|

||

|

This Friesian horse’s name is Flying Dutchman.

|

The Horse

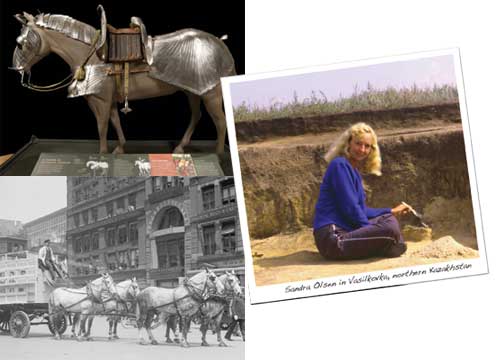

Coming to Carnegie Museum of Natural History in February, an expansive new traveling exhibit is sure to get us all thinking about man’s extraordinary, enduring, and perhaps even predestined relationship with the stately horse. Sandra Olsen is talking horse sense. Sitting in her office in a barely noticeable cement-block building in Pittsburgh’s East End, surrounded by horse-related art, books, and research, Olsen explains why the horse is the second-most important factor in mankind’s progress throughout history. “Aside from the development of the stone tool, no other thing, plant, or animal has played a bigger role in human achievement,” says Olsen, curator of anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “They were the first form of rapid transit. Empires were built and conquered on the backs of horses. They changed geopolitics from Asia to Europe, the Americas, and beyond. Dogs, cattle, sheep, and pigs were domesticated earlier, but the horse’s versatility made it far more valuable.” After studying man’s most indispensable four-legged friend for nearly three decades, Olsen welcomed the opportunity to share her insights as a co-creator of a comprehensive and compelling new exhibit that explores the relationship between horses and humans. Simply and elegantly titled The Horse, the show will arrive at Museum of Natural History on February 28 and run through May 24, 2009. “I can’t wait for people in Pittsburgh to see this exhibit,” says Olsen. “It’s one of the most exciting shows I’ve ever seen or worked on in my career.” One Sweet Ride Now showing at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, which produced the exhibit, The Horse takes a page or two from Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibit as it explores the horse’s affect on its surroundings and vice versa. Now showing at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, which produced the exhibit, The Horse takes a page or two from Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibit as it explores the horse’s affect on its surroundings and vice versa. Divided into six sections, The Horse breaks out of the gate fast with a stunning high-definition video of a galloping steed. Shot at 1,000 frames per second, the clip captures the majestic beauty, strength, and grandeur of the animal—attributes that have captivated humans since early man first painted their figures on cave walls. The pace continues at full stride throughout a thorough retelling of the equine’s epic history, from the horse’s earliest days on the planet to its enduring bond with human beings that’s still evolving. To better understand the animal’s physical mechanics, a large-scale video and interactive computer display offers an inside look at a life-size, moving horse. A sprawling 220-square-foot diorama depicts various horse species dating back 10 million years in what is now Nebraska. Artistic representations and artifacts capture the mystique of horses from the Paleolithic age, some 30,000 years ago, to the present. A full suit of 16th-century German horse armor reveals how man employed the beast to wage war. Closer to modern times, a hulking 19th-century New York City horse-drawn fire engine shows a more beneficial use of the animal’s potential. One interactive station even provides visitors a chance to test their strength in terms of “horsepower.” “This is an extraordinary exhibit,” says Ross MacPhee, the show’s co-creator and curator of mammalogy for American Museum of Natural History’s division of vertebrate zoology. “It covers 6,000 square feet with approximately 30 different interactive stations. The broad division of the show is between evolution and biology versus the horse-human relationship, which encompasses all kinds of cultural aspects such as domestication, warfare, commerce, sport, status, and our ongoing relationship with horses.” When The Horse rides into Pittsburgh, it will be its second leg of a worldwide tour that will continue on through North America and the Middle East. The global itinerary is fitting for a show that explores how one animal affected so many different cultures in so many different ways—and heavily relies on holdings from museums both near and far. “When you’re doing a show like this, you don’t have all the objects in your own collections that you’d like to put on display,” says MacPhee. “That’s especially true with this exhibit because it’s heavily given over to many different cultural and historical matters, not just bones and biology. So we had to make a lot of loan agreements with other institutions to amplify the show.” Perhaps no “loan” was more vital to the show than Olsen, MacPhee’s first choice to co-curate the show. “I’ve known Sandra for more than 20 years,” says MacPhee. “I’ve long known of her interest in zooarchaeology and horses. So when we were in the development stage at our museum, it was obvious that we needed an expert to talk about the anthropological and cultural aspects. Sandra did a great deal of work in developing her ideas in the domestication section of the exhibit. In addition, she turned to her colleagues in horse studies to supply us with all the contacts and bibliographies you could want from a good collaborator.”

Humans have relied on horses for transportation, to wage war, and for their sheer strength. Above: Some 10 million years ago, up to a dozen species of horses roamed the Great Plains of North America. These relatives of the modern horse came in many shapes and sizes. ©AMNHD. FinninTaming the HerdThough it might be difficult to consider where we’d be—quite literally—without horses as part of our history, they no longer play an essential part of most people’s daily lives. Yet, a little more than a century ago, America’s city streets were teeming with working horses, not to mention the average 45 pounds of manure and two gallons of urine each animal left behind each day. In rural areas, horses supplied the power to help farmers plow fields and reap the harvest. Until the advent of the mass-produced, affordable internal combustion engine, horses drove the world’s economy, a fact mostly forgotten today. Olsen’s contributions to The Horse carry visitors back to a time more than 5,000 years ago, when humans first imagined how important a role the animal could play in their daily lives. While humans and horses have shared the planet for millions of years, Olsen’s work in the central Eurasian country of Kazakhstan reveals what may be the earliest traces of humans domesticating the animal, around 3300 B.C. Her study of the Botai people, who settled in a region that is now northern Kazakhstan, shows signs of a meat-based diet that relied 90 to 95 percent on horse flesh. While a predominantly horse meat diet was not altogether surprising in that region, where horse remains a dietary staple, Olsen’s research uncovered evidence that the Botai in fact raised the animals for food instead of hunting them.

“Aside from the development of the stone tool, no other thing, plant, or animal has played a bigger role in human achievement.”

- Sandra Olsen, curator of anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural HistoryTheir settlements consisted of up to 150 adobe houses, arranged along avenues. Generally, horse hunters followed herds on foot and lived in small, temporary encampments, explains Olsen, noting that she also discovered the presence of heavy horse bones, such as the pelvis, at the site, suggesting they were killed in or near the village. Because of the considerable weight of such bones, hunters often stripped them of meat before leaving them behind at a kill site. But one of her most telling finds, says Olsen, who has studied the origins of animal domestication since the late 1970s, was the remains of fence posts in a circular pattern that suggests a corral—as do heavy deposits of phosphorous and sodium that indicate high concentrations of horse manure and urine within that area. Not to mention strong indications that the Botai may have relied on mares’ milk to provide essential vitamins lacking in their meat-laden diet. MacPhee points to milking as evidence of Botai progress in domesticating the horses because, as he states, “you just don’t walk up to a wild mare and pull on her teat without getting kicked in the head.”

The Enduring BondAmong the more fascinating components of The Horse is a video of three people whose relationships with horses are a nearly everyday experience. One is a New York City mounted policeman who recently retired from the force. Because the bond between him and his horse was so strong, his horse retired with him. Another segment explores how a young girl on a western cattle ranch views her horse as a pet, a “worker” on the ranch, and an “athlete” that performs with her in riding competitions. The third storyline focuses on the therapeutic benefits of horseback riding for youngsters with severe physical, mental, or emotional difficulties. The City of Pittsburgh no longer maintains a horse force, but you’ll find a few steeds in the stables of the Allegheny County mounted police. Sergeant Joe Sotak says the county horses are mostly trotted out for parades and special events such as the recent Super Bowl celebration and Major League Baseball All-Star Game. He does, however, remember a time when the detail would ride downtown during the Christmas season and the reactions of holiday shoppers. “An officer on a horse is definitely an awesome presence,” says Sotak. “You’re riding so high above the crowd that people show a lot of respect. And as far as patrolling a crowd, one cop on a horse is like 20 on foot.” Just as mounted cops aren’t a common sight locally, city youngsters don’t have much opportunity to grow up on ranches. Still, 18-year-old Melissa Esposito, of Coraopolis, has been riding horses since before she started pre-school. Today, she’s a student at the Community College of Allegheny County and climbs atop her favorite horse at least a couple times a week. For her, riding is like a “conversation that only sometimes needs words.” “There’s a special trust between you and a horse,” says Esposito. “A simple action can let her know that you want her to turn or stop without saying anything. And horses always have been able to comfort me in ways that words can’t equal. It’s a special bond that takes time to build and lasts for a long time.” For 6-year-old Kody Conley, horseback riding is an extraordinary experience. Born with seizures that caused severe brain damage, Kody eventually underwent surgery that removed the right side of his brain, a procedure that left him unable to speak and with no control of the left side of his body. Three years ago, his grandparents, Randy and Robert Scanlon, enrolled Kody in therapeutic riding classes at Ford’s Stables in Indiana Township. “Kody’s been riding now for three years,” says grandmother Randy. “And it’s not just a matter of him sitting on a horse while someone leads it around a ring. The volunteer staff helps Kody learn how to control the horse and perform special tasks. The riding has helped him improve his balance, and he can give a few verbal commands to his horse. But the best part is to see him on his horse. You can see it in his eyes how proud he is to sit up straight and be in control. He might not be able to walk or talk like other kids, but on the horse, he feels special because he feels normal.”

Artist Deborah Butterfield created this sculpture from Hawaiian ohia wood and then cast it in bronze.

Grooming The HorseOne thing, for certain, is that The Horse is no typical exhibit. By foregoing a chronological review of the horse’s—and our own—place in the world, the show more coherently examines the interweaving roles horses and humans play in each other’s existence and development. It’s an approach that required an unusual amount of dedication for all to complete.

One thing that MacPhee hopes visitors gain is a greater appreciation for the animal and its role in human history. “The first thing people have to remember is that the relationship between humans and horses isn’t over,” says MacPhee. “They continue to be a presence. It’s a very different presence than it was a century ago, and certainly much different than thousands of years ago. But it’s important that people realize that the relationship humans have had with horses is the most important one we’ve ever had with a domesticated animal.” |

|

Darwin’s Big Bang: 150 Years Later · Paging Doctor Darwin · 1958 · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Now Showing · Face Time: Eric C. Shiner · Artistic License: Inside a Fantastical Mind · About Town: A Wild Weather Adventure · Science & Nature: All Hail the Telescope · First Person: Experiencing Life on Mars, Together · Another Look: Andy Warhol's Time Capsules

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

It doesn’t take a kick in the head to realize that while its days as a beast of burden, transport, or war are mostly in the past, the horse continues to find new and possibly even more spiritual ways to strengthen its relationship with humans.

It doesn’t take a kick in the head to realize that while its days as a beast of burden, transport, or war are mostly in the past, the horse continues to find new and possibly even more spiritual ways to strengthen its relationship with humans.

“The American Museum of Natural History doesn’t do things the easy way or take shortcuts,” says Olsen. “From its earliest stages to the opening of the exhibit, we worked for about two years to develop The Horse. And the results are worth it.”

“The American Museum of Natural History doesn’t do things the easy way or take shortcuts,” says Olsen. “From its earliest stages to the opening of the exhibit, we worked for about two years to develop The Horse. And the results are worth it.”