Back

Disassembly

Required

Piece by piece,

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s most famous residents are

being prepared for a new home—a process that’s

taking a team of artists back to the Mesozoic Era by way

of New Jersey.

By Christopher Pratt

It’s a familiar story: after going nowhere for ages,

she’s finally discovered, given a quick makeover and

a catchy name, and thrust in front of the public where she

becomes an instant hit, entertaining big crowds day and night.

Then one day, when she’s maybe a little long in the tooth,

a bit creaky in the joints, the same people who built her up

tear her apart and ship her off to somewhere in New Jersey.

Which, of course, merely sets the stage for her dramatic comeback

on a stage that’s bigger and better than ever. Happy

ending.

That’s sort of what’s playing out these

days at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, where Apatosaurus

louisae and her peers are experiencing the most extreme of makeovers.

Their skeletal bodies are being painstakingly disassembled

and then shipped out—ever so carefully—to be

cleaned and preserved before becoming the main attraction

of Dinosaurs in Their World, the museum’s new dinosaur exhibits

that are scheduled to open by 2008 in a space three times

the size

of the former Dinosaur Hall.

Driven by more than 100 years

of scientific learning, the exhibits will take visitors

on

a chronological journey through distinct periods of the

165 million-year reign of the dinosaur: the Late Triassic,

Late

Jurassic (the exhibit’s highlight, displayed in a new

atrium), and the Early and Late Cretaceous periods. Not

only will visitors see specimens depicted in their specific

time

periods, amid plants and other animals that shared their

ecosystem, but they’ll also see dinosaurs positioned in more dramatic

and scientifically accurate poses.

“

This is one of the largest dinosaur exhibit renovations

ever undertaken,” says Matt Lamanna, the museum’s

new assistant curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and

its chief

dinosaur researcher. “Scientific understanding of

dinosaurs has advanced immeasurably since Diplodocus

carnegii first went

on display in 1907. Dinosaurs in Their World will

reflect that enormous body of research.”

It’s

a once-in-a-century job that requires only the best in

the obscure and hard to

pronounce business of dinosaur “disarticulation.” And

the best is Phil Fraley Productions of Hoboken, New Jersey. “Incredibly

Heavy, Fragile, Weak Objects”

Since March of 2005, in a fascinatingly tedious three-step

process, Phil Fraley and his team have taken apart,

bone by bone, five of the museum’s 15 dinosaur

skeletons for refurbishing and eventual re-mounting

in their new home. The “disarticulation,” or

disassembly, of Diplodocus carnegii (discovered in

1899), Apatosaurus louisae (found in 1909 and named

for Andrew Carnegie's wife), Allosaurus, Protoceratops,

and Tyrannosaurus rex was just completed in August.

Three more specimens—Dryosaurus, Camptosaurus,

and Corythosaurus—could also be freed from their

two-dimensional wall displays for mounting as 3-D,

freestanding skeletons.

Phil Fraley has spent 25 years

learning all about dinosaurs—mostly

how to dismantle, restore, and rebuild their skeletons.

For the past seven months, Fraley and his team of ironworkers,

welders, machinists, and riggers have been carefully,

meticulously freeing the Carnegie dinosaurs from the

iron supports that have held them together and propped

them up for the better part of a century.

All told, Fraley’s

methodical disassembly line has removed more than 1,000

ancient femurs, fibulas,

tibias, ribs, pelvises, and jawbones, and then numbered,

photographed, cataloged, and packed them in foam-padded,

custom-made crates for shipping to Fraley’s

New Jersey studio. Using everything from a huge hydraulic

crane down to precise hand tools, they took apart skeletons

whose pieces weighed as much as a ton. And which, although

they may look pretty solid, are, according to Fraley, “incredibly

heavy, fragile, weak objects. All the glue joints that

were put in to replace missing parts are wearing out

and need to be replaced.”

Truckload by valuable

truckload, all the parts that aren’t

missing have been making the journey to Fraley’s

11,000 square-foot, hangar-like studio a few miles outside

of Manhattan. There, a team of 15 restoration artists

and sculptors has begun the painstaking task

of repairing and restoring the artifacts so they will

last another 100 years.

Over the next two years, they’ll

dig out the epoxies, glues, fillers, patches, and other

gunk applied over

the past century and then repair, rebuild, re-seal, and

re-pack them for shipment back to Pittsburgh. Every step

of the restoration is being documented for the benefit

of the next team of disarticulation specialists, restoration

artists, or whatever they’ll call themselves in

the 22nd century.

The project is a true collaboration

between Fraley’s

crew and the museum’s curators and exhibits staff,

all of whom had a hand in choosing the dinosaurs’ new

poses. “Phil is a great guy,” says Lamanna,

who admits to having been a bit intimidated upon first

meeting him. “We see him as a colleague and a friend.

He really knows his stuff, and he’s added value

from the beginning. He’s so good at what he does,

it leaves me free to concentrate on what I do.”

Phil Fraley and his crew have

dismantled, bone-by-bone, five of the museum’s 15 dinosaur skeletons; carefully

packed each bone; then shipped the precious cargo to Fraley’s

studios in Hoboken, New Jersey, for refurbishing and eventual

re-mounting.

Handling With Care

Fraley looks more like the pro football player he once

aspired to be than the quasi-scientist he’s become.

And he’s apt to use the language of carpentry,

a skill he learned from his father, when expressing

the importance of his work. “

Similar to how an old house settles on its foundation,

to all eyes a specimen looks sturdy and strong,” he

explains. “But then you start digging around and

you begin to see that as the specimen has settled, the

vertical supports have twisted, literally two inches

off center in opposite directions.”

While disarticulating

a shoulder blade, for instance, Fraley’s team found

it was held together by just two threads, literally. “A

good jolt by some guy in there with a waxing machine,

who inadvertently bumps

the base, and….” Fraley knows he doesn’t

have to complete the sentence to make his point.

The same

care will have to be taken during the rebuilding phase

when, Fraley assures, the team will be very aware

that they’re “working with specimens that

are 160 million years of age. They’re big, they’re

heavy, they’re fragile, and even if they’re

handled correctly, they can break. And then you have

to stop everything and put it all back together again.”

Fraley

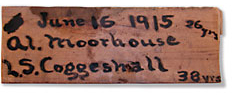

and his crew did stop everything when they stumbled upon

a message from the past. While dismantling the Apatosaurus skeleton,

they found a wood plank with the names and ages of the

two men who erected it in 1915: L. S. Coggeshall,

the 38-year-old brother of Arthur Coggeshall, the museum’s

famous then-fossil preparator; and 26-year-old Al Moorhouse.

Months earlier, the museum’s preparation staff

came upon another message from the past inside the wall-mounted Camptosaurus (still

in its stone matrix). The note, rolled up inside a small

jar, gave some vital specs: the year

of discovery, 1928; the names of the men who prepared

and mounted it, which again included L. S. Coggeshall;

and the year it had been taken down and lighted, 1934.

Matt Lamanna finds these discoveries to be a “cool

connection between the past and present.” Fraley

and his crew did stop everything when they stumbled upon

a message from the past. While dismantling the Apatosaurus skeleton,

they found a wood plank with the names and ages of the

two men who erected it in 1915: L. S. Coggeshall,

the 38-year-old brother of Arthur Coggeshall, the museum’s

famous then-fossil preparator; and 26-year-old Al Moorhouse.

Months earlier, the museum’s preparation staff

came upon another message from the past inside the wall-mounted Camptosaurus (still

in its stone matrix). The note, rolled up inside a small

jar, gave some vital specs: the year

of discovery, 1928; the names of the men who prepared

and mounted it, which again included L. S. Coggeshall;

and the year it had been taken down and lighted, 1934.

Matt Lamanna finds these discoveries to be a “cool

connection between the past and present.”

Phil Fraley

regularly makes his own connections with the past. “I

think the animal, in a lot of ways, guides us,” he

says. “Someone asked a sculptor

once, ‘How do you know what you’re going

to carve?’ And he answered, ‘Because it’s

already inside. I’m just the instrument that allows

it to come out.’”

He may make his living

restoring the past, but Phil Fraley isn’t inclined

to look even as far back as his last project. “The

satisfaction that I derive from doing this is the process.

It’s the getting there.

And when you finally get there, there’s no point

in standing around looking at what you did.”

Fraley

does allow himself to reflect on those he’s

met along the way. People like Carnegie Museum of Natural

History’s Mary Dawson, curator emeritus, who remains

an important fixture in the museum and the world scientific

community after retiring from her three decades on the

museum’s staff: “She’s a tremendous

person, a great scientist…I respect her so much

for all she’s been able to do and the obstacles

she’s overcome so early on as a woman in this field…” Fraley

says, adding, “the entire Vertebrate Paleontology

staff here really and truly is exceptional.

“

What continues to make my work exciting to me,” he

says, “are the people. The artists, the curators,

the scientists, the museum administrators, the architects,

all these people with all these wonderful ideas and sense

of purpose…moving forward and creating something

greater than all of them as individuals, that collectively

is worth something.

“

It’s not just for us, it’s for people who

come after us,” he says of their handiwork. “For

the next hundred years, every school kid that lives in

Pittsburgh will be coming here and looking at this, and

maybe it’ll inspire one of them, maybe it’ll

say ‘look, anything is possible.’ To me,

that’s what it’s all about.”

Well-articulated.

Back | Top |