|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lost Kingdoms Found

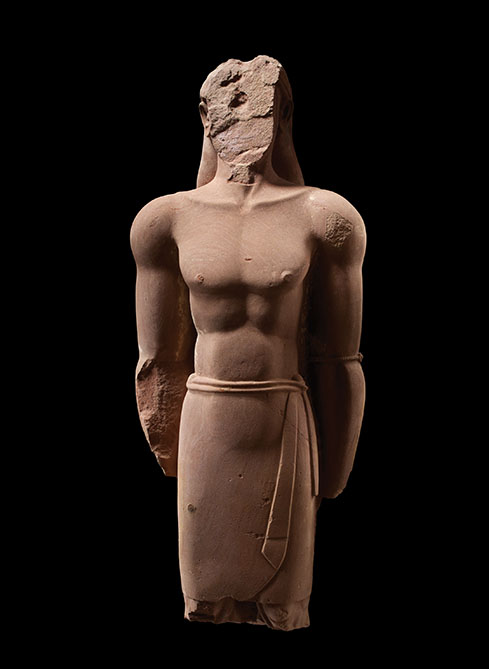

Through precious artifacts from the Saudi Kingdom’s storied past, a new exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Natural History reveals the roads that led to, and created, Arabia.Not far from the entrance to the R.P. Simmons Family Gallery in the Museum of Natural History stand three chiseled, seven-foot superheroes with muscled chests, mighty biceps, and clenched fists. The handsome figures, inspired by Egyptian or Syrian art, embody the pride of a powerful ancient empire that coexisted with ancient Greece, yet was literally lost to the sands of time.

“For too many people, Arabia may be a cliché—oil, camels, and sand dunes,” says Cynthia Culbertson, an Arabist and scholar who has lived and studied in the country for decades. “Yet it was a crossroads of humanity for thousands and thousands of years.” The exhibition’s sandstone sculptures, each weighing more than a ton, are believed to be images of kings from the Lihyan dynasty that flourished in northern Arabia from the 6th-3rd century BCE on. The Lihyanites were among dozens of cultures that shaped the peninsula’s history, building fabulous wealth a thousand years before the rise of Islam. More than 300 relics, ranging from simple anthropomorphic grave markers to a child’s sumptuous gold death mask, illuminate the complex interactions along the famed “Incense Road,” later followed by international pilgrims to Mecca. The impact of that worldwide hajj is also illustrated in the exhibition, which opens June 22 and will run through November 3.

“There’s statuary, gold, metalwork, and jewelry. Most people will never get to visit these sites, but in this show they can see the richness of the civilizations.” - Cynthia Culbertson, Arabist and ScholarHistory revealedCarnegie Museum scientists have provided a compelling prequel to the exhibition through research on the ancient rock art of the Arabian Peninsula, also on display through the fall (see sidebar at the end of this story). Frequent references to Arabian settlements and kings are found in the Bible and Roman history. But further evidence and artifacts have come to light far more recently. Some of the most spectacular finds—like that priceless funeral mask—have been discovered in the past 20 years. The evidence suggests the Arabian Peninsula was a bridge between Africa, Asia, and the Mediterranean as early as hundreds of thousands of years ago. Sandra Olsen, a zooarchaeologist and director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Center for World Cultures, recently found that evidence at her feet.

“During a conference in Saudi Arabia in March, our hosts took us to a tiny island in the Red Sea, north of Jeddah,” she recalls. “It’s thought to be where boats cross- ing from Egypt had to stop and pay a tax before they could enter the nearby Arabian port. There were still pot shards and glass just lying in the sand. One Saudi archae- ologist reached down and picked up a gold coin. It was from the Aksum Kingdom of Ethiopia [400 BCE-1000 CE]—and beautifully preserved! We were all excited by the find. It was clear there was a large settlement there.” Olsen says she’s thrilled that Pittsburgh was chosen as the second stop on the exhibition’s American tour, sponsored by Saudi Aramco and Exxon Mobil. Having debuted at the Louvre in 2010, the exhibition opened to glowing national reviews at the Smithsonian Institution’s Sackler and Freer Galleries in 2012.

The Carnegie Museum curator, whose expertise in ancient horse cultures first drew her to Arabia five years ago, predicts the tour’s impact on American audiences will be as profound as that of the first Chinese archaeology exhibits to visit the United States in the 1970s, or the blockbuster Tutankhamun or Pompeii exhibits that followed. “It’s at that level,” says Olsen. “The Saudis are allowing their most precious artifacts to travel. It’s a great, great honor. I’ve been at the museum 23 years. In that time we’ve had some beautiful exhibitions, but we’ve not had one this spectacular. It’s wonderful because it helps people understand the history of Arabia in a way that’s not covered in our educational system.” Fellow scholar Culbertson believes the depth of the exhi- bition makes it especially impressive. “It’s not one genre, or one standout item. There’s statuary, gold, metalwork, and jewelry” drawn from remote sites all over the country, she says. “Most people will never get to visit these sites, but in this show they can see the richness of the civilizations.” Incense crossroads to cosmopolitan citiesWesterners recall frankincense as one of the three gifts of the Magi, carried from the East to be presented to the infant Jesus. It was an especially strategic Arabian asset. “Frankincense was the oil of its day—so precious,” says Culbertson.

Captured from tree sap, the aromatic was used in embalming, perfumes, and worship. The Roman historian Pliny reported that Emperor Nero burned an entire year’s production of incense from Arabia at the funeral of his wife, Poppaea, in 65 CE; ornate incense burners in the exhibit are several hundred years older. Traded by camel caravan and ship, Arabian incense made its way to Greece, India, and China.

The sandstone giants of the Kingdom of Lihyan, for example, came from its capital of Dedan, in the valley of Al Ula, founded in the 6th century BCE. The kings shrewdly capitalized on their crossroads location, taxing passing camel caravans, supplying fresh produce, and constructing temples to their gods inscribed in the Lihyanite language. Olsen, who recently visited Dedan, says it reminds her of Arizona’s Sedona region. “It’s a green valley with an oasis. You can see why there was settlement there,” she recalls. “And those monumental statues—they just take your breath away.” As the empires of Greece and Rome expanded, Arabian fashions reflected their influence. Artifacts found at Qaryat al Faw, a site in southern Arabia (4th BCE-5th CE), vividly portray the lifestyles of its rich and famous, from their chic hairstyles to jewelry and furniture. The so-called “City of Paradise” was home to many tribes, who lived in luxurious multi-story stone houses decorat- ed with ornate carvings, glass, and frescoes. “We don't think of Arabia and frescoes, but this was a cosmopolitan place,” notes Culbertson. One fragment of a wall painting depicts a handsome man with glossy dark curls and a fashionably thin mustache being offered grapes by smaller figures, probably his servants. The Greco-Roman style is echoed in a bronze funeral bed, elements of which shine in the exhibition. The gilt bed head is adorned with busts of the goddess Artemis and the elegant head of a horse, draped in a panther hide. The horse, still beloved in Saudi culture, flanks the Greek goddess, illustrating the fusion of cultures.

“We’ve had some beautiful exhibitions, but we’ve not had one this spectacular. It’s wonderful because it helps people understand the history of Arabia in a way that’s not covered in our educational system.” - Sandra Olsen, Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History's Center for World Cultures

The child, thought to be about 6, was the honored daughter of a wealthy family. She was buried with rubies, pearls, turquoise, the mask, and even a golden glove, surrounded by imagery of Greek gods. The Tomb of Thaj, along with other finds in the region, have led researchers to identify the area as the likely location of the fabled city of Gerrha, the City of White Walls. “It’s hard to find a time when Arabia was not interacting with other cultures,” notes Olsen. “Although there was a lull between the decline of the incense trade [around 300 CE] and the rise of Islam, they were always exchanging products with their neighbors.” The Road to MeccaThe Islamic calendar begins in 622 CE, when the Prophet Muhammad made what has been called “the most momentous journey in the history of Arabia.” With his followers, he left Mecca, the city of his birth, for Medina. When he died a decade later, he had unified the Arabian Peninsula in one faith and culture. Thus began a rapid series of international conquests and conversions.

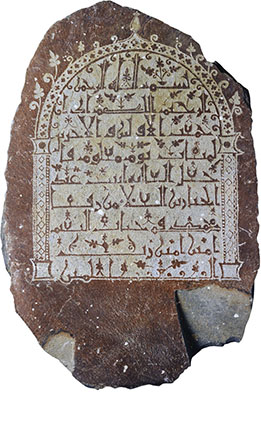

The pilgrims followed, particularly in present-day Yemen, and their journey closely tracked the earlier Incense Road. Other pathways—from the coastal city of Jeddah west across the Red Sea, overland east to the cities of Basra and current-day Bahrain—were professionally built and organized into an efficient network. Mosques, with sophisticated architectural advances, arose along the way. “People forget that ancient cultures had to develop the engineering to configure square buildings that supported round domes,” says Olsen. “The Arabs took information from the Greeks and Romans and carried it further. They excelled in architecture, weaponry, mathematics, physics, and astronomy—and they sailed as far as Southeast Asia by the 11th century. Even today, madrasas (Islamic schools) excel in the physical sciences.” Islam also focused on a single written language, Arabic, to spread the word of the Koran. With the Islamic prohibition on depicting the human form, Arabic script also became an exuberant artistic element, adorning public spaces. The massive 17th century door of the Ka’ba in Roads of Arabia shows the genre literally at its height. The 11-foot door panels, iced in gilded silver leaf on a wooden base, are etched with Koranic verses, leaves and flowers. The gift of the Ottoman Emperor Sulayman the Magnificent, they are as sophisticated and elegant as the Thaj tomb ornaments or the Lihyanite statues, embodying a civilization discovered by Babylonians, Greeks, Romans—and now, Pittsburgh. Roads of Arabia is organized by the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with the Saudi Commission for Tourism and Antiquities of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. ExxonMobil and Saudi Aramco are principal co-sponsors of the tour of Roads of Arabia in the United States. Sponsorship is also provided by The Olayan Group, Fluor Corporation, and Layan Cultural Foundation.Carnegie Research in the Desert

The Carnegie Museum connection to the Roads of Arabia stems from fieldwork by Sandra Olsen, zooarchaeologist and director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Center for World Cultures. While conducting research for a major American exhibition on the Arabian horse, one of the world’s most storied animals, she visited examples of prehistoric rock art throughout Saudi Arabia. Olsen immediately realized that panoramic Gigapan photography, a technology developed by computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon University and NASA, could digitally document the remote sites. Intrigued, Saudi Arabia’s Layan Cultural Foundation invited Olsen and Chris Beard, the museum’s Mary R. Dawson Chair of Vertebrate Paleontology and Olsen’s husband, to oversee the project with expert Majid Khan and photographer Richard T. Bryant. During two field seasons, in 2010 and 2011, the pair journeyed into harsh Saudi deserts, often working at night, to conduct their research. Petroglyphs are still being discovered through- out Saudi Arabia, and Olsen, also an expert in extrapolating cultural data from skeletal remains, is fascinated by what they reveal. “In rock art, people are documenting their lifestyles,” she says. “You learn from the art what you can’t learn from the bones.” One of the earliest petroglyphs discovered is a carved 6,000-year-old human handprint, found on a sandstone boulder at Shuwaymis, a study site in northern Saudi Arabia. Other carvings depict bulls, camels, dogs, and wild game, as well as groups of figures dancing or fighting, and early writings. In addition to Gigapan, the team also used polynomial texture mapping and laser scanning, which allow three-dimensional views of the rock surface. Visitors will be able to zoom in on examples of the work at a computer kiosk near the Roads of Arabia exhibition. The research is also documented online at www.saudi-archaeology.com. “A few moments in my career have been very moving,” Olsen reflects. “One was being in the desert at night in January.” As Bryant and Beard completed some photographic work, Olsen found herself alone with the team’s Saudi guides, sipping cardamom-scented coffee and warming herself by a campfire under the stars. “We were always treated very, very well,” she says of the experience. “In the desert, you learn that life depends on hospitality.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Past Meets Present · Family Matters · Celebrating a Great Ride · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Chairman's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nick Bubash · Artistic License: Pop Cabaret · Field Trip: “Shocking Success” in Libya · Science & Nature: Building for Bees · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |