Fall 2009

|

||

“The idea has always been to make images that break through the clutter. I want to get people’s attention and make them question what they’re seeing.” - Shepard Fairey |

Poster Boy

Coming to The Warhol this October is the first solo show by Shepard Fairey, Andy Warhol legatee and the world’s most influential street artist, who’s reinvigorating questions like, When does a poster stop being design and become a work of art?

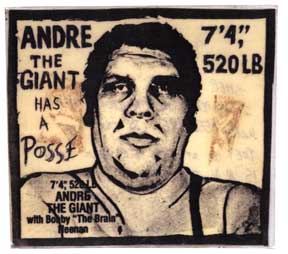

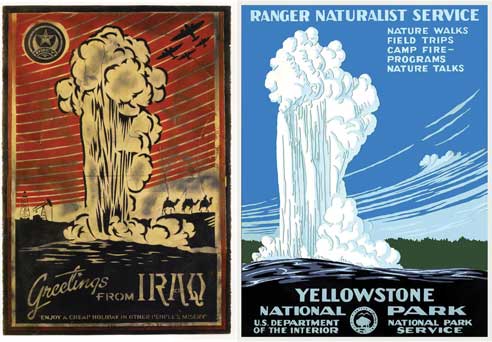

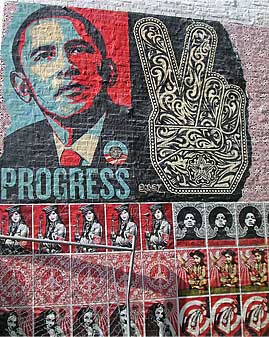

You may not know his name, but you certainly know his work. Shepard Fairey is the street artist who created the red, white, and blue “Hope” portrait of now-President Barack Obama. The one that helped define an historic campaign—from the outside in—and was described by The New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl as “the most efficacious American political illustration since Uncle Sam Wants You.” The act—and the image-appropriation controversy that followed—catapulted the Los Angeles-based hipster to nearly instant fame. Now outrageously in demand, the 39-year-old has been labeled everything from the godfather of modern urban art, to the artist of his generation, to sell-out and thief. In other words, people tend to love or loathe him. Before all the fuss, Fairey was best-known as the hard-working—even obsessed—punk-influenced, cult graphic artist who, ever-so-slyly, illegally plastered his “Obey Giant” stickers and posters—adorned with the face of the 1970s French wrestler Andre the Giant—on countless lamp posts, boarded-up buildings, and prominently placed billboards from coast to coast and around the world. “The idea,” Fairey explains, “has always been to make images that break through the clutter. I want to get people’s attention and make them question what they’re seeing.” Today, fresh off the wildly successful debut of his first solo museum show at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in Boston—and his 15th “poster bombing” arrest, which came, incidentally, as he was about to enter the exhibition’s opening party—Fairey is firmly planted in two, often contradictory worlds. He continues sacrificing work to the street, a possible liability in the world of fine art. He also increasingly churns out high-paying creative for those he once railed against, such as corporate giants Pepsi, Honda, and Saks Fifth Avenue, threatening his street cred. Traditionally conservative Bostonians first embraced him, making his 20-year survey the ICA’s most popular exhibition in its 73-year history. Then they literally ran him out of town. When his show, Shepard Fairey: Supply & Demand, arrives at The Andy Warhol Museum this October, one can only wonder—how will Pittsburgh respond?  The street artist, who’s a husband and father of two young girls, is incredibly prolific, often called obsessed. “You know I’m diabetic, so I’m probably going to live a lot shorter amount of time than most people, so I’m making the most of it,” says Fairey.STICKING TO ITIt all started with a sticker.As a young skater-punk in Charleston, South Carolina, Fairey started buying skateboarding stickers. They were rad, cheap, and badges of honor. Unable to find punk-rock stickers, he learned to draw the logos of his favorite bands and, using his Mom’s copying machine, he Xeroxed his first graphic onto sheets of Crack ‘n’ Peel labels. Instant stickers. “It sounds crazy,” admits Fairey, “but stickers changed my life.”  During the summer of 1989, after his first year at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Fairey was working at a local skate shop when he stumbled upon a picture of pro wrestler Andre the Giant (André René Roussimoff of The Princess Bride fame). Using it to teach a friend how to make a stencil, he jokingly added the phrase “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” in one corner and the wrestler’s tip-the-balance stats—“7’4”” and “520 LB”—in the other. Just like that, the first Giant sticker was born. During the summer of 1989, after his first year at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Fairey was working at a local skate shop when he stumbled upon a picture of pro wrestler Andre the Giant (André René Roussimoff of The Princess Bride fame). Using it to teach a friend how to make a stencil, he jokingly added the phrase “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” in one corner and the wrestler’s tip-the-balance stats—“7’4”” and “520 LB”—in the other. Just like that, the first Giant sticker was born. The original Andre the Giant stencil, created as a joke in 1989.“Once the first domino fell,” wrote Fairey in the Supply & Demand catalogue, “I was addicted and had my sight set on world domination through stickers.” He’s come awfully close. Described by Fairey as “simultaneously sinister and goofy,” he sticker- and poster-bombed (street slang for wheat pasting) that face all over Providence, then on to New York, Boston, and beyond. Along the way, he branded Andre with the Orwellian tag “Obey,” as in obey whom? Why? And says who? He subsequently swung open a dialogue about who owns public space, and before he knew it, his campaign went old-school viral—pre-Internet: just Fairey, friends, and fans spreading Andre one street corner at a time. Fairey estimates that he’s sacrificed between 7 to 10 million stickers to the street and another 200,000 posters. WARHOL DISCIPLEFairey’s one-man show follows the curve of his career, in his bold, signature red, black, and off-white palette. His “back catalogue,” as he calls it, includes his earliest stickers and stencils, works on skateboard decks, images of punk stars, and photos of his most dramatic “Obey Giant” conquests—sky-high water towers included. The exhibition, organized by the ICA, also highlights his more recent and deftly detailed fine-art images exploring the iconography of power. His large, stenciled images on canvas mimic both the scale and in-your-face impact of his street work.“There’s a lot more depth and layering, and there’s time, a lot of time spent on these pieces,” says Fairey. “There’s a layering that makes it feel like it’s a surface that’s had a prior life, where things just happen, like on the street. It’s how I bring the organic nature and the chaos of the street into a gallery.”  But much like Andy Warhol, who Fairey names as one of his biggest influences, along with punk rockers the Sex Pistols and Black Flag, Fairey has fans and critics who are equally passionate about the legitimacy and implications of his work. Suddenly, the artist who insists that we “question everything” is the subject under the microscope. But much like Andy Warhol, who Fairey names as one of his biggest influences, along with punk rockers the Sex Pistols and Black Flag, Fairey has fans and critics who are equally passionate about the legitimacy and implications of his work. Suddenly, the artist who insists that we “question everything” is the subject under the microscope. “My work, and this show in particular, has created a lot of interesting debate,” says Fairey. “For instance, whether I agree with some of the more aggressive, vocal Bostonians or not, I still think it’s cool to have the issues out on the table. That’s what my work had always been about, to question everything.” These days, Fairey’s work is just as likely to be seen as the focus of a blue-chip marketing campaign or the cover art of a chart-topping album as on a blighted building. Obey Giant—20 years in the making—has sprouted into a lucrative empire. Obey Giant Art offers limited edition posters that sell for about $45 online; design firm Studio Number One, operated by Fairey and his artist-wife, Amanda, nabs clients like Virgin and Adidas; and Obey Clothing sells in Urban Outfitters and other major retailers. Like Warhol and Keith Haring before him, Fairey masterfully mixes art and business and blurs the lines of fine and commercial art, infusing his daring graphic design with propaganda spirit. “I’m not necessarily just trying to emulate Warhol,” says Fairey, “but I’m definitely feeling like, well, Warhol did it, so, hey, it’s okay. There are no rules about how to be an artist because Warhol has already broken most of them.” Perhaps the pair’s closest parallel is how they got their start. Both Warhol and Fairey studied at prestigious art schools, Warhol at Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh and Fairey at the technically rigorous Rhode Island School of Design. Both majored in illustration and graphic design.  Fairey likens image appropriation to a band covering another artist’s song. His Greetings from Iraq was inspired by the 1930s Works Projects Administration artwork promoting national parks.“That’s one thing that Warhol proved in an extraordinary way, that there are great smarts in that business,” says Warhol Director Tom Sokolowski. “It wasn’t just, here’s this genius, Warhol. He learned a lot from brilliant advertising guys. A good Coca-Cola ad has more effect in getting someone to do something than the Mona Lisa does.”  Some of Fairey’s critics, especially fellow underground artists, claim he’s sold out by doing commercial work. “What does it mean when, as a street artist, he starts making new products?” asks Sokolowski. “Does that mean he still can’t have verve? Does that mean he can’t make agit-prop (political propaganda) just because he has a few dollars? Or does that mean that he’s now well-heeled enough, shrewd enough that he can make even better stuff?” Some of Fairey’s critics, especially fellow underground artists, claim he’s sold out by doing commercial work. “What does it mean when, as a street artist, he starts making new products?” asks Sokolowski. “Does that mean he still can’t have verve? Does that mean he can’t make agit-prop (political propaganda) just because he has a few dollars? Or does that mean that he’s now well-heeled enough, shrewd enough that he can make even better stuff?” Still, the Associated Press and a handful of independent artists have called Fairey a serial plagiarist, ripping off of Soviet Propaganda, ‘60s rock posters, and everything in between. “There are images out there that everyone has access to, and to put your own spin on them is a form of language,” says Fairey, admittedly accustomed to this kind of criticism. “The role of art, to me, isn’t always making something that no one’s ever seen before, but commenting on things people have seen before. Different people have different ways of interpreting art. I think art needs to address the sort of realities of the culture we’re living in, which is that images aren’t hard to come by, but making commentary on them that adds new meaning is still not easy and still is valuable.” Surprisingly, Warhol, the king of appropriation some 40 years ago, was only sued once during his lifetime, not for his Elvises or Campbell’s Soup Cans but for something as mundane as a photograph of blossoms, lifted from a magazine and used as the basis for his Flowers. Not surprisingly, Fairey’s show is lined with Warhol appropriations. Using long-handled brushes and wheat paste, Fairey and his team put up murals on an empty building along Bigelow Boulevard in Polish Hill last month. Photos: Renee Rosensteel

BANNED IN BOSTON If Sokolowski has his way, when President Obama and the cadre of world dignitaries descend upon Pittsburgh later this month for the G-20 Summit, Shepard Fairey and his buckets of wheat paste will be waiting. If Sokolowski has his way, when President Obama and the cadre of world dignitaries descend upon Pittsburgh later this month for the G-20 Summit, Shepard Fairey and his buckets of wheat paste will be waiting. As an extension of Supply & Demand, Fairey has been granted a number of “legal walls,” as he describes them, to post public art around Pittsburgh, as he did in Greater Boston. In Pittsburgh for the first time last month, Fairey already left his mark in Garfield, Lawrenceville, Downtown, and the North Side. The hope is that all of his public work—a mix of new and recycled images—will go up in advance, or possibly during, the Summit, well before The Warhol show’s October 17 opening. “The windmill image that I did recently for MoveOn is something that I put up in Pittsburgh because of the Summit,” says Fairey, referencing his patriotic-looking Clean Energy for America, now found on the side of Rosa-Villa Cafe on the North Side. “There’s also a global warming image that I’m working on right now. Pittsburgh could be the first to see it.” The big question is if—or more likely how much—he’ll risk on his famous extra-curricular activity now that he’s on probation from his most recent charges in Boston. Originally facing 34 felony charges with a maximum penalty of 87 years in jail, he pleaded guilty to one count of defacing property and two counts of wanton destruction of property in exchange for all other charges being dropped. Under the plea deal, he paid $2,000 to a graffiti-busting group and can no longer carry “tagging” materials—such as stickers, posters, or wheat paste—in Boston. The arrest came three days after he failed to appear in court on a charge of placing a poster on a Boston electrical box nine years earlier. “If I were arrested in Pittsburgh, Boston could theoretically extradite me,” explains Fairey. “It’s not likely that would happen, but it’s something I have to be concerned about. I’m lucky that my career has evolved to the point where I have other ways to get my art out there.” But won’t he miss the adrenaline rush? “Yeah, I think the best thing for me to do,” adds Fairey, laughing, “is keep quiet on all that stuff, what my plans are.” YES WE CAN |

|

Also in this issue:

The Whales' Tale · Insect Appellant · Destination Pittsburgh · Presidentís Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Jason Busch · About Town: The Art of Change · Field Trip: Virtual Field Trip · Science & Nature: Robots Rule · Artistic License: Word Play · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

“I think it’s fair use in the way that I’ve interpreted it,” Fairey has said in countless interviews about the subject. “And if you look at Pop art over the last 50 years, I think it reinforces that assertion.”

“I think it’s fair use in the way that I’ve interpreted it,” Fairey has said in countless interviews about the subject. “And if you look at Pop art over the last 50 years, I think it reinforces that assertion.”