|

|||||||||||||||||

Japanese, Long Procession of Toads, Meiji Period (1868–1912), Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Section of Anthropology |

The Carving out of a Collection

The art and natural history museums unite to reveal a collection of rarely seen Japanese woodblock prints and ivories built in large part due to a passion shared by two divergent personalities.

Heinz, a museum patron and influential collector of Japanese art and artifacts, is at the center of the new exhibition, “Japan is the Key…”: Collecting Prints and Ivories, 1900–1920, an inventive pairing of highlights from the museums’ significant collection of iconic Japanese woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) and exquisite Japanese carved ivories (okimono), some of which have been in storage for more than a century. “[Museum of Art director] Lynn Zelevansky has been interested in explaining how art from all over the world came to be located in Pittsburgh —the global-local connection,” says Louise Lippincott, exhibition curator and the Museum of Art’s longtime curator of fine arts, who has delved into the Museum of Natural History collections for two previous exhibitions, Fierce Friends: Artists and Animals, 1750–1900, in 2006, and last year’s Andrey Avinoff: In Pursuit of Beauty, which paid homage to the former Museum of Natural History director. Reaching into the natural history vaults again, she and curatorial assistant Akemi May assembled Japan is the Key, which opens March 30 and features 80 works, 69 from the Museum of Art and 11 from the Museum of Natural History. As the pair began to research the provenance of Japanese works acquired before 1920, they discovered that it was Heinz, the founder of the famous food dynasty, who connected Pittsburgh with the Asian empire.

Heinz, who made two extensive trips to Japan, recognized that the island nation was an emerging world power. “Japan is the key to the Orient,” he declared in a statement that gives the exhibition its title. The show spotlights an era when the West and Japan first met on common ground. The Meiji Reforms of the late 19th century had opened the country to more liberal ideas. In contrast to China, which experienced the Boxer Rebellion of 1898–1901, Japan welcomed American visitors, including a number of Pittsburgh industrialists. A series of world’s fairs subsequently brought Asian art to American cities, popularizing Japanese landscape and geisha prints, calligraphy, and delicate carvings. “From 1870 to 1920, there was a real fascination in Japan with the West,” says Lippincott. “They were intrigued by the military and industrial technologies of the West, while the West was captivated by Japanese art. There was mutual interest.” As Andrew Carnegie’s new “palace of culture” built its collections, Japanese prints, carvings, watercolors, and calligraphic poetry would become an early area of interest, reflecting the tastes of John Beatty, the first director of the museum’s fine arts department; William Holland, director of the museums; avid collector Heinz; and a flamboyant consultant named Sadakichi Hartmann.

“Hartmann came along at the right time,” observes Lippincott. “Beatty was interested in broadening the collection beyond paintings from the Carnegie Internationals. Hartmann was involved with the drawings collection and Japanese prints, so he was the catalyst.” A learning curve and deep pocketsHartmann was an enthusiast of Japonisme, but not, it turned out, an expert. In 1917, a Japan expert visited Carnegie Museums, and pointed out that a substantial number of Hartmann’s purchases were second-rate re-strikes. Beatty destroyed these prints. “Early on, the curators had energy, but they didn’t have all the facts,” notes curatorial assistant May. “Eventually, they got better. They learned to work with reputable dealers and sought out experts to evaluate works before they were purchased.”

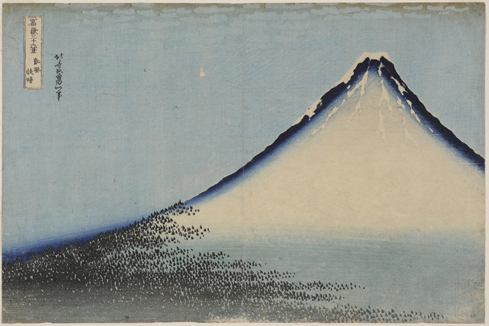

Edward Duff Balken, the museum’s first curator of prints and drawings, corrected course, purchasing dozens of important masterwork prints in 1916 and 1918. Katsushika Hokusai’s South Wind at Clear Dawn, included in the exhibition, is a rare 1830–31 version of his Red Fuji, one of the most famous ukiyo-e landscapes. “Heinz was the spirit behind the collections, especially the ivories.”

–Louise Lippincott, Curator of Fine Arts

Also among the prints and carvings included in the exhibition are a few more recently discovered duds.

Last year, when Chris Uhlenbeck, another Japan expert, began researching the objects on the show’s checklist at the request of the museum, he discovered several errors. The Apparition of Kannon by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, as it turns out, was not a stand-alone print but originally part of a triptych. Comparing it to another print in the series held by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, curators discovered that it was incorrectly colored. “The person who colored the blocks made up the colors, apparently,” says Lippincott. “We are going to hang onto it, but we’ll show a small reproduction of the Boston triptych so people can compare the images. We also footnote a couple of other single sheets that were supposed to be part of triptychs, and others where colors have faded.”

Deep-pocketed patrons with a real yen for Japan were indeed the key to Carnegie Museum’s early dominance in Japanese collections. Chief among them was Heinz (see sidebar), whose collection of fine ivory-handled canes was a personal trademark. Up to half of Andrew Carnegie’s annual gifts to the museum also supported the acquisition of Japanese prints and ivories. Irwin Laughlin, heir to the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation fortune, became a U.S. diplomat to Japan and brought lavish suits of Japanese armor and weapons back to Pittsburgh in 1909. Those items, along with the antique sedan chair Heinz purchased in Japan in 1913, eventually became part of the anthropology collections at the Museum of Natural History. “It’s a spectacular work of art.”

–Conservator Gretchen Anderson about the ivory eagleHeinz acquired another massive souvenir from an unknown artist in Yokahama: an ivory eagle, which he gave to the museum in 1913. With a wingspan of nearly four feet, this rare work crafted almost entirely of elephant ivory by an unknown artist has not been on view for more than 20 years. In preparation for its return to the spotlight, museum conservators spent weeks meticulously cleaning it, removing particulates from air pollution that accumulated during the city’s industrial past. Recent visitors to Carnegie Museum of Natural History may have spotted conservator Gretchen Anderson and conservation interns working on the sculpture inside a classroom in Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians. In 1913, the sculpture, which includes hundreds of ivory feathers, was valued at $5,000.

“It’s a spectacular work of art,” says Anderson, noting that it’s not carved completely from ivory. “We believe there’s a base of wood into which each of the carved feathers were attached.” Imperial schools that trained Japanese artisans of that day not only preserved an exacting and vanishing tradition; they inspired Western crafts to a new level, says Lippincott. The ideal of Japanese female beauty celebrated in prints translated into American art, influencing painters like James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Their iconic landscapes impressed the likes of Winslow Homer. Smaller items in the exhibition demonstrate extraordinary craftsmanship. Mirrors mounted below some of the figurines, such as Yuki Nobu’s Figure of a Young Girl and Boy with Puppets by an unknown carver, allow visitors to glimpse the hidden detail that extends even to the soles of the statues’ feet. The Artist Masayuki and the Seven Gods of Happiness depicts the legend of Masayuki (Li Tzu Ch’ang) seated in front of a screen, on which several carved figures cavort and come to life; the entire piece could fit comfortably in the palm of a hand. In Inro with Netsuke (Figure of a Frog) an unknown artist created a perfectly detailed amphibian the size of a marble. To Pittsburghers viewing them at the turn of the 20th century, the works in Japan is the Key illuminated an exotic contemporary culture. One hundred years later, those treasures testify to the role of one especially discerning and generous collector. “Heinz was the spirit behind the collections, especially in terms of the ivories,” says Lippincott. “The acquisitions would not have happened without him.” The Ketchup King and the King of the Bohemians

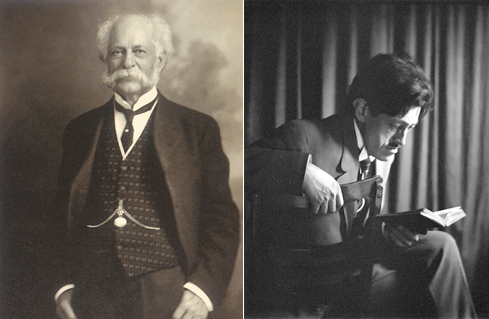

Could there have been a more unlikely pair of connoisseurs? Henry J. Heinz, a millionaire world-traveler and earnest Christian, and Sadakichi Hartmann, a colorful artist and critic, were the tastemakers who influenced some of Carnegie Museums’ first important art acquisitions. Heinz taught weekly Sunday school from age 12 until a few weeks before his death at 74. Believing that the Sunday school movement was “the world’s greatest living force for character building and good citizenship,” he carried his fervor abroad, becoming vice president of the International Sunday School Association in 1918. He visited Japan in 1902, learning about Sunday school missionary efforts there, and again in 1913. On both trips, he amassed treasures that he lent or gave to Carnegie Museums; later, he was named its honorary curator of ivories, timepieces, and textiles. “His vast collection was marvelous in variety,” wrote an admiring obituary, “and all aside from the beaten track, his unique timepieces and walking sticks with ivory heads of the most delicate carving being a special pride, all of his possessions being works of art, for he had infinite good taste and judgment in this regard.” Hartmann, who was of German-Japanese descent and arrived in the United States alone at age 14, served as a consultant for Carnegie Museum’s fine arts department director John Beatty in 1905–06. An eloquent writer on Japanese art, the self-educated poet and critic befriended Walt Whitman, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Ezra Pound in New York. At 23, he wrote his first play, Christ, which was banned in Boston and publicly burned after Hartmann’s arrest for obscenity. He lost a clerical job with famous architect Stanford White after publicly describing his employer’s drawings as “to be improved upon only by the pigeons, after the drawings become buildings.” Never averse to attention, Hartmann was crowned “King of the Bohemians” by a Greenwich Village promoter. John Barrymore described him as “a living freak... sired by Mephistopheles out of Madame Butterfly.” The actor’s hyperbole ignored Hartmann’s stature as an influential critic and champion of Modernism. He was one of the first critics to write about photography, with regular essays in Alfred Steiglitz’s Camera Notes, and he wrote some of the earliest English-language haiku. During his brief sojourn in Pittsburgh in 1905–06, he laid the foundations of the Museum of Art’s Japanese print and American drawings collections. Heinz died in 1919. Hartmann went west, where he remained until shortly before his death in 1944. He continued writing and even played the court magician in Douglas Fairbank, Sr.’s silent swashbuckler, The Thief of Bagdad, in 1924. His terms: $250 and a weekly case of whiskey.

|

||||||||||||||||

Under the Influence · The Shape of Things · Creatures of the Wild · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nina Marie Barbuto · Artistic License: Permantly Interesting · Science & Nature: Survivor's Tale · About Town · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |