Fall 2009

Fall 2009|

“Through video conferencing we get a chance to bring the world to the classroom without putting students on buses.” - Joe Cataline, Linden School District, New Jersey |

Virtual Field Trip

Coming this fall to schools near and far:

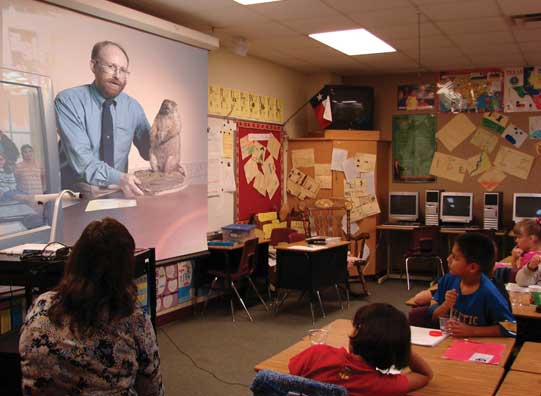

Patrick McShea visits an elementary classroom, remotely.Between them, Patrick McShea and Sue McJunkin have taught science and social studies in classrooms in 26 states, Canada, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic. They've developed lesson plans for all 12 grades as well as kindergarten. What’s even more remarkable: They did it all in just seven years and without ever leaving Pittsburgh. The dynamic duo from Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s distance learning program has traveled into more than 200 school districts via the Internet and real-time, full-motion audio and video. Through the power of a technology that is quickly becoming more accessible to schools, large and small, McShea and McJunkin put on their own brand of show and tell, using actual natural history objects as educational tools. And these aren’t just any objects—they’re part of the massive collection of the country’s fifth largest natural history museum. Think real “stuffed animals” or taxidermy mounts, real dinosaur bones, and everything from bats, groundhogs, and owls, to insects, rocks, and minerals. The program, which got its start in 2002, is fully interactive. Not only can students and instructors see and hear one another, they can ask each other questions. And this past November, just in time to meet increased demand and expanded programming, the distance learning program moved operations from temporary quarters in the museum’s Earth Theater to a new roomy, soundproof videoconferencing studio within the museum’s Center for Museum Education. McShea thinks that, at times, the technology even trumps in-person learning. “With our different cameras there are things I can show a classroom better than if I was actually there standing in front of them,” says McShea. “For instance, a vampire bat's skull is very small, about as big as your fingernail. If I held it in my hand and tried to show students, it would be difficult to see. But with the use of our video cameras, we can blow it up to cover the entire television screen.” Another plus of the remote program: the involvement of the museum’s esteemed scientists. In fact, one of the program’s goals for this upcoming school year is to expand its “Meet the Scientist” offerings into a twice-a-month format. The idea is to give schoolchildren behind-the-scenes access to the museum, albeit remotely. Already on tap for fall: Anthropology Curator Sandra Olsen will talk about her work on horse domestication; Collection Manager Suzanna McLaren will spotlight the museum’s mammal collection and its importance in ongoing research around the world; and Trish Miller of Powdermill Nature Reserve, the museum’s field station in the Ligonier Valley, will talk about the ongoing research of the migration routes of the golden eagle. In the future, when a scientist makes groundbreaking news, such as a new discovery, distance learning audiences might even be among the first to hear the details—straight from the scientist’s mouth. Carnegie Museum of Natural History is just one of about 160 institutions that offer videoconferencing programs to schools through the Center for Interactive Learning and Collaboration (CILC). Competition is steep as the museum vies for audiences with zoos, science centers, aviaries, medical centers, performing art centers, and, in some cases, corporations. Last year, the museum presented about 300 programs, compared to just 25 in 2002. The secret? Gold star status from teachers. “Carnegie Museum has received gold star rankings for multiple programs,” says Ruth Blankenbaker, executive director and founder of the CILC. “That's phenomenal. It's unusual. Getting a gold star on teacher evaluations means that they met the objective, engaged the students, there’s evidence of learning, and that the teacher rated it an exceptional program.” Last winter, Joe Cataline, educational technology specialist for Linden School District in New Jersey, welcomed McShea into a third grade classroom, virtually, to talk about groundhogs. “He had a wealth of information, more than our teachers knew about the subject. He presented big murals, taxidermy, and photos. The students were able to see what the feet and claws of a groundhog look like,” says Cataline. “We’re an urban school district and with budget constraints and the economic situation it gets harder and harder to take students places. Through video conferencing we get a chance to bring the world to the classroom without putting students on buses.” Even better news for young learners: technology is getting cheaper and more accessible. Within the last year, 35 of 42 school districts in Allegheny County alone installed videoconferencing equipment. “It’s safe to predict that videoconferences will become more widely used by teachers as instructional tools, even as the technology involved with them changes,” notes McShea, an educator with Carnegie Museums for 24 years. “Within the museum, I hope to help more of our staff, both educators and scientists, become comfortable in front of the cameras so we can do a better job of visually sharing our resources with audiences who might otherwise never benefit from our collections.” It’s obvious that McShea and McJunkin love what they do. After all, notes McJunkin, a former teacher in the Churchill School District (now Woodland Hills), she no longer has to worry much about grades or discipline. “I get to do the fun and exciting stuff,” she notes, “and be the expert.” Programs are 45-60 minutes and cost $125, with discounts available for multiple bookings. Programming is available for schools with IP- and ISDN-based videoconferencing systems. For reservations and updated program schedules, call 412.622.3292 or email idea@carnegiemnh.org. |

Also in this issue:

Poster Boy · The Whales' Tale · Insect Appellant · Destination Pittsburgh · Presidentís Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Jason Busch · About Town: The Art of Change · Science & Nature: Robots Rule · Artistic License: Word Play · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |