|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Photo: Tom Little |

The Shape of Things

From its start, the Heinz Architectural Center has challenged visitors to think about how the built environment impacts their lives.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the Heinz Architectural Center, which from its inception has aspired to get the public to “think about it”—to ponder how the built environment is created and why. Designed by Cicognani Kalla Architects in New York, the center was a gift of Drue Heinz in honor of her late husband, Henry J. Heinz II, who had had a nearly lifelong interest in architecture. At the time the center opened, it was one of the most substantial facilities devoted to architecture of any art museum in America—with exhibition galleries, offices, a library, and collection storage rooms. In 1993, then museum director Phillip M. Johnston wrote confidently that the Center’s opening “inaugurates a new era in the history of Carnegie Museum of Art.” For two decades, a series of curators have presented three exhibitions per year, an ambitious undertaking exploring the world of architecture from standpoints theoretical and material, historic and contemporary, regional and worldwide. But in fact, architecture has been an important part of Carnegie Museums for much longer. In 1890, Andrew Carnegie gave the City of Pittsburgh $1 million to build Carnegie Library, Museum, and Music Hall. A year later, he held the largest architecture competition in the United States—garnering 101 submissions—to select the site’s designer, the architects Longfellow, Alden & Harlow, a firm based in Boston and Pittsburgh. From the very outset, the institution endorsed the notion that architecture was a valuable form of expression.Decades later, Leon Arkus, director of the Museum of Art from 1968 to 1980, invited 18 famous architects from around the world to donate drawings. Works received from modernist Richard Neutra and former Carnegie Mellon dean of architecture Paul Schweikher became precursors to the center’s collection today. There was also the established legacy of the Heinz family. Henry J. Heinz II, the grandson and namesake of the famous ketchup magnate, was an amateur architectural photographer, and he and Drue funded the gallery at the Royal Institute of British Architects that opened in 1972. “When you see all these pieces together you think, ‘Why wouldn’t we have an architecture department here?’” says co-curator Tracy Myers, who arrived at the museum as assistant curator in 1997. In 2003, it became clear that the Heinz Architectural Center’s nonstop production cycle required two full curators, separate but equal. That year, Myers, who worked in finance and the legal profession before turning to the arts, was named curator along with Raymund Ryan, an architect and critic from Ireland. The pair, thought to be highly complementary for their disparate backgrounds, has worked side-by-side at the center for the past decade. Most recently, the curatorial team created 20/20: Celebrating Two Decades of the Heinz Architectural Center, now on display, which uses the lens of storytelling to explore the center’s history, highlight the gems of its collection, and engage its public in new dialogues about what architecture means to them.

Architecture for allIn 1993, a press release announcing the opening of the Heinz Architectural Center described its mission “to further the appreciation and understanding of architecture” and explore “the full range of past architectural expression as well as issues of current concern to the profession.” Myers and Ryan will tell you this mission is still essentially the same, but it must reckon with two major changes in the environment in which it functions. First, the definition of the word “architecture” is different, broader, than it used to be.

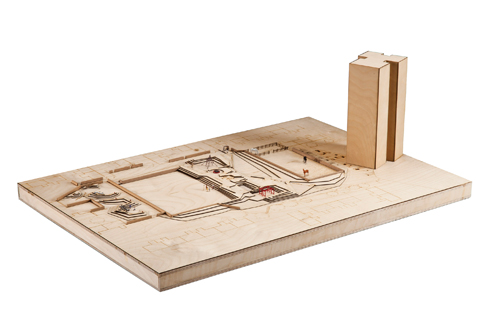

“It’s not just about architecture on a pedestal as a beautiful abstract object. It’s something more,” says Ryan, who in recent decades has seen the disciplines of art, architecture, and other forms of design become increasingly intertwined. In 2012, for instance, two of Ryan’s exhibitions (Maya Lin and White Cube, Green Maze: New Art Landscapes) explored an intimate fusion of architecture and landscape design— from room-sized installations evoking mountainous topography to the model of a Seattle sculpture garden that spans a highway and connects the city to its waterfront. This pairing of disciplines gained momentum from the growing green agenda of the past decade, Ryan says. But other, less expected specialties inform architecture, as well. In 2008, Dutch MacDonald, a Carnegie Mellon University-trained architect, left the field after nearly two decades to enter a broader conversation about design. “I was trying to grapple with what was happening in the world,” says MacDonald, now chief operating officer at MAYA, a Pittsburgh design consultancy. As we become a mature society, MacDonald suggests, solving complex problems requires working across disciplines. Some of today’s biggest architecture firms, for instance, have staff researchers in fields like psychology, ethnology, and anthropology. “What if I invited an ornithologist to work on an urban design project?” MacDonald asks. “All of a sudden, I’m going to get a perspective about wildlife in the urban environment I’ve never had before.”

The second development that has to be accounted for in evaluating the Heinz Architectural Center’s mission, according to Myers, has to do with its audience. When the center opened its doors, it quickly became a valued resource, a dedicated space for local architects and design devotees to view new and interesting work—before the Internet and social media made information-sharing a breeze. The fine-tuning here, Myers says, is that the center can’t be just about serving the practitioners of architecture. “We’re a museum,” she says, “So our audience is the general public.” And the way in which the general public likes to receive information has changed dramatically. Partly due to the explosion in the use of social media, visitors to public institutions now crave not a lecture, but a dialogue. “This really is a paradigm shift,” says Myers, who explains that the museum world at large is facing the same transformation. Until 10 or 15 years ago, she says, professionally trained curators were the unquestioned experts; they’d write labels and texts for objects and exhibitions implying, this is what you need to know. “But now people are saying, ‘Yeah, but that’s not what I’m interested in,’” says Myers. As the public has become more knowledgeable about architecture and other forms of design, so, too, do they want to weigh in on its importance. “It’s not just about architecture on a pedestal as a beautiful abstract object. It’s something more.”

– Raymund Ryan, Curator of Architecture

Visitors to public institutions now crave not a lecture but a dialogue. “This really is a paradigm shift.”

– Tracy Meyers, Curator of Architecture

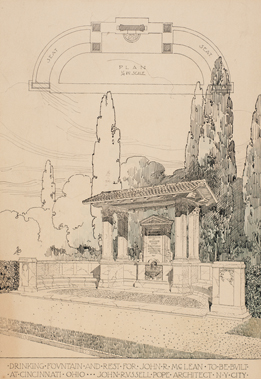

When a Pittsburgh executive looks out the window of his company’s Downtown office building, he can see a strange lantern-like structure glowing on the corner, at 600 Liberty Avenue. It’s a piece of the PNC Legacy Project, which houses a multimedia museum of Pittsburgh history. The building reminds him of Pittsburgh’s eclectic, industrial past: Diverse people clustered together taking an attitude of, “You’re going to work hard and do something? Go ahead. I’m not going to stop you.” This is a creative city, he thinks, one unafraid of taking risks. A lasting impactOne of the most important roles of a museum curator, Myers says, is building his or her department’s collection. Today the center owns more than 5,000 objects— predominantly American—including drawings, models, photographs, rare books, commemorative objects, and even architectural toys, made between the 1780s and the present. For the most part, collecting is a calculated art: curators carefully assess how each new object strengthens the collection and fills in its gaps. But all the while they’re unavoidably subject to the personal way in which certain objects “speak” to them, Myers says. It’s this latter, gutfeeling inspiration that serves as the focus of the two galleries in 20/20 devoted to a small but representative sample of 20 objects from the center’s collection. Alongside each item appears a statement by a current or previous curator, suggesting why the item is a “must-have.” Among the gems exhibited is a print—blue ink on linen—of the original design by Longfellow, Alden & Harlow Architects that won Carnegie’s 1891 competition for Carnegie Library and Museum. The dominant image on the drawing shows the Music Hall seen from Forbes Avenue, with two domes over the entrance and two towers flanking the hall itself. (These were removed for the addition completed in 1907.) The rendering includes incredible detail, complete with cornices drawn to imply delicate ornamentation on stone. Yet, the lettering inscribed above the entrance reads, casually, “There will be an inscription carved here.” (“I just love that,” Myers says.) Until recently, the drawing was one of more than 800 stored in an old wooden filing system in the museums’ facilities, planning & operations department before being turned over to the center for safekeeping. When Myers looks at the drawing, she imagines Carnegie in the 19th century, sitting, pondering, and then exclaiming, That’s the design! One of Ryan’s favorites among the 20 objects on view is a drawing by American architect Paul Rudolph of the Yale Art and Architecture Building (facing page, top right) in New Haven, Connecticut, where Ryan received his master’s degree. It’s an American example of Brutalism —a style of modern architecture favoring linear, concrete, blockish structures. The Yale building is perhaps Rudolph’s masterpiece, with a complex floor plan that clusters vast open spaces among 37 different levels on nine floors.

“It’s a building that some people love and some people hate,” says Ryan. When he sees the drawing, it reminds him of an experience he had one day in the 1980s, when, as a student on campus, he exited the building to encounter French philosopher Jacques Derrida, the thinker most associated with Deconstruction. “He was there with three other people and they couldn’t find their way into the building. They kept trying to open the fire escape. I had to explain, ‘No, no, no!’” says Ryan, chuckling to think that a man with such difficult-to-navigate ideas would himself be confounded at the entrance to another man’s modern design. The idea that stories like these add depth to our understanding of the built environment is not lost on Myers and Ryan. In fact, 20/20 devotes the center’s largest gallery to a project conceived by ThoughtForm Inc, their consultant collaborators on the exhibition: video documentaries of everyday people telling stories about experiences they’ve had in which the built environment has had a dramatic influence in their lives. People like Dave Sobal, journalist Patricia Lowry, and executive Dutch McDonald. It will be a continuously growing collection of stories in which visitors are encouraged to participate—and further evidence of the new era of the Heinz Architectural Center, which keeps in mind one curator’s favorite quote from Winston Churchill: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Under the Influence · Creatures of the Wild · The Carving Out of a Collection · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Nina Marie Barbuto · Artistic License: Permantly Interesting · Science & Nature: Survivor's Tale · About Town · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |