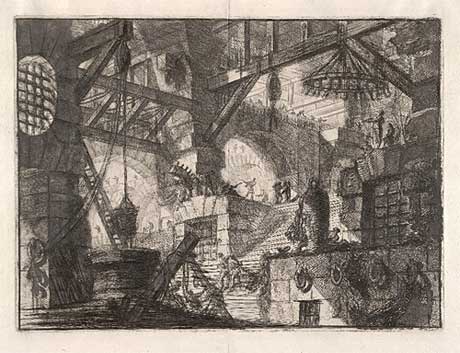

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Italian (1720-1778), The Well, 1761, gift of Kenneth Seaver

Inside A Fantastical Mind

A collection of work by master printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi, currently on view at Carnegie Museum of Art, investigates the line between architectural observation and the imagination.

By John Altdorfer

As a trained architect, Giovanni Battista Piranesi only saw one of his “great ideas” ever spring from the drawing board to reality—even with the backing of papal patron Pope Clement XIII. Yet 230 years after his death, the failed architect-turned-master-printmaker still manages to fascinate and inspire writers, filmmakers, and artists with his mysterious and, at times, seemingly mad etchings of prison settings and ancient Rome.

Now on display through February 15, 2009, in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Works on Paper Gallery, Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Architecture and the Spaces of the Imagination explores the fantastical, macabre, and often bewildering etchings that catapulted the artist to a position of prominence among his peers and the European public during the mid to late 18th century. While his etchings of Rome’s ancient ruins earned Piranesi considerable wealth, the exhibition’s main focus is the artist’s captivating Imaginary Prisons (Carceri d’invenzione) series, a collection of prints that is both arresting and liberating in its depiction of confinement and punishment.

Darkly foreboding, the detailed images reveal interior scenes of over-lapping archways and befuddling stairways that seem to lead nowhere. Dwarfed by their gigantic surroundings, the human figures—both captive and captor—seem trapped in an inescapable world of inhumane cruelty and despair. Though easy to imagine as embellished renditions of actual prisons, the nightmarish scenes are strictly the offspring of Piranesi’s fertile mind.

“These images depict completely fictitious settings,” says Amanda Zehnder, assistant curator of fine arts and the show’s organizer. “There are no known real architectural or prison references for these prints. And they have created a huge scholarly debate on why Piranesi created them. Even though he wrote constantly, Piranesi did not leave an explanation about why he chose prisons as a subject.”

While an artist’s statement would have provided significant insights, Drew Armstrong, assistant professor and director of architectural studies at the University of Pittsburgh, says the quality of Piranesi’s imagination and his incredibly sophisticated graphic techniques more than compensate for the lack of explanation.

“His work is so powerful and evocative that it creates vivid impressions that continue to inspire a variety of artists today,” says Armstrong. “Designers and architects still analyze his compositional and architectural techniques. His influence remains strong.”

Indeed, Piranesi’s widespread and enduring influence marks the work of Lord Byron as well as modern science fiction movie directors. Among those possibly inspired by Piranesi is M.C. Escher, whose “impossible constructions” include lithographs of waterfalls that replenish themselves in an infinite loop and a pair of hands that appear to be drawing each other. Edgar Allen Poe is said to have based his classic tale The Pit and the Pendulum on Piranesi’s prison etchings.

The son of a master builder, Piranesi studied as an architect under his uncle before traveling to Rome to work as an artist. While there, he created his first vedute, or views, of the city’s ruins and other landmarks, which earned him early recognition and success. Widely described as temperamental and difficult to work with, Piranesi was courted by the city’s most prominent citizens and Europe’s most influential artists because of his renowned printmaking skills.

Tirelessly dedicated to his art, Piranesi continued to create—according to legend—up to and including the day he died. Though the 25 Piranesi prints in the Museum of Art collection merely scratch the surface of the artist’s lifelong output, they represent the depth of quality in the museum’s collection of works on paper, which Zehnder says numbers in the thousands.

“The Piranesis, like other works on paper in our collection, are rotated for display,” says Zehnder. “They can’t be on exhibit for more than about three months at a time without risking further deterioration. And because of the fairly large size and extensive detail of the Piranesis, we are exhibiting fewer pieces than usual so that they have room to breathe, so to speak, on the walls.”

In development over a period of two years, the Piranesi show called for staff to pay special attention to pieces that are hundreds of years old. In some cases, Zehnder and her team rematted the prints and built special frames to hold the larger works. To heighten the prints’ visual effects, museum staff also repainted the walls of the Works on Paper Gallery.

Along with works from Piranesi’s 18th-century friends and colleagues, the show features five Clyde Hare photographs of H.H. Richardson’s Allegheny County Courthouse in downtown Pittsburgh. The photos capture interlacing stairwells and intersecting arches that seem to be straight from the mind of Piranesi, which is one of the goals.

“I hope viewers come away with an overview of who Piranesi was,” says Zehnder. “I think they’ll gain an appreciation of his skills and range of styles as a printmaker. In his views of Rome, he demonstrates a precise, detail-oriented style and in the Prisons series, his style was more expressionistic and emotional than you might expect from an artist of his time. And, I hope they come away with an understanding of Piranesi’s expressed belief that artists can and should demand great license in creative expression.”

|

Winter 2008

Winter 2008