|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Dan Leers, Carnegie Museum of Art’s new curator of photography, draws on the collections of all four Carnegie Museums to explore the power of multiple photographs. From daguerreotype to Polaroid to iPhone and Instagram, photography has long been at the center of visual culture. When British photographer Eadweard Muybridge rigged a set of tripwire cameras to capture his famous Victorian-era images of humans and horses in motion, the results proved that series of photographs could illustrate fast movement and the passage of time. Many artists would adopt the series as a way to portray quirks of culture, place, and persona, grouping their work into sequences that express more than mere moments. Strength in Numbers: Photography in Groups, on view through February 6, 2017, at Carnegie Museum of Art, trains a wide-angle lens on many rarely seen groups of photographs in the Museum of Art’s collection. It also highlights a few unearthed treasures from the collections of sister museums Carnegie Museum of Natural History, The Andy Warhol Museum, and Carnegie Science Center. Exploring the four archives with a fresh eye, photography curator Dan Leers juxtaposes series of work that span the globe and were created as early as 1887 and as recently as 2011. Nearly 100 images by 25 photographers jump across multiple eras and continents, linked by their focus on three themes: people, place, and perspective. “More than 80 percent of the works in this show are on display for the very first time,” says Leers, who joined the Museum of Art staff last April. “That’s a conscious decision. Our photography department is relatively new. It’s a medium not widely associated with the museum outside of ‘Teenie’ [Harris]. This exhibition helps show off what we have and highlights some excellent works.” Before returning to Pittsburgh, the Shadyside Academy graduate was a New York-based independent curator. He worked on the 2013 Venice Biennale, serving as an advisor on contemporary African Art, and as a curatorial fellow at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. This expertise drew Leers to share the work of two artists in particular in Strength in Numbers, culled from some 5,000 images in the museum’s collection: mid-century Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, who in 2007 became the first photographer and the first African artist to receive a lifetime achievement award at the Venice Biennale, and Frenchman Eugène Atget, whose archives were a formative acquisition for MoMA.

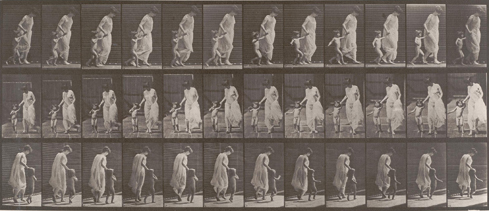

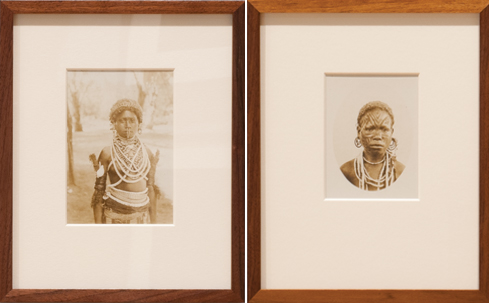

The oldest works in the show focus on people. They were created using the early photographic processes of albumen and collotype printing, highlighting passing technologies as well as time. Muybridge’s inventive technique is represented by two tender 1887 sequences, one of a mother and small child walking together, the other of a mother and child embracing. On the same wall, Leers displays five images marking coming-of-age and bridal rituals of Wanigela tribeswomen in a tiny Papua New Guinea village. These small albumen prints, made in 1905 by Australian missionary Percy John Money, are part of the anthropology collection of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Hung in between these historic images is a set of four full-length portraits of children from Pine Flat, California, created a century later by Sharon Lockhart. In a nod to the 19th-century American tradition of the portrait photographer, Lockhart, who contributed to the 2008 Carnegie International, Life on Mars, set up a studio in the center of rural Pine Flat, using only a black cloth backdrop and natural light, and invited the children to have their portraits taken. “Lockhart’s work bridges Muybridge and Money,” says Leers. “Kids grow up fast—that’s not a new idea of course—but photos in groups can illustrate that nicely. This wall of images traces an arc of maturity. In Muybridge, we have the enduring mother and child connection. In Lockhart’s portraits, the children are mirroring more mature behavior and positions. It culminates in the Money series, showing us that even at age 13, in certain cultures, there was sexual and marital maturity.”

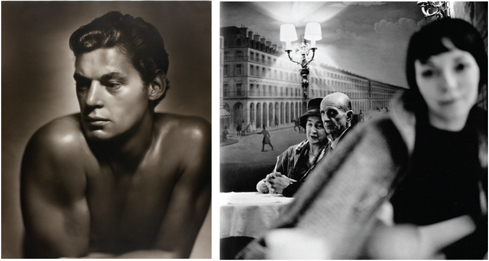

Taking portraits allows a photographer— and the photographer’s audience—to get a glimpse inside someone else’s world. Visitors to the 2013 Carnegie International will recognize Zanele Muholi’s visual record of black, marginalized LGBTQ community members from her home country of South Africa. These striking black-and-white portraits hang not far from a selection of images from German photographer August Sander’s five-decade-long project, People of the Twentieth Century, a collective portrait of German society that has fascinated viewers since its debut in 1927. The images are compelling, in part, because Sander photographed hundreds of German citizens and categorized them by type—social class and occupation—rather than as individuals. Celebrity personas, a central theme of Andy Warhol’s work, are also included in this section of the exhibition, with Warhol’s Polaroid self-portraits and the gorgeous silver gelatin prints of George Hurrell, an MGM photographer who created the silent era’s most iconic images of Hollywood movie stars. Hurrell, says Leers, was the master of Hollywood glamour, sculpting his subject’s faces with brilliantly orchestrated light and shadow.

Power of PlaceSerial photography can powerfully document change in landscape. Charles “Teenie” Harris, perhaps the city’s best-known photojournalist, captured Pittsburgh faces and places for decades. Leers acknowledges Harris’ commitment to place with six images—one of the demolition of Hill District landmark Crawford Grill No. 1, and the others featuring the rise of the Civic Arena, which changed Harris’ native Hill District forever. These black-and-white scenes from the late 1950s and early 1960s are displayed not far from a nine-image sequence, in color, by British photographer Paul Graham, who in 2004 made Pittsburgh his initial stop on the first of many cross-country road trips. Described by Leers as a “small focused vignette,” Pittsburgh (man cutting grass), taken from the series shimmer of possibility, captures a sense of movement and passage of time—emblematic, in this case, of the back-and-forth motion of manicuring an expansive lawn as dusk approaches.

Creating a natural history, American Robert Flick spent years celebrating the rebirth of a California canyon by a devastating forest fire. At Solstice, 118A, a 72-image grid, graphs the minute details of a landscape morphing from destruction to regeneration. By contrast, the work of Eugène Atget, a French surrealist and pioneer of documentary photography, comprises an elaborate elegy for the past. Atget faithfully chronicled Paris’ fin de siècle or end of the century transition from storefronts and street stalls to post-war modernity, creating a record similar to Harris’ depiction of Pittsburgh history. “He sold his pictures commercially to painters to use as models,” notes Leers. “If someone came in and said, ‘I need to paint a spiral staircase,’ he’d say, ‘go to aisle two.’” But as Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s designs transformed the city, Atget chose an outdated technology, a wooden bellows camera, to memorialize its serene past. “He had a personal need to halt the passage of time around him—it was inevitable, but if he took tens of thousands of photos, he could freeze time, if only in his mind,” says Leers. “Placing it right smack in the middle of the show allows visitors to see a very real evolution in photography, from still imagery to motion picture and film,” Leers says. But six months ago, she had an epiphany. “When I walk around my neighborhood, just a 20-minute walk, I always take my phone with me,” says Fiskin. “Suddenly I realized—there’s a camera in that! I took 1,000 images in three days.” But she doesn’t want to merely contribute to the “massive tidal wave” of images online. So she’s embarked on a film project with some 6,000 digital images.“The film will grapple with how do you sort them?” she explains. “The fun is in the ideas and the editing.” In the show’s final section, Leers considers the role that both the photographer and the viewer play in making an image. Here he includes a series of images by Malick Sidibé. As a hip young commercial photographer, Sidibé documented the late 1960’s nightlife of his native Bamako, Mali, in flash photography. “He’d race home, develop the images, and put the prints in his studio window the next day,” explains Leers. “He knew the trends, and he had access”—in this case, to a generation celebrating its nation’s newfound independence. Also highlighted is newly acquired work by Braddock’s own LaToya Ruby Frazier, who was honored with a MacArthur Fellowship in 2015. In a trio of black-and-white photographs made in her hometown, Frazier shares tender, intimate moments between her and her family. By inviting viewers behind her camera and into her personal life, the artist gives access to intimate moments normally off-limits to outsiders. Access is also important to the work of Newsha Tavakolian, whose series Hajj, Trip of a Lifetime follows the Iranian artist as she goes on a pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, allowing viewers to experience one of the most important journeys in Islam through the eyes of a practicing Muslim.

Amateur photographers also make their way into the show: the crew and family members of the USS Requin. Now docked on Pittsburgh’s riverfront, Carnegie Science Center’s submarine once patrolled the Eastern Seaboard and Mediterranean after World War II. Images of the Requin’s John Dobranski and his crewmates on deck and in foreign ports, displayed together like family snapshots, suggest that military missions can be as memorable as religious ones. “A group of photographs can do things that a single image can’t,” argues Leers. “[Henri] Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’ is possible. But frequently, other moments around that moment give context and more accurately mirror our world. We don’t move in single moments—every image flows into the stream of the contemporary.”

|

|||||||||||||||||

Head-to-toe Science · Art as an Equalizer · Earth in the Age of Humans · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Jeffrey Inscho · Science & Nature: Lion Attacking a Dromedary · Artistic License: New Voices of Appalachia · About Town: Reconstructing Pittsburgh's Atomic Past · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |