|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Above: Matt Lamanna (second from right) and colleagues explore the Cape Lachman area of James Ross Island. |

Southern Exposure

Carnegie Museums’ chief dinosaur hunter leads the charge in a race to reveal the secrets of one of Earth’s last great frontiers. Departing from southern Chile on a sunny day in February, Matt Lamanna boards a 230-foot research vessel bound for the frozen end of the Earth. Although the distance between the southern tip of South America and the Antarctic Peninsula (the prong of Antarctica that juts north toward South America) is less than that from Pittsburgh to Chicago, the voyage took four days, the ship inching slowly across the Drake Passage, the roughest stretch of water in the world. This isn’t the first trek to Antarctica for Lamanna, assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and his research team. And they know that getting there is just half the battle. To set up camp on Vega Island, just east of the peninsula, the eight scientists hop aboard small, motorized inflatable boats called Zodiacs. If thick layers of sea ice have formed along the shorelines, as they did during the group’s 2009 visit, the Zodiacs won’t reach their destinations, and the long journey to the end of the world ends as a bust. On this day, even when they reach their target, the researchers know that snow squalls and hurricane-force winds could whip up at any moment, wreaking havoc. So goes a day in the life of a fossil hunter in Antarctica.

Will the trip be worth it? The determined team of researchers remains undaunted. What they’re in search of goes way beyond mere fossils. They’re hoping to piece together the mysterious environment of an ancient Antarctica, and the intriguing role it played in the history of the planet. With a bit of luck and a lot of perseverance, over the next several weeks Lamanna and his colleagues find two of the 10 or so non-avian dinosaur fossils ever discovered there from the Cretaceous Period (145.5-65.5 million years ago). Not to mention some of the best fossil evidence that traces the origin of modern birds to the Age of Dinosaurs, and just maybe a new species of long-necked marine reptile known as a plesiosaur. All in all, they bagged 200-plus fossils. “What we’ve found so far, it’s like the trailer to the movie,” says Lamanna, who is the lead investigator on a newly awarded National Science Foundation grant that will fund the upcoming 2013 and 2014 field seasons. “Enough to get you excited, but not even close to the whole story.”

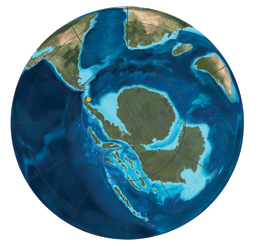

In the months and years ahead his team will be continuing its interdisciplinary research, including the study of Cretaceousaged birds, marine reptiles, fishes, plants, and the ever-elusive non-avian dinosaur and mammal fossils. And because Lamanna is the lead investigator, all fossil discoveries will eventually end up in Pittsburgh. “There’s only so much you can learn from one dinosaur toe bone; there’s only so much you can learn from an isolated tooth,” Lamanna notes. “But more important is the encouragement that these fossils provide. They show that the area still has secrets to yield. Not a lot is known about Antarctica at the end of the dinosaur era, so the potential significance of almost anything we find is just huge.” Most of the world’s best-known dinosaurs—T. rex, Diplodocus, Velociraptor, Triceratops —hail from North America or Asia. But, as Lamanna is quick to point out, dinosaurs also thrived elsewhere, and many of them differed dramatically from their more northerly cousins. So the 37-year-old paleontologist has spent the past 15 years on the hunt in remote regions of Argentina, Australia, Egypt, and now Antarctica, in search of the mysterious dinosaurs of Gondwana, the supercontinent that broke apart about 100 million years ago to form the landmasses of today’s Southern Hemisphere. A few years ago, Lamanna and a different set of collaborators unearthed one of their biggest discoveries to date in the Patagonia region of southern Argentina: a nearly complete skeleton of a probable new species of 100-foot-long, 40-ton-plus titanosaur, a type of long-necked, plant-eating sauropod dinosaur. One of the largest land animals that ever lived, its fossilized remains were meticulously prepared in the Pittsburgh museum’s PaleoLab. Along with other important new dinosaur discoveries from Patagonia, as well as the long-sought fossils from Antarctica, Lamanna hopes that the titanosaur will help to decipher major events in Earth’s history. Specifically, how Gondwana broke apart, and how this radically shifting geography influenced dinosaur evolution and extinction. “I want to know what kinds of dinosaurs lived in Antarctica,” he says, excitedly. “Were they closely related to those living in South America? How do they compare to those from Australia, and so on? There are tantalizing clues that there was some form of land connection between South America and Antarctica at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. One of the best pieces of evidence for that is a single tooth.”

That tooth, discovered in Antarctica by a team of Argentinean and American scientists in the 1990s, comes from a hadrosaur, a type of land-dwelling, plant-eating dinosaur more commonly known as a duckbill. The only other place in the Southern Hemisphere where duckbills have been discovered is South America. “All the evidence indicates that hadrosaurs evolved in the Northern Hemisphere, then migrated to South America, and from there to Antarctica,” explains Lamanna. “Since we don’t think they could swim across oceans, that implies there was a land connection—or at least a chain of closelyspaced islands—between South America and Antarctica during the Cretaceous. “At the end of the day, it’s about trying to reconstruct these lost ecosystems, trying to figure out what was living in Antarctica at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs,” Lamanna continues. “That’s the first step toward unraveling the role that the continent might have played in shaping modern plant and animal distributions.” The worthwhile gambleBefore heading into a deep freeze about 40 million years ago, Antarctica was sandwiched between South America and Australia as part of Gondwana. As the supercontinent separated, land bridges or perhaps a series of islands likely remained for millions of years, making Antarctica an important crossroads for animals some 80-45 million years ago, the time when mammals rose to dominance as non-avian dinosaurs went extinct. The exact timing and sequence of events is still a hot topic of debate.

While Antarctica has remained at much the same latitude for the last 100 million years, scientists believe that during the Cretaceous Period it boasted a much warmer, even lush environment. Fossils unearthed on the same series of islands off the Antarctic Peninsula that Lamanna and his team are prospecting—the four main islands of James Ross, Vega, Seymour, and Snow Hill—include not just dinosaurs and birds, but also fishes, marine reptiles, and even ancient leaves, wood, and seeds that together reveal an Antarctica with a subtropical climate, says Ross MacPhee, the curator of mammals at the American Museum of Natural History in New York who will make his sixth trip to the continent this coming February as part of Lamanna’s team. MacPhee, who sparked Lamanna’s passion for Antarctica with an expedition invitation in 2009, is particularly interested in the history of Australian marsupials, believing that their ancestors emerged in South America and traveled across Antarctica to Australia about 80 million years ago. The only way to know exactly what role Antarctica played? “Put boots on the ground, and find out for ourselves,” he says. Lamanna says MacPhee is “hell bent” on finding the first Cretaceous mammal on the continent. “All the biogeographical indications are that mammals had to be there,” says MacPhee. “It’s still a total crap shoot and risk, but that’s all beside the point. We’re all gamblers in this line of work. I hope it happens this season. Or maybe next. The point is you have to be there.” As any paleontologist will tell you, field work can be painfully slow and often frustrating. In Antarctica, the obstacles are multiplied by the elements, with almost everywhere except the James Ross Island Group covered by ice a mile thick, yearround. Those islands, which are among the few places where researchers are able to search, are dominated by marine deposits, meaning that fossils of land animals are going to be scarce. “Usually, when I’m looking for dinosaurs, fossils of land-living things are the only kind that I see on the ground,” says Lamanna. “If I’m walking in Patagonia and I see a fossil, there’s a good chance it’s either a piece of petrified wood or a dinosaur bone.” In Antarctica, Lamanna’s mental “fossil alarm” goes into overdrive, but not in a good way. “If you do enough prospecting, your eyes eventually get trained to recognize biological forms on the ground,” he explains. “It can be frustrating to work in Antarctica because the rocks we look in were laid down in an ancient ocean and are loaded with remains of the things that lived there. My fossil alarm is constantly going off, but 999 times out of a 1,000, it’s nothing worth picking up.”

And that’s hardly the only frustration. On most days of the 2011 expedition, temperatures climbed into the 40s during the day and didn’t typically dip below 20 degrees in the evenings. But the wind could be fierce, with sustained speeds of more than 60 miles per hour. And because temperatures hovered right around freezing, clothing and supplies would constantly melt and refreeze. “It ranged from sunny and beautiful to snowy to ridiculously windy. The wind was the worst,” recalls Lamanna. “Imagine sleeping outside in canvas tents during Hurricane Sandy,” adds Julia Clarke, a fellow paleontologist and the team’s lead bird expert. “On top of that, if you get your feet wet, or sweat, you never get dry.” The cradle of modern birds?Lamanna and team, which also included a geologist, another mammal paleontologist, a fossil crocodilian expert, and a paleontology graduate student, spent much of their recent five-week field season at a camp on Vega Island, just north of James Ross Island. In the early 1990s, Vega yielded one of the most significant fossil finds in bird evolution. In 2005, Clarke led a team that conducted a detailed analysis of the extinct species, Vegavis iaai, which was collected by Argentinean geologists. Clarke and team determined it to be a close cousin of ducks—and, in doing so, proved that at least one lineage of modern birds coexisted with dinosaurs.

In 2011, Lamanna, Clarke, MacPhee, and colleagues recovered some 25 isolated bird bones and at least one partial skeleton in a rock concretion on Vega Island—one of their most important finds of the field season. “There’s pretty compelling evidence that the modern bird group originated during the Cretaceous,” Lamanna says. “The exciting thing is that the only undoubted Cretaceous fossils of modern birds all come from Antarctica. So that raises a very interesting question: Is it possible, just possible, that every single bird we see flying around us today traces its ancestry to Antarctica towards the end of the Age of Dinosaurs? To Antarctica, of all places—a place that today is a frozen wasteland where hardly anything lives?” Other notable finds include teeth and bones from sharks, marine reptiles, a diverse collection of fossil plants, including a winged seed that resembles those of modern maples, a new species of fossil crab, and of course the pair of dinosaur fragments, both uncovered in an area known as the Naze Peninsula on James Ross Island. “We only spent about eight hours on the Naze, with five people, so in 40 man-hours of looking we made two dinosaur finds, which is pretty damn good by Antarctic standards,” says Lamanna. To date, there’s evidence of six major dinosaur groups living in Antarctica at the end of the Cretaceous Period. But all of the fossils are fragmentary, ranging from about 50 poorly preserved bones from one animal to a single bone for others. So a relatively complete skeleton of a dinosaur would be a major discovery. That’s why, in less than three months, Lamanna will be back on the Antarctic Peninsula, setting up camp on the Naze. “It’s an entire continent for which we know almost nothing, and that’s what makes it so exciting,” says Lamanna. “It’s like when Andrew Carnegie sent his expedition out to Wyoming in 1899, or even before that, when people like O.C. Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope were exploring the American West and finding new dinosaurs left and right. “I’m not saying we’re going to equal that productivity, or even come close, but Cope and Marsh were providing our first insights into the dinosaur fauna of an entire continent. And that’s what we have the opportunity to do in Antarctica.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Our Place in Space · Breaking Out of the Cube · Reimagining Home · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Tina Kukielski · Artistic License: Hacking Reality · Science & Nature: Going Buggy · Field Trip: Where in the World is Carnegie Museums? · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |