Summer 2013

Summer 2013|

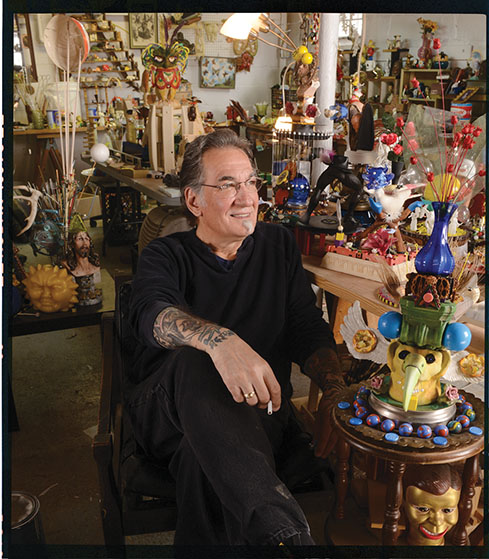

Nick Bubash

Part vulture, part shark, the figure could be a little-known mythological beast. The Vark, however, is a found-object sculpture by artist Nick Bubash—his tongue-in-cheek proposal to replace the bald eagle as America’s national bird. A Pittsburgh native, Bubash moved to New York City in the late 1960s, where he learned the art of tattooing from his future mentor, influential underground artist Thom DeVita. “He brought everything into his art,” says Bubash. “If you see his studio, it’s a mishmash of things from all cultures; things he’s picked up off the street.” That sounds a lot like Bubash’s studio at Route 60 Tattoo, a shop he opened in 2008 in McKees Rocks (his original 1975 shop was one of only several hundred in the country at the time). His basement workshop is overflowing with “little vignettes,” as he calls them, sculptures like The Vark that present sardonic humor and ferocious imagery through a dizzying range of materials and objects, from plastic toys to religious statues. “Most of the stuff is just plain fun,” says Bubash. Formally trained, his work has been collected and shown by galleries and museums across the United States. His latest exhibition, Nick Bubash: The Patron Saint of White Guys That Went Tribal and Other Works, opens June 15 at The Andy Warhol Museum, and features 30 mixed-media sculptures. The inspiration for the show’s title is a 3-foot clay statue of a naked man that Bubash covered in tribal designs and enshrined in a lattice of spent tattoo needles. So, “white guys that went tribal”—why do they need a patron saint?They’ve certainly afforded me a living over all these years, so I’m grateful to them, maybe that played into giving them a patron saint. It just all came together. The sculpture, I did that many, many years ago. Later, I painted it tribally, and in 1993 it traveled all over the country in a show called Eye Tattooed America that Ed Hardy put together. So I’ve had that sculpture for quite a while, and it’s found its way into something else now. Your sculptures combine or tweak religious imagery. Does religion inform your work?I think I’m a spiritual person, but not a religious person. I was raised a strict Catholic, so all those images were hammered into me. I don’t believe in this kind of thing, but I still hang on to the images. And I use them freely; I take license. But I don’t make fun of things—I have fun with things. Your work has caught the attention of museums, but also a celebrity or two?My work is in multiple museum collections, including the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, but it’s also part of the personal collections of Lou Reed and Penn and Teller. Your mother was an artist. Did she encourage your formal training?I learned to draw at my mother’s knee and to this day I can draw a really good woman’s knee. She told me, “If you can’t draw, you can’t be in the club.” I grew up at Penn State—my dad was a professor there—and I was always at Saturday morning arts classes. Took art all through high school. I was about 31 years old when I decided to get a formal art education, studying figural sculpture and print making at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Then you spent some influential time in India?I received a grant and traveled and studied all over the country. I was interested in the classical Indian bronze sculptures from the Chola and Pallava eras. I’m drawn to ancient imagery—from Indian art and many other cultures. Once you collect all of these objects, how do you decide which ones to bring together in a work of art?A psychologist once told me, if you take a person—any person, up to a poin—and sit them in a room with a bunch of objects in front of them, eventually they will begin to organize the objects. It’s just a natural, human thing to do. I organize them in a way that fits my sense of aesthetics. I surround myself with 10,000 things and they come together on their own. But your works aren’t random collisions.It’s something that I’m focused on, so I’m observing what’s going on, even if it’s just chance. If something falls to the ground and breaks into 10 pieces, I look at one of those pieces and think, “Wait a minute, I know where that goes!”

|

Lost Kingdoms Found · Past Meets Present · Family Matters · Celebrating a Great Ride · Special Section: A Tribute to Our Donors · Chairman's Note · NewsWorthy · Artistic License: Pop Cabaret · Field Trip: “Shocking Success” in Libya · Science & Nature: Building for Bees · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |