"John’s enthusiasm really rubbed off on me—he’s one of the reasons I became an entomologist."

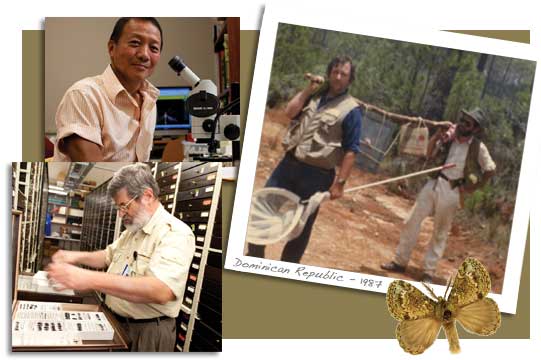

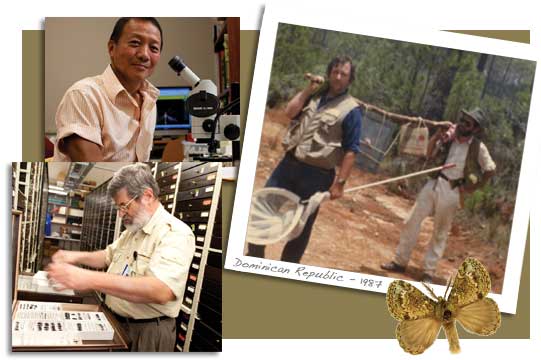

Chris Dietrich

Curator of Insects, Illinois Natural History Survey

|

|

Insect Appellant

The unconquerable, sometimes incorrigible, John Rawlins loves his bugs. And he’s determined to use them to help the world diagnose and treat some of

its worst environmental ailments.

By Justin Hopper

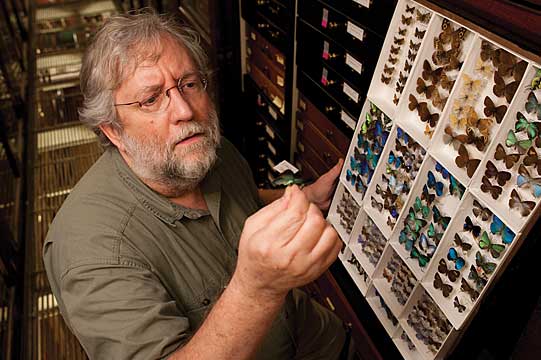

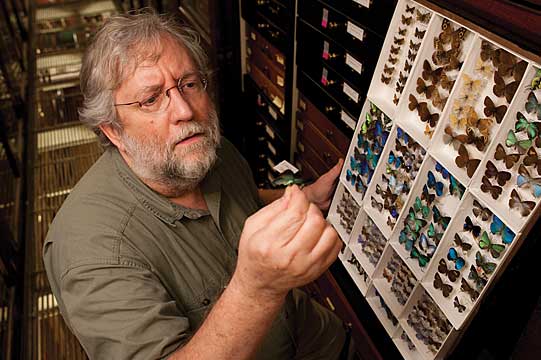

John Rawlins strokes at his wispy, whitening beard, his voice hushed to a near-whisper as he describes Pic Macaya, a mountaintop along the western arm of Haiti on the island of Hispaniola. There’s real drama in that voice, like a storyteller sharing ghost stories around a campfire. But this storyteller is sitting in a windowless hallway of Carnegie Museum

of Natural History’s Section of Invertebrate Zoology (IZ), part of the maze of bug cabinets and stacked boxes that double as office and research space for this quirky band of bug scientists.

Everything’s dramatic when John Rawlins, longtime head of the IZ section, talks bugs. Everything’s dramatic when John Rawlins, longtime head of the IZ section, talks bugs.

“The connections and origins of this lost land—it’s relictual; it’s left over from the past,” Rawlins says of Haiti’s mountainous region, where he sees so much potential for new discoveries of really ancient bugs. “Many of the bugs on the island are riffraff, blowing around in the Caribbean wind. Go to Puerto Rico, Cuba, and you’ll find the same bugs as in the lowlands of Hispaniola.” He decrescendos again, cocking his head forward like he’s ready to share a secret. “But you go into these mountains, turn over a rock, and there’s a little wingless moth, or a flightless beetle, and their ancestors have been there for millions of years.”

Rawlins leans back slowly, point made.

“You give me three weeks up on Macaya,” he says, “just three weeks—me, an old man —and we’re gonna find some wild stuff.”

Rawlins has just finished a grant proposal to the National Science Foundation to hopefully fund research trips to Haiti, and damn if he isn’t excited. To him, Haiti represents the great unknown—a place unexplored by previous entomologists, and a “biodiversity hotspot,” which Rawlins believes is home to large numbers of never-before-seen species.

He has every reason to be excited: The first wave of his team’s exploration of Hispaniola—a 20-year study of the Dominican Republic—resulted in specimens and data that have already been used in more than 70 scientific papers by researchers around the world.

Never Enough Bugs

Nothing pleases Rawlins more than the idea of being surrounded by brand-new bugs.

Rawlins has spent his adult life surrounded by insects, and nearly 25 years at the Museum of Natural History, where the bug collection contains more than 11 million prepared specimens and 20 million more unprepared—everything from Mongolian crane flies, to moths collected in Africa just after World War I, to a bevy of bugs from outside the museum’s doors in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood.

Rawlins’ mission statement is simple: It’s never enough. Driven by what he and his closest colleagues see as an unprecedented time of environmental change, Rawlins believes it’s their mission to keep getting out into the field to collect more samples. His strategy is to do so in some of the world’s most devastated and under-surveyed regions, such as the Caribbean and Africa, before those regions’ species are destroyed.

Rawlins and long-time colleagues Chen Young and Bob Davidson, both of whom pre-date Rawlins in the IZ section, are entomologists in the intricate field of systematics—the study and classification of lineages whose features differ among species. So, for example, they can determine whether a beetle just discovered in Pennsylvania is one whose eating habits make it a danger to local forests or if it’s just a harmless species that merely looks a lot like the destructive variety. The difference could be the most miniscule variation in the beetle’s body makeup, or its morphology.

Rawlins explains that by knowing about a bad beetle’s lineage, a systematist can suggest a remedy to the destruction it could cause. Perhaps its closest related species is susceptible to a certain locally available predator that could be used to help fight the invading beetles. And since there are so many insects, of so many species, it’s a science with a unique angle on the planet’s biodiversity. Rawlins explains that by knowing about a bad beetle’s lineage, a systematist can suggest a remedy to the destruction it could cause. Perhaps its closest related species is susceptible to a certain locally available predator that could be used to help fight the invading beetles. And since there are so many insects, of so many species, it’s a science with a unique angle on the planet’s biodiversity.

Theirs is a struggle that has led Rawlins and his colleagues on an unorthodox and workaholic path of discovery, as well as to a kind of success that’s rare in today’s tough research environment. While many IZ departments have been cutting staff, Rawlins’ group has expanded into its own eclectic collection of bug lovers—about 13 people, including database specialists and scientific preparators, admired by bug enthusiasts the world over. They’ve done it, Rawlins says, by finding “new uses for old bugs.”

It’s a plan that works because of Rawlins’ other skill: inspiration. When John Rawlins tells you why we need to pay attention to bugs, he ceases to be Dr. Rawlins, entomologist and becomes John Rawlins, preacher man.

photo:Josh Franzos

Rawlins credits a few other eccentric bug men for his own entomological fervor. And in a kind of homage to them, he’s built his own flock of bug believers at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and beyond.

The Homeland

Rawlins points at the computer screen as Google Earth’s satellite-view map of the western United States zooms in, closer and closer, on the eastern part of Oregon, near the Idaho border. He traces the outline of Morrow County; a little closer and he’s lovingly running his forefinger along the lines of a canyon. Rawlins points at the computer screen as Google Earth’s satellite-view map of the western United States zooms in, closer and closer, on the eastern part of Oregon, near the Idaho border. He traces the outline of Morrow County; a little closer and he’s lovingly running his forefinger along the lines of a canyon.

“This here, this is one of my favorite places—Rock Creek,” says Rawlins, smiling. “And see, these are the canyons of the Home Place (his childhood home). And this clearing here”—a house is now clearly visible on the screen—“those are the relics of the ranch house, what we called the Upper Place.”

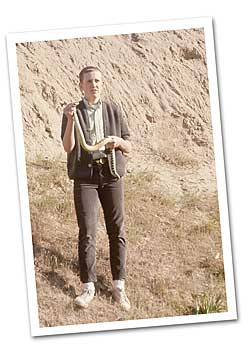

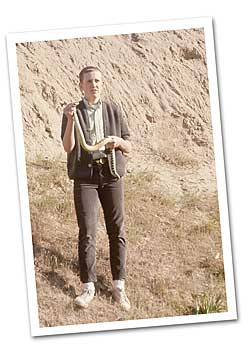

John Rawlins’ first love was snakes, not insects.

He’s shown here at age 15.

Unlike the claims of so many small-town natives, the sheep ranch on which Rawlins was raised truly is in the middle of nowhere. A few miles from the Upper Place is the town of Hardman, Oregon, where Rawlins’ uncle was once mayor of some 30-odd citizens. (Hardman is today listed by ghost-town enthusiasts as ‘Class D’—a ghost town, but with a few remaining residents.) There, on the extensive acreage of the family’s ranch, Rawlins inherited his love for zoology, the branch of biology that focuses on the structure, function, behavior, and evolution of animals. During the Great Depression, his father “rode the rods” to Oregon—stowing away beneath a train’s boxcars and eventually becoming a somewhat eccentric rancher. Unlike his neighbors, he had studied wildlife biology at Oregon State University and collected exotic livestock breeds for fun.

In the 1960s, Rawlins followed in his father’s footsteps and earned his bachelor’s degree at Oregon State, eventually moving on to graduate school at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. It was there that his first zoological interest—snakes—would be remolded by his relationship with a charismatic mentor.

“I decided to change my program because I met this old man at Cornell, Dr. John Franclemont,” Rawlins recounts. “I was very different from most bug people; they tend to start very early, very young. I’m a latecomer—I was already 25 years of age by the time I got to the first bug.”

Perhaps even more important than sharing his scientific knowledge (it was the Cornell professor who turned Rawlins onto Lepidoptera, otherwise know as moths and butterflies), Franclemont shared his contagious excitement for entomology with Rawlins, who has since inspired his own fair share of bug lovers to experience similar metamorphoses.

Charismatic Collecting

Tim Tomon was an ecology student at the University of Pittsburgh when he began a work-study job in Carnegie Museum’s IZ section—not, by any means, his first choice for a research gig. Tim Tomon was an ecology student at the University of Pittsburgh when he began a work-study job in Carnegie Museum’s IZ section—not, by any means, his first choice for a research gig.

“I used to sit in that room, surrounded by piles of insects, watching those guys interact,” Tomon says. “John’s a charismatic guy—it’s hard not to get excited about this stuff when you talk to him. Just being there, I became fascinated with the whole thing.”

Tomon is now the forest entomologist for the West Virginia Department of Agriculture, putting his degree in systematic entomology to good use monitoring invasive and dangerous agricultural pests.

Chris Dietrich, curator of insects at the Illinois Natural History Survey, had a similar experience. In the early 1980s, Dietrich was studying at Pitt as a pre-med student when he joined the section as a part-timer. He was soon joined by Rawlins, who first came to Pittsburgh specifically to use the museum’s famous Lepidoptera collection—considered one of the best in the world—for his post-graduate work. Besides the Lepidoptera collection, Dietrich points out that the Carnegie collection is also important and unique for its holdings of South American and Caribbean insects.

“I was inspired by those guys and what they were doing—going off to all the far corners of the world collecting all the weird bugs,” he recounts. At the time, Rawlins, Davidson, and Young were already becoming known for their daring adventures collecting in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, the Far East, and Central Africa. “John’s enthusiasm really rubbed off on me— he’s one of the reasons I became an entomologist. He has a gift in that area that not many people have.

“There’s a tendency for museum people to be anti-social; our work requires large amounts of uninterrupted time,” Dietrich adds. “But it really helps to have those skills to convey the importance of this work—not just to the general public but to get funds for your department.”

By the time Rawlins returned to Pittsburgh in 1986 to take over as head of the museum’s IZ section, his enthusiasm had blossomed into genuine fervor. Aided by fellow true believers in the value of systematics, including Davidson and Young, the section began to reformulate a new purpose—from quiet collector to proactive player on the biodiversity research stage.

“We have to do this balancing act based on what’s here and what the collection needs, but also what the world needs,” says Bob Davidson. “We’ve been criticized for collecting bugs even though we’ve got millions of things here that aren’t properly cataloged. But the world's going extinct faster than we can collect it. This isn’t the generation to tidy up your nest. This is the generation to get out and get the samples!”

Chen Young and Bob Davidson at work in the “bug rooms.” At right, Davidson (back) and John Rawlins collect insects in the Dominican Republic in 1987. Photos: Josh Franzos

Endangered Science

Triage. It’s not a word you’d expect to hear among the glass-paned drawers of carefully spread butterflies and pinned beetles. But it’s a word that comes out of John Rawlins’ mouth frequently.

“Triage” collecting: It’s when you leave the safety of the office for the wilds of Africa, South America, the Caribbean—regions where the diversity of living species is matched only by the decimation being caused by environmental change and human encroachment.

From their early days together in the IZ section, Rawlins, Young, and Davidson have stayed true to this bold approach to collecting, foregoing those places where so many entomologists made their names, and careers, in favor of places that were endangered, and plenty dangerous to humans, too.

“Our studies started out with us just liking bugs,” says Rawlins. “We’re eccentric—Chen, Bob, and I who have been here the longest, and the rest of the staff by inference. We’re a little weird; we’re stubborn, and not very compatible to the mandates of our field. It’s not rebelliousness, but we do make our own decisions about what we value.

“We wanted to take the collection from being forgotten in the world of entomology; and, to do so, we had a little mission—and yeah, it sounds a bit like Star Trek: ‘To collect where others are not documenting.’”

Rawlins explains that while the museum has a great historical collection of bugs from Africa, South America, and Jamaica, it was the “hotspots” of those regions, where collecting wasn’t happening, that most interested him and his team.

They knew that filling in gaps would be tough, expensive, nasty work, since they were attempting to go where others feared—or just didn’t have the guts and determination—to tread. Places like the Congo, where the group was collecting in 1995 when civil war broke out. But they also knew that their collecting strategy could make the Museum of Natural History’s collection a vital player on the world entomological stage and do something of real historic importance within their field. Their triage work could have practical applications throughout the global community, especially the parts of the world facing ecological decimation.

“These governments have small amounts of conservation resources,” says Rawlins. “If there are 30 areas with problems, they can’t protect all 30—maybe six. So, which ones? The bugs will tell us.”

To put their plan into action, Rawlins and his team established the Biodiversity Services Facility (BSF), through which the IZ section has begun selling its services to clients—primarily the federal government—to help identify the potential agro-economic dangers, sometimes even the bioterrorist threat, of invasive insect species.

The BSF is largely a repurposing of the tools and skills within the department, and BSF-commissioned work has helped fund the department’s expansion. Rawlins says he envisions a day when the BSF becomes the go-to identification resource for all of the world’s insects.

Today, besides the potential grant for a trip to Haiti to continue their groundbreaking research on Hispaniola, Rawlins and company have their fingers crossed about a potential job with the Northeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies

to create an online database and information portal for data on rare and endangered

invertebrate species (especially insects). It’s the kind of service that the IZ section—

with its varied specialists and connections throughout the entomological world—is particularly adept at providing.

Rawlins believes that his own species— systematic entomologists—are themselves endangered, largely because of a refusal to acknowledge the value placed on just this kind of work.

“The information that systematists provide as a discipline is largely given away,” says Rawlins. “Even the leaders in the field don’t understand how it’s necessary to value what you do. When you don’t value your own knowledge, you keep in the same tracks, and there’s nothing driving the development of new uses for old bugs.” “The information that systematists provide as a discipline is largely given away,” says Rawlins. “Even the leaders in the field don’t understand how it’s necessary to value what you do. When you don’t value your own knowledge, you keep in the same tracks, and there’s nothing driving the development of new uses for old bugs.”

To Rawlins, Haiti is a perfect example of that potential.

“I believe that there is a way to help Haiti and its people that has to do with the bugs,” he says. “Haiti has such hopeless environmental conditions that, more than any other nation, it’s the testing ground—it’s us tomorrow. If we can save biodiversity in Haiti, we can save it anywhere. And this could be driven by bugs. When it comes to environmental change, bugs are the canary in the coal mine.” |

Everything’s dramatic when John Rawlins, longtime head of the IZ section, talks bugs.

Everything’s dramatic when John Rawlins, longtime head of the IZ section, talks bugs.

Rawlins explains that by knowing about a bad beetle’s lineage, a systematist can suggest a remedy to the destruction it could cause. Perhaps its closest related species is susceptible to a certain locally available predator that could be used to help fight the invading beetles. And since there are so many insects, of so many species, it’s a science with a unique angle on the planet’s biodiversity.

Rawlins explains that by knowing about a bad beetle’s lineage, a systematist can suggest a remedy to the destruction it could cause. Perhaps its closest related species is susceptible to a certain locally available predator that could be used to help fight the invading beetles. And since there are so many insects, of so many species, it’s a science with a unique angle on the planet’s biodiversity.

Rawlins points at the computer screen as Google Earth’s satellite-view map of the western United States zooms in, closer and closer, on the eastern part of Oregon, near the Idaho border. He traces the outline of Morrow County; a little closer and he’s lovingly running his forefinger along the lines of a canyon.

Rawlins points at the computer screen as Google Earth’s satellite-view map of the western United States zooms in, closer and closer, on the eastern part of Oregon, near the Idaho border. He traces the outline of Morrow County; a little closer and he’s lovingly running his forefinger along the lines of a canyon.  Tim Tomon was an ecology student at the University of Pittsburgh when he began a work-study job in Carnegie Museum’s IZ section—not, by any means, his first choice for a research gig.

Tim Tomon was an ecology student at the University of Pittsburgh when he began a work-study job in Carnegie Museum’s IZ section—not, by any means, his first choice for a research gig.

“The information that systematists provide as a discipline is largely given away,” says Rawlins. “Even the leaders in the field don’t understand how it’s necessary to value what you do. When you don’t value your own knowledge, you keep in the same tracks, and there’s nothing driving the development of new uses for old bugs.”

“The information that systematists provide as a discipline is largely given away,” says Rawlins. “Even the leaders in the field don’t understand how it’s necessary to value what you do. When you don’t value your own knowledge, you keep in the same tracks, and there’s nothing driving the development of new uses for old bugs.”