and how we put these things all together to make decisions. If we want to make a machine that does what we do, we have to really understand ourselves.”

At Work–And PlayIt’s no surprise that robots do a lot of our work. The term robot was popularized in 1921 by Czech playwright Karel Capek and is derived from the Slavic word robota, which denotes drudgery or any demeaning, monotonous labor.Today’s robots do what we couldn’t, or wouldn’t—or, given our druthers, probably just shouldn’t. “We focus on dirty, dull, and dangerous,” says Philip Johns of RedZone Robotics, a Lawrenceville firm whose robots navigate sewer lines, scanning for cracks and breaks. RedZone has also made robots that have been put to work in nuclear power plants and industrial storage tanks. “These are places where you’re better off taking a human out of the equation and having a robot do the work for them.” Visitors to roboworld will see RedZone’s Solo robot, which roams sewer lines as narrow as 8 inches in diameter. Solo is roughly the size of a very narrow skateboard—20 inches long by 4 inches wide. If it encounters an obstacle in a pipe, it will back up and try again three times before heading back. If one of its sensors reports that it’s going too fast or is tilting at too great of an angle, it will slow down. “You’re basically making a vehicle, putting a computer on board, and telling them to work together,” Johns says.

Students from Infinity Charter School get a sneak peek of the exhibit. Photos: Renee RosensteelOther worker robots will also be front and center, including Robot Rx, a robotic pharmacy device developed by Pittsburgh-based McKesson, and TUG, a robot made by another local company, Aethon, that delivers medicine, food, and materials in hospitals and nursing homes. (Aethon, McKesson, and many other companies donated robots for roboworld.) But, rest assured, there will also be plenty of time to play in roboworld. Visitors can shoot baskets with Hoops, the Science Center’s popular free-throw shooting robot, and compete against robots that play air hockey and foosball. Advances in robotic “thinking” have also made possible the advent of robotic artwork. Aaron, the Cybernetic Artist, draws pictures based on unique decisions it has been programmed to make. Lunar Rover, an art installation, uses sensors of crowd movement to guide a pair of robotic “legs.” Using one of the fastest robotic arms in the world, Sketch Robot replicates human-made drawings by placing tiny marbles on a table top. And if that doesn’t seem hard enough, the table top is spinning. Still other roboworld inhabitants will interact directly with the crowd. Visitors will meet Chatbot, a robot than answers questions; Pong, a robot that mimics facial expressions with sensors that can tell whether someone is happy, sad, or angry; and, of course Andy, the robot greeter named by the voting public prior to the exhibit’s opening. RoboburghThanks to its universities and a rich history of innovation dating back to its steel-making days, Pittsburgh has more robotics companies and academics than any other city in the United States, says Illah Nourbakhsh, an associate professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon University.His colleague, David Bourne, recalls seeing Pittsburgh for the first time in 1979, just as the region’s storied steel industry was declining. “The air was still yellow from the steel mills,” Bourne recounts. “But you could see it turning, the steel mills were going out, and something was going to have to fill that void, and robotics seemed the thing to do that.” Sure enough, Pittsburgh’s legacy as a cradle of robotic novelty was cemented by the opening of Bourne’s workplace, Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute, which burst on the scene that same year. It was the first of its kind in the country and has since produced a generation of innovators and spawned several local companies. Among them: Tartan Racing, the university’s unmanned vehicle research lab, has garnered national attention for winning driverless car races. The school’s robotics pioneer, William “Red” Whittaker, founder of Redzone Robotics, is leading a team in the $30 million Google Lunar X Prize to be the first to land an unmanned spacecraft on the moon. Given this backdrop, putting roboworld in “Roboburgh” was a no-brainer, says Baillie. “It’s one of those topics that’s natural for Pittsburgh,” he says. “We figured if somebody was going to do a major permanent exhibit on robotics, it ought to be here, and we ought to be the ones to do it.” R is for RobotAs fun as robots are to adults, they hold a special place in the minds of children. Robotics are a great way to get children interested in math and science, says Nourbakhsh, who has used robotics to teach middle school girls, and even kindergartners.“They represent innovation in a nice, physical, visceral way that attracts kids,” says Nourbakhsh, who’s also part of the Science Center’s advisory committee for roboworld. “They can see it and they can even play with it.” To that end, roboworld includes an activity center, where children—and their grown-ups—will be able to make their own mini-robot, devices they will design and assemble and that can move around a room. “We really hope people who leave the exhibit are just starting a conversation about robotics,” says Nourbahksh. “Hopefully, they’ll go home and talk about it over the dinner table and want to put some robots together in their living rooms.” The workshop will also feature a rotating array of robots and their inventors who will present works-in-progress. “The workshop is a chance to bring in brand-new stuff that maybe isn’t quite completed yet,” says Amey. “You could ask a roboticist questions and see in-person what they’re working on.” Among the first to be featured in the workshop: “snake robot,” a creation still Our Robots, OurselvesAbove all, roboworld’s creators say robots aren’t just useful or convenient—they’reirresistible to those who make them. “What could be cooler than robots?” says Henry Thorne, a Pittsburgh roboticist who built TUG, Aethon’s mobile hospital robot. “Dinosaurs are cool, but you can’t build a dinosaur.” When he was a kid, Thorne played with model airplanes, radio-controlled cars, and even made a homemade pinball machine. From there, it was a short leap to building robots. “With a plane, after you get it to do a loopty-loop, you’ve run out of things that it can do,” Thorne explains. “With a robot, there’s this sort of open-ended potential associated with it that’s so alluring. You can literally get it to do anything.” But do we really want it to do everything? “Honestly, with a lot of these questions—like ‘Will robots drive our cars?’—I don’t think technology will be a limiting factor,” says Mike Joyce, Jr., senior architect for Blawnox-based Integrated Industrial Technologies (I2T), creator of the software that powers roboworld resident Sketch Robot and a roboworld advisory committee member. “Most likely, it will always be driven by human laws, and human decisions. If someone gets hurt by a robot-driven car, who’s at fault?” Just as scientists grapple with these questions, so will roboworld. An interactive kiosk will ask visitors to key in answers to a variety of ethical questions such as “Should robots care for the elderly?” The machine powering the kiosk will then tally and display responses to the poll. “We really want people to think about these questions,” explains Amey. “Could robots become sentient? How much power should they have?” An ethos of endless tinkering, endless innovation, and endless questioning is certainly at the heart of roboworld. And that’s what its creators hope to impart to visitors, especially the young ones. “As toolmakers we’ve always wanted to extend, enhance, or grow our own capabilities,” adds Joyce, of I2T. “The first human to pick up a stick was trying to make their arm longer. Books increase our memory; horses allowed us to go faster. “We’re always trying to make things faster, more efficient. Robots are just that next step.” |

|

Honoring Robotic Mettle · An Equal Opportunity Lens · Diva Intervention · A Tribute to Our Donors · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Ellen McCallie · About Town: Teen Tonic · Field Trip: Branching Out · Science & Nature: Harnessing the Horse · Artistic License: Expanding View · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |