Back

A Rare Bird

Turning

his childhood dream of finding dinosaur bones into a grown-up

reality, Carnegie Museum of Natural History paleontologist

Matt Lamanna hopes that the discovery of an ancient flying

creature provides a missing link in the story of bird evolution.

By John Altdorfer

Matt Lamanna is hungry. It’s a few minutes before two

o’clock on an early October afternoon, and he’s

missed lunch because of an unscheduled, last-minute meeting.

Yet instead of catching a bite to eat, the Carnegie Museum

of Natural History assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology

gladly discusses the one appetite he can’t seem to satisfy—his

love for dinosaurs.

“

I was about four years old when I told my parents I wanted

to be a paleontologist,” says the 31-year-old upstate

New York native. “I was a dinosaur fanatic from the start.”

Today, seated in his office at the Museum of Natural History

behind a massive desk and surrounded by crowded bookshelves,

maps, charts, fossil casts and computer equipment, the obsessed

kid who fantasized about finding dinosaur bones is now an

enthusiastic adult changing the way the world looks at the

creatures who

roamed our planet for more than 150 million years. The Proverbial Foot in the Door

At an age when many paleontologists are looking to snag a temporary

university or museum position, Lamanna is pushing the pedal

to the metal on the expressway to success and recognition.

A little more than two years after receiving a doctorate

from the University of Pennsylvania’s department of

earth and environmental science, he owns one of the top jobs

in his profession and a reputation as an important contributor

to the understanding of how dinosaurs and their environments

evolved. Building on earlier work in Argentina and Egypt,

he made a big splash earlier this year as part of a team

that discovered a prehistoric amphibious bird in the mountains

of northwestern China.

A quarter-century earlier, a Chinese

paleontologist found a tiny fossil bird foot approximately

110 million years old at

a site called Changma, about 1,250 miles west of Beijing.

Following the uncovering of this original specimen in 1981,

no further

avian finds from the site surfaced until a former Penn classmate

of Lamanna’s returned to the region in September 2002.

“

Hai-lu You went to Changma because he knew it was an ideal

place to look for more fossil bird specimens,” says

Lamanna. “He

and his team dug there for a few weeks and found the partial

wing of another ancient bird. When he came back to Penn

in March of 2003 and asked me to join him, I was excited.

Even

though my research tends to involve dinosaurs from the

Southern Hemisphere, this kind of discovery was too important

to pass

up.”

Excitement, however, wouldn’t be enough

to drive the project. Even with the approval of the Chinese

government,

the expedition required major funding. As was the case

during a previous dig in Egypt, where he and colleague

Josh Smith

unearthed the bones of one of the largest dinosaurs ever

found, Lamanna turned to the media for a healthy infusion

of cash.

After securing significant financial backing from

the Discovery Channel, Lamanna set out for China.

Collecting An Early Jackpot

Most times, paleontologists don’t expect to uncover a

mother lode of bones. In fact, they anticipate the opposite.

Still, Lamanna never imagined what would greet him when he

arrived in Changma.

|

Paleontologists Hai-You and Matt Lamanna in the Changma

basin.

|

“

There was a crew of eight to 10 Chinese helpers who found the

vast majority of fossils at the site,” says Lamanna. “By

the time we got there, they had already turned up this.”

“

This” is a slender, triangular chunk of brown mudstone

slightly larger than a slice of pie. Embedded in the rocky

sliver are what appear to be a couple of short, slightly gnarly

twigs. They are, of course, fossil bird bones neatly hidden

for millennia between thin layers of shale. At the site, Lamanna

immediately recognized what the workers showed him. The nearly

parallel, slightly raised impressions in the rock indicated

that fossils were just under the surface. To verify his gut

feeling, he and his colleagues sent the specimen to Beijing,

where a technician peeled back shaly layers to reveal a pair

of exquisitely preserved bird legs. At the time, Lamanna felt

he had hit the jackpot, not realizing even bigger payoffs were

yet to come.

“

At best, we were expecting to find a couple of birds, based

on the history of the site,” he says. “When we

got to Changma, and saw that the team had already found a bird,

I figured we had paid the bills. But it just kept getting better.”

If It Looks Like A Duck

As the field season wore on, workers on the site uncovered

fossils by the score. By the end of 2004, the expedition

had produced more than 40 fossil bird specimens, many of

them nearly complete and amazingly well preserved. Over the

next year, the count soared to almost 100. While the numbers

exceeded any imaginable expectations, the bones connected

to tell a compelling story on many levels, as well as providing

additional evidence to support the theory that modern-day

birds evolved from dinosaurs.

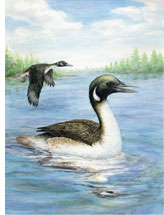

|

Reconstruction of the Early Cretaceous amphibious

bird Gansus yumenensis.

illustration: Mark a. Klinger/CMNH |

To begin with, the fossils

represent a species—Gansus

yumenensis—that wasn’t quite a traditional dinosaur

and not exactly a direct ancestor of today’s birds

either. Dating to the early part of the Cretaceous Period,

these feathered

creatures might resemble at first glance any number of ducks

swimming in the rivers and lakes around Pittsburgh. Some

specimens even preserve remnants of webbing between the toes,

indicating

that the birds could propel themselves and dive in water,

just like a duck. A closer look, however, reveals that Gansus is

no common mallard.

For instance, it is small, maybe no more

than a foot across from wing to wing. Further inspection

of those little bones

shows structures long missing from current birds — a

pair of claws on each wing. The skeletal structure also

provides evidence that it was a good flyer, but not as

adept as modern

birds. As Lamanna points out, Gansus is Model-T

compared to its living relatives. Still, this primitive

bird is yielding

an abundance of information, thanks to near-perfect environmental

surroundings that helped preserve its fossils through the

ages.

“

The conditions in the area are special,” says Lamanna. “When

the birds died, they sank to the bottom of an ancient lake.

Along with weaker currents than you’d find in a river,

the lake may have not had much oxygen at its bottom, which

means there weren’t scavengers down there to eat

the birds. Over time, sediment covered them and preserved

them

in the condition we found them.”

After Gansus died

out, eons passed. The lake dried up. More rocks were

laid down, further protecting the fossils.

Then,

beginning about 70 million years ago, the Indian sub-continent

smashed into southern Asia, causing a violent, relentless

grinding collision that thrust once low-laying lands

upwards to form

the Himalaya Mountains and the Tibetan Plateau. Over

time, the parched lakebed eroded, and its fossils were

driven

closer to the surface. Today, the barren, brownish landscape

bears

little resemblance to the once lush wetlands, which makes

fossil hunting an easier task. With finds becoming nearly

commonplace,

the surplus of specimens will allow Lamanna and others

to probe more deeply into Gansus and the world it inhabited.

A nearly complete fossil skeleton

of Gansus yumenensis shown at actual size. Feathers are

preserved adjacent to

the wing at left. Photo: hai-lu you/cags

A Lost World Revisited

Sometimes, a window on the past is as easy to open as turning

the pages of a history book. Understanding the life and times

of dinosaurs, however, proves more difficult. The reality

is that solving the puzzle of how these prehistoric flyers

lived is a matter of studying what remains long after their

deaths.

“

Fossils are the only direct evidence of large-scale evolutionary

processes,” says Lamanna. “That story can’t

be told in detail without additional discoveries and new

studies of existing specimens. Because we have so many Gansus specimens,

we already know a lot about it. And the additional specimens

will allow us to determine further aspects of Gansus’ biology,

such as how males and females might have differed, how their

populations were structured, how fast they grew to adulthood.

All this is unknown now. But with so many Gansus bones available,

we can start slicing into them to find what answers may be

inside.”

Along with Gansus and other extinct birds,

the expedition yielded beautifully preserved fossils of

plants, fishes,

turtles, a

salamander, and even insects with traces of their original

color patterns. These finds will help paleontologists accurately

recreate the world Gansus lived in—a skill at which

Lamanna excels.

“

Matt is gifted in the sense that he’s able to contextualize

fossils,” says Chris Beard, Carnegie Museum of Natural

History curator of vertebrate paleontology and section

head. “You

can train almost anyone to learn how to find fossils. But

beyond that skill is the ability to address questions in

new ways.

Matt has the ability to put a single fossilized specimen

in the big picture and offer new insight on how dinosaurs

evolved

and how life on Earth changed through time.”

That

talent also will help Lamanna in his role as lead scientific

advisor on Dinosaurs in Their World, the Museum

of Natural

History’s stunning exhibit that will nearly triple

the size of the former Dinosaur Hall. When unveiled late

next fall,

Dinosaurs in Their World will range over 25,552 square

feet, enough space to display over 15 mounted dinosaur

skeletons

and more than 200 other ancient plants and animals in a

way that captures them in their habitat as never before.

“

Visitors are going to see newly restored, much more dynamic

and scientifically accurate dinosaurs,” says Lamanna. “We’re

sweating the details. Not only are we grouping our dinosaurs

into their proper time periods, we’re recreating the

ecosystems they inhabited, too. When visitors walk through

the exhibition, they’re going to feel as though they’re

actually walking through the same environments the dinosaurs

lived in. The only thing missing will be the meat on their

bones.”

The Best is Yet to Come

As of May 2006, the number of identified dinosaurs stood at

527. That total represents a mere drop in the paleontological

bucket, says Peter Dodson, professor of anatomy at the University

of Pennsylvania’s school of veterinary medicine.

“

At the current rate of discovery of about 15 dinosaurs a

year, the number of dinosaurs that will be found in the

next 30 to

50 years should reach about 1,275,” says Dodson, who

instructed Lamanna at Penn.

To discover those dinosaurs in

waiting will require imagination and innovation, two words

that describe Lamanna.

“

No one works harder than Matt,” Dodson says. “He’s

followed his childhood dream to find fossils that will

grab people’s attention. His work so far is off the

charts.”

With Lamanna on board, the Museum of Natural

History stands poised to reinforce its reputation as one

of the world’s

leading contributors to dinosaur research and discoveries.

“

Matt is a perfect example of the type of scientist we want,” says

Beard. “He not only puts us on television when The Science

Channel makes a documentary, but he also helps to

advance our public programs, lectures and exhibitions.

I expect great things

from him far into the future.”

With Gansus and

Dinosaurs in Their World already near the top of a crowded

resume, Lamanna admits that the hunger

that led

him to the Museum of Natural History remains strong.

“I’d like to get more scientific publications out there,” he

says. “I’d like to establish a domestic field program to build the

museum’s collections from the Cretaceous and other periods of the Age of

Dinosaurs. And I already have a backlog of unstudied fossils that’ll last

me at least the next 10 years. So I’ve got my work cut out for me. But

this is my dream job.”

Back | Top |