To learn more about Darwin, don’t miss historian Janet Browne’s February 9 talk as part of the Drue Heinz Lecture series at Carnegie Music Hall. For tickets, call 412.622.8866. To get a schedule of local Darwin-related activities around town, visit www.duq.edu/darwin2009.

|

|

Darwin's Big Bang: 150 Years Later

By Julie Hannon

When trying to wrap one’s head around the heady topic of biological evolution, the trick may be to not get too caught up in the past. At least not initially.

“Instead of saying the way things came to be is evolution, we can now say the way things are is evolution,” says John Rawlins, head of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s section of invertebrate zoology. “The way things came to be is a story of origins; you think that’s in the past, and that’s a neat story. But how does it affect me today?”

Two hundred years after his birth, Charles Darwin and his scientific theory of evolution by natural selection still has scientific minds spinning, is still raising

eyebrows, and continues to influence the way the modern world views its past, present, and future. The fact is, without a clear understanding of the principles and processes of evolution, we couldn’t produce many of our staple foods, fight off invasive species, treat infectious diseases, search for new ways to treat human genetic ailments, or develop new drugs.

The power of evolutionary biology gives us a kind of crystal ball for the care, stewardship, and understanding of the diversity of life. And natural history museums are the stockpiles from which we draw a lot of that knowledge.

“Very often, the good that is done is because we’ve built this infrastructure of information for living things,” says Rawlins, who studies the vast diversity within the insect world. “When emergencies happen in the environment, when an invasive species strikes, when there is a need to understand why a species is either reproducing too much or going extinct, it basically comes down to the need for information and context, and often that need is relatively rapid.” Museum collections and the research of museum scientists—which are all about tracing the origins and relationships of varying species—are often crucial in fulfilling that need, Rawlins adds.

Stockpiles of Evidence

The applications of evolutionary biology are everywhere, and quite often, in the oddest of places.

When federal authorities turned up a disastrous agricultural pest along the outskirts of southern Miami this past fall, they speed-dialed Rawlins, an internationally renowned moth expert. What happened next unfolded like a fine-tuned military maneuver. After all, millions of dollars of American agricultural crops were in the direct line of fire.

During a routine U.S. Department of Agriculture survey, the government had captured the enemy: a type of moth destructive to corn, wheat, and soybean crops, commonly known as the old-world armyworm or cutworm. So the Feds called out the big guns—Rawlins included—to divide and conquer, which in this case meant running traps, sorting the samples, and identifying the captives. The question was: Were there more where that came from?

By way of FedEx, thousands upon thousands of dead moths arrived on Rawlins’ doorstep. Were they or weren’t they, as Rawlins refers to the invasive species, “tiny little terrorists?” “Thankfully, no,” says Rawlins, noting that he did confirm that the Feds had indeed captured one of the old-world moths initially, setting into motion this elaborate course of action. But luckily, no more were discovered. Disaster averted, at least for now.

What Rawlins did uncover was a third kind of closely related species from the Caribbean, one the Feds in Florida had been misidentifying for years. That particular insect has become so abundant that scientists predict it could very well cause its own share of problems in the not-so-distant future. Rawlins was able to identify it because, situated among Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s massive 21-million-specimen collection, rests another of its distant kin.

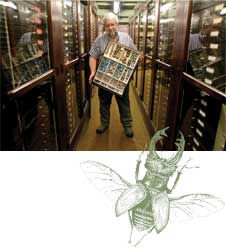

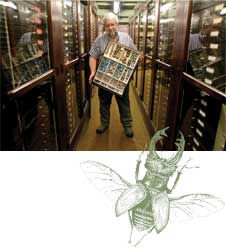

“Natural history museums are like libraries lending little unread volumes—the bugs, the fossils. They’re the driving force, the stockpile of data not yet observed by man”

- John Rawlins, head of Carnegie Museum of Natural History's section of invertebrate zoology. Photo: Sean Donnelly/Tribune-Review

A Dangerous Idea

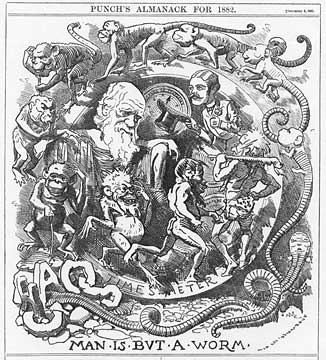

While Darwin is heralded as the “father of evolution,” the history of modern evolutionary science predates him.

By 1800, European naturalists had already collected and carefully studied scores of plants and animals, and even classified similar species in groups. A few bold thinkers, including Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Erasmus Darwin, Charles's grandfather, were among the first to speculate that species evolved at least 50 years before Darwin published the pioneering On the Origin of Species in 1859.

Lamarck saw that many animals seemed to have developed useful adaptations, but he couldn’t come up with a coherent explanation for how it happened. He suggested that the giraffe got its long neck from constantly reaching upward for food. But a key question dogged him: Could such a change be passed on to offspring?

“Obviously a father lifting weights doesn’t produce a muscular baby,” says Chris Beard, the Mary R. Dawson chair of vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “Darwin’s real contribution was natural selection—the how.”

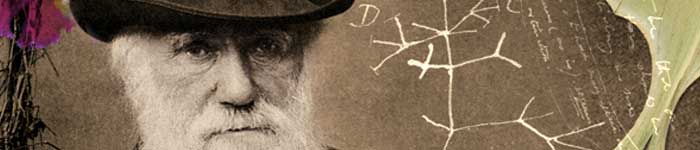

What Darwin achieved was nothing less than explaining the complexity and diversity of life. He did it by revealing a process called natural selection, commonly known as the survival of the fittest (a term coined later by philosopher Herbert Spencer, not Darwin).

Darwin saw in nature that all species exist in populations, and individuals in a population are different—so there’s variation among individuals. All species, he reasoned, produce far too many offspring for them all to survive, so those with traits that give them a competitive edge—they’re faster, or perhaps best able to camouflage themselves from predators, or best able to withstand drought—live longer and produce more similarly well-adapted offspring.

Over long periods, this process leads to significant changes in size, shape, strength, color, and behavior among descendants of a species, and the “fit” organisms dominate. “It is a contest,” Darwin wrote, and “a grain of sand turns the balance.”

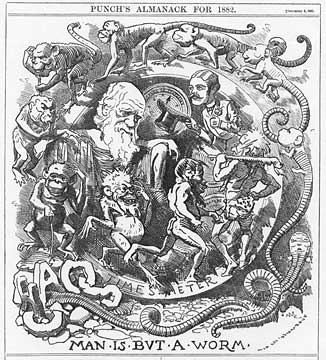

Darwin quickly realized that the same rules had to apply to humans. “It is absurd to talk of one animal being higher than another,” he wrote in one notebook; in another, “Monkeys make men.” But he knew his ideas would be considered an almost sacrilegious challenge to the world as everyone knew it, so he sat on them, building his evidence—for 21 years.

An unlikely and reluctant revolutionary, Darwin was shy and unassuming. Enamored with the natural world since his boyhood days of collecting beetles, he first studied to be a doctor at the urging of his father. When he only half-heartedly applied himself, his father told him, “You care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family.” He then tried a career as a clergyman, also encouraged by his father, before finally answering the call to natural history.

“His family’s wealth and connections afforded him many opportunities others would not have had,” notes Beard. By far the most life-altering came at age 22, when Darwin was invited on a trip around the world aboard the HMS Beagle.

For five years, the Beagle surveyed the coast of South America, leaving Darwin free to explore the plants, animals, geology, and fossils of the continent and nearby islands, including the Galapagos. He filled dozens of notebooks with his observations about the jungles of Brazil and the eruption of Mount Osorno in Chile. In his scribbles about marsupials in Sydney, he wondered why there were a whole different set of mammals in Australia.

Darwin earned more than his sea legs on the long, expansive voyage. He grew from a novice observer to a master analytical thinker, finding patterns in much of what he saw. He collected thousands of specimens, which he sent back home to London for further study. This work established him as a well-known naturalist, and eventually led him to realize that all living things are in some way related.

Like Confessing a Murder Like Confessing a Murder

In the end, Darwin did share his secret with a select few, including fellow scientist Joseph Hooker, a young botanist who had studied the plants Darwin sent home from the Beagle. Darwin wrote to Hooker that it was “like confessing a murder.”

Then, suddenly, in 1858, he was forced to confess to the world—or risk getting scooped. In a letter to Darwin, fellow naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace sketched out the same ideas that Darwin considered his own, seeking his reaction and help. Darwin was stunned. But Hooker and geologist Charles Lyell, knowing their friend had penned an essay outlining the very same ideas 15 years earlier, urged Darwin and Wallace to co-present at the Linnean Society in London, the world’s oldest biological society. Wallace agreed, and Darwin—finally—had his day.

“One of the cool things about science, and this happens over and over again even today, is that more than one person can have the same idea,” says David Lampe, professor of biology at Duquesne University and the driver behind the school’s annual Darwin Day activities each February, which is being expanded to a year-long celebration in 2009 in honor of Darwin’s 200th birthday. “If the scientific method is working, then the same observations and facts should draw different people to the same conclusion.”

While Darwin may have lost out on his opportunity to single-handedly introduce the world to the concept of natural selection, it was his published work that would truly rock the scientific community. He quickly published On the Origin of Species—all 490 pages of it—just one year later, gaining immediate and lasting notoriety.

“It was a completely transformative publication in the history of science,” says Beard, “and it transformed biology almost overnight. It was basically a matter of how fast you could read the book.” “It was a completely transformative publication in the history of science,” says Beard, “and it transformed biology almost overnight. It was basically a matter of how fast you could read the book.”

It sold out of stores the first day and caused a firestorm of discussion not just in Britain but around the world. The scientific debate was especially lively; but then, in an incredibly short time, the principle of evolution by natural selection would simply become part of the scientific vernacular, crucial to every scientist’s daily work.

“Evolution is what makes the modern practice of medicine scientific. It explains why a particular drug therapy that works in lab rats might also work in humans.”

- Chris Beard, the Mary R. Dawson chair of vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Death, Taxes, and Evolution

For an ongoing conservation project in Australia, Cynthia Morton, head of botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, is extracting DNA from an endangered plant from the Zieria group found mostly in the eastern part of Australia, and developing “relationship trees,” or blueprints of its genetic material.

“The Australian government wants to spend $30,000-$40,000 to save it,” explains Morton. “But we scientists said hold on—there are 20 species of Zieria considered endangered, and this particular species has the same genetic makeup as the plant over the hill, so maybe it’s not the best plant to save. There’s only so much conservation money to go around. We can’t save everything but we can and need to be smart about what we target. That’s what this research is about.”

That Morton and her fellow museum scientists—most of them self-described “naturalists,” just like Darwin—can play such a pivotal role in this kind of decision-making is par for the course, says Beard. Evolutionary biology is that important.

“Perhaps it’s most obvious in paleontology because we literally study the physical evidence of the evolution of life on earth in the form of fossils,” explains Beard. “But our biologists who study the end result of that long history of evolution will tell you, hey, I can collect bugs from Haiti, but if I don’t interpret them from an evolutionary

perspective, nothing makes sense. It’s nothing more than a big stamp collection otherwise.”

Thanks to evolutionary biology, the museum’s expansive holdings are, in fact, priceless, Beard adds. “They’re of huge scientific interest because of the evolutionary context that the Darwinian revolution placed upon them.”

But the reality is, while nearly everyone links biological evolution to Darwin, his science often gets eclipsed, or lost in translation to the public, because of the controversy that surrounds it. It’s a controversy that scientists say unjustly pits Darwin against God and the literal interpretation of the Bible, stirring a decades-long debate that, according to some, has resulted in a sub-par science education in our country’s schools. But the reality is, while nearly everyone links biological evolution to Darwin, his science often gets eclipsed, or lost in translation to the public, because of the controversy that surrounds it. It’s a controversy that scientists say unjustly pits Darwin against God and the literal interpretation of the Bible, stirring a decades-long debate that, according to some, has resulted in a sub-par science education in our country’s schools.

Most scientists today note that Darwin was unjustly accused of pitting

science against God.

“Evolution is taught unevenly because curriculum at the high school level is controlled locally,” says Lampe, noting there are no standardized tests that require students to have a clear understanding of evolution. “In Great Britain, for example, there are country-wide standards, so you learn the fundamentals no matter what. Here in our public schools, it’s basically a free for all. State standards are standards, but that doesn’t mean they’re going to be taught. It’s up to the local school board.”

According to a recent Gallup poll, 45 percent of responding United States adults agreed that “God created human beings pretty much in their present form at one time within the last 10,000 years or so.” Only 37 percent of those polled were satisfied with allowing room for both God and evolution—that is, a divine initiative to get things started and evolution as the creative process.

“I would encourage people to ask themselves this basic question,” Beard says, as if in response to those polled: “Why are biomedical researchers conducting experiments on lab rats? It’s not because they’re trying to cure diseases in lab rats. It’s because they think that understanding the basic biology of lab rats also tells them something about human biology. But unless rats and humans shared a common ancestor at some point in the distant past, there is no logical reason to expect rat biology to tell us anything meaningful about humans. Evolution is what makes the modern practice of medicine scientific. It explains why a particular drug therapy that works in lab rats might also work in humans. Why else would we be so obsessed with lab rats?

“Bottom line: Death, taxes, and evolution are the three things that are absolutely guaranteed to occur. No matter what else happens.”

The Stakes

Only at the closing of On the Origin of Species did Darwin talk specifically about human origins, for the same reasons many biology teachers steer clear of it today: fear of public backlash. It wasn’t until 12 years later that he published his follow-up book, The Descent of Man.

“I get the students who are pharmacy majors, the physical therapists, physician’s assistants,” says Lampe. “At the beginning of the semester, I give them a survey to find out what they know about evolution, and there’s mass confusion that pretty much mirrors that of the public at large.”

Botanist Cynthia Morton runs out recently collected DNA samples on a gel inside the museum’s Fisher Molecular Lab.

“ There’s only so much conservation money to go around. We can’t save everything but we can and need to be smart about what we target.”

- Cynthia Morton, head of botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Photo: Mindy McNaugher

For scientists, the controversy is not about whether evolution is taking place; it’s about why so much of the population rejects these well-found scientific facts—facts that are the cornerstone of all biology and medicine.

“We are handicapping our students by not teaching them the most fundamental idea in all of biology,” says Beard. “More and more of the American economy is contingent upon research and development, basic scientific advances that can be leveraged as economic growth. Biomedical research is a perfect example. It’s not an esoteric debate about philosophy and religion. It has practical and economic implications.”

Despite U.S. court rulings forbidding public school teachers from teaching explicitly religious alternatives to evolution, one in eight high school biology teachers still presents creationism as a scientifically valid alternative, a Penn State University study concluded this past May. It also found that most biology teachers spend five hours or less on evolution.

If Beard, Rawlins, Morton, and their colleagues have anything to do with it, this severe deficiency in science education will change some day. In the meantime, they’ll continue to help piece together the real-world, practical applications of evolution for everyone’s benefit.

A case in point: Beard, an expert on primates, has given lectures to OB-GYNs about the evolution of childbirth, and he’s currently partnering with a world-renowned orthopedic surgeon to look to the past to better understand the function of the human knee today.

“For many people, they’re perfectly willing to admit cabbages, skunks, and worms evolved, but they believe humans were created in one fell swoop by God,” says Beard. “In many ways, we can thank our lucky stars that that’s not the case. Imagine if humans were totally distinct from all other life on earth. If we were concerned about curing diseases, our only option would be to perform experiments on other humans. Can you even imagine?”

|

Like Confessing a Murder

Like Confessing a Murder “It was a completely transformative publication in the history of science,” says Beard, “and it transformed biology almost overnight. It was basically a matter of how fast you could read the book.”

“It was a completely transformative publication in the history of science,” says Beard, “and it transformed biology almost overnight. It was basically a matter of how fast you could read the book.”  But the reality is, while nearly everyone links biological evolution to Darwin, his science often gets eclipsed, or lost in translation to the public, because of the controversy that surrounds it. It’s a controversy that scientists say unjustly pits Darwin against God and the literal interpretation of the Bible, stirring a decades-long debate that, according to some, has resulted in a sub-par science education in our country’s schools.

But the reality is, while nearly everyone links biological evolution to Darwin, his science often gets eclipsed, or lost in translation to the public, because of the controversy that surrounds it. It’s a controversy that scientists say unjustly pits Darwin against God and the literal interpretation of the Bible, stirring a decades-long debate that, according to some, has resulted in a sub-par science education in our country’s schools.