|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

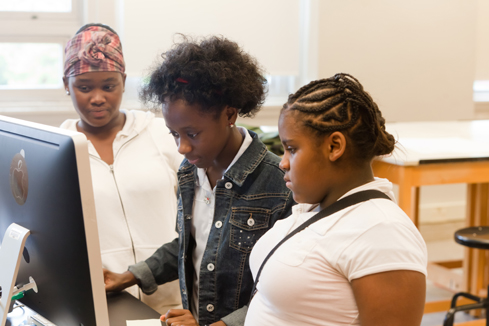

Photography by Renee Rosensteel |

Reimagining Home

Can arts education help a new generation find inspiration in their distressed community? The Warhol and Pittsburgh Public Schools aim to find out. Two iconic Pittsburgh innovators, Andy Warhol—the museum—and George Westinghouse—the Pittsburgh public school—are teaming up to infuse art into a struggling community. As part of The Andy Warhol Museum’s ongoing artist-in-residency program, The Warhol at Westinghouse initiative found its spark in Alisha Wormsley. A Pittsburgher herself, the 34-year-old brings her multi-media, photography, teaching, and writing experiences directly into the classroom, sharing her knowledge with the school’s sixththrough 12th-graders. The year-long partnership provides rare opportunities: small class sizes, lots of one-on-one interaction, and field trips to The Warhol. But in many ways it’s still a work in progress, says Nicole Dezelon, The Warhol’s associate curator of education for school and teacher programs. “It really is a pilot, a new adventure,” she explains. “We have artists going into our partner schools, but they’re shorter term. This is more substantial. This is a community that is in significant need right now.” The community is Homewood. The need is for revitalization. “I live just a couple miles away in Garfield,” says The Warhol’s director Eric Shiner, “and I realized no one was talking about the visual arts in Homewood.”

Shiner decided to try to change the conversation. So, when The Warhol received a $10,000 Sprout Fund Seed Award, he asked two artists—Tina Brewer and Vanessa German—to create an installation specifically for Homewood. Their collaboration resulted in the installation, Home, and this past March it made its public debut at Frankstown Avenue’s Greater Pittsburgh Coliseum. “More than 200 people came to the launch party,” Shiner says, “and the common refrain was, ‘this is really cool to have art in our neighborhood.’” In the big scheme of things, art may not seem to rank high on the list of priorities for an area that has been in a free fall for decades. But according to Shiner, “art has a track record of breathing new life into a community.” Think Braddock, Pa., as an example in the making. And like Braddock, Homewood has an amazing past. It’s that backstory that truly piqued Shiner’s interest. “Knowing the history of a place,” he asserts, “is critical to figuring out what its future might be.” Nearly 100 years ago when Pittsburgh Westinghouse first opened its doors, Homewood was all about the hustle and bustle. It was a destination, a hub for trains and trolleys. It was where wealthy industrialists and entrepreneurs, like Andrew Carnegie and George Westinghouse, built their homes (aka mansions). It was also where upper middle class African American families, as well as working class Irish, Italian and Germans lived, together. Talk about a melting pot. But the pot got stirred in the 1950s. As the city proclaimed the Lower Hill District a perfect location for a new arena, some 8,000 people lost their homes, many resettling in Homewood. The subsequent “white flight” left the neighborhood nearly 70 percent black. Then in the aftermath of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, Homewood (like the Hill District, the North Side, and black neighborhoods in major cities across the country) was consumed by riots. Businesses were burned and looted. The community never truly recovered. Its population plummeted from 30,000 in 1950 to less than 7,000 in 2010. Today, nearly 30 percent of its homes are vacant, a reality that adversely and dramatically impacts property values. Finding their storyLocated on North Murtland Street, Westinghouse stands as a monument to education. It is a formidable structure meant to last, to survive, to maintain a sense of constancy even as the world around it changes. But ultimately, bricks and mortar cannot withstand the pressure of budgets stretched to their very limits. And as is often the case, one of the first casualties of reduced resources is the arts. Just last year, the school suffered the loss of administrators and faculty, including an art teacher.

The Warhol sought to fill that void. “In my opinion,” says Westinghouse’s project manager Caroline Babik, “any program that allows students to explore the arts is needed. It’s an outlet for many students to express themselves and share their thoughts and ideas. It creates a different space to help them figure out where they belong in the world and gives them self-confidence.” And Shiner was confident he knew just the right artist for the job. “Alisha is the perfect person to go in and work with the kids,” he says. “She’s a collaborative artist by nature and a great mentor.” At the time, Wormsley was a working artist living in Brooklyn. The path she’s traveled back to Pittsburgh has not exactly been a straight line. After graduating from Winchester Thurston High School, she enrolled at Fordham University with a goal of becoming a doctor, joining the Peace Corps, and delivering babies all over the world. Instead, she dropped out of school and explored Europe for six months. Upon her return to the States, she signed up to study at the University of California, Berkeley, where she earned her master’s degree in anthropology. Nowadays, Wormsley describes herself as a visual anthropologist. “Most of my work focuses on folklore and history,” she says. “I’m a storyteller.” That realization has led her to take on the role of teaching artist at various cultural institutions, including The Studio Museum of Harlem, the Children's Aid Society, The Romare Bearden Foundation, the International Center of Photography, and the August Wilson Center for African American Culture. It was at August Wilson that she first met Shiner. “We started talking about different ways to bring contemporary, progressive art to Pittsburgh,” Wormsley recalls. To that end, Shiner invited her to participate in The Warhol’s 2011 Biennial. From there, it was a short trip to The Warhol at Westinghouse, sort of.

Wormsley’s arrival at Westinghouse last spring marked the end of her Reverse Migration Project, which took her from Pittsburgh to the Appalachian Mountains to Virginia to North Carolina to South Carolina to Barbados to Cape (Slave) Coast to West Africa and back to Pittsburgh. Bringing with her the images she captured and the journals she kept along the way, it also served as the starting point for her tenure at the school. Her project became the catalyst for her students to think about what they might create. “We talked about the similarities between Africa and Homewood,” she says, “and we talked about breaking down stereotypes.” "This is their only opportunity to have art. THere's a lot of energy, it's inspiring. I'm inspired by the kids."

- ALISHA WORMSLEY, TEACHER AND MENTOR, THE WARHOL AT WESTINGHOUSEShe had the kids make a list of their expectations of what Africa in general and Ghana in particular are all about. Their tally included lions, safaris, poverty, and war. When Wormsley shared her photographs, what they saw were cities and schools like theirs. Hairstyles and clothes that looked a lot like theirs. They saw that everyone— from the very rich to the very poor—was black.

With Wormsley gently guiding them through the process, the kids made their own movies. (These short films will debut on The Warhol website sometime soon.) “Here most black films are based on reality,” she says. “There’s a lot of mythology and fantasy in African films, and that changed their ideas of what they could make.” What they made ranged in topic from alien invasions to whodunits, but they all had one thing in common. “The part that amazed me,” Babik says, “was seeing a finished product that included a script, characters, and working together as a team. Alisha helped them make imagination into finished, quality products.”

Wormsley adds, “Being an artist doesn’t mean you can draw or paint. It’s the ideas. All you have to do is have ideas.” "She engages and challenges her students. The kids say it's one of the hardest classes they take."

- Kilolo Luckett, Former project manager of The Warhol at WestinghouseBut as a teacher, you also need to have persistence and patience—two qualities she exudes, affirms Kilolo Luckett, The Warhol’s director of development. “She engages and challenges her students,” says Luckett, who has helped coordinate the many components of The Warhol at Westinghouse. “The kids say it’s one of the hardest classes they take.” Oodles of inspirationThe main doors to Pittsburgh Westinghouse open to reveal a control room where security monitors keep an unwavering watch on hallways and exits, and nearby metal detectors stand guard. The first-floor walls are lined with nearly 100 photographs of role models: alumni who have found success in fields ranging from politics and business (State Representative Joe Preston and The Urban League’s Esther Bush) to sports and music (the NBA’s Chuck Cooper and jazz musician Billy Strayhorn).

Back in its heyday of the 1950s, the school boasted some 1,500 students. Today enrollment is less than half of that. As the bell rings (actually it’s more like a buzzer), 14 sixth-graders rush in to room 312. They’re excited. They had to sign up specifically to take this class, and there was a waiting list. “This is their only opportunity to have art,” Wormsley says. “There’s a lot of energy, it’s inspiring. I’m inspired by the kids.” Dressed casually in jeans, red rain boots, a green V-neck t-shirt and black sweater, she greets her students. Urging everyone to take a seat, she begins with a quick refresher. “Who am I?” she asks. “Miss Alisha,” the kids respond. “What do I do?” “Take pictures, edit things, make collages, make films.” “Who sent me?” “Andy Warhol!”

From there, Wormsley starts to draw a connection between Warhol and Pop art and today’s pop stars, pop culture, and colors that pop. “What’s popular now?” she asks. The kids raise their hands and the answers come fast: “James Bond,” “Adidas,” “braids,” “Katy Perry,” “Drake,” “Will Smith,” “piercings,” “Hello Kitty,” “Tony Hawk,” “Coogi jackets,” “Troy Palamalu,” “Apple computers,” “Nicki Minaj,” “frohawks.” She then breaks out five new, right-out-of-thebox digital cameras and encourages the students to explore the environs of the classroom and take photographs of anything that looks like pop culture. The room is not exactly bursting with stuff; it’s pretty plain. There are long tables, stools, several Mac computers, and a supply closet noticeably lacking supplies.

The kids turn the lenses on themselves—their sneakers, their hair, their backpacks. They look out the windows and perhaps see their neighborhood in a different light. “I think it’s very encouraging for the kids to know that Homewood was really great and can be great again,” Shiner says. “And they can be a part of that.” The Warhol at Westinghouse initiative is powered by support from The Jack Buncher Foundation, The Heinz Endowments, The Pittsburgh Foundation, the Virginia A. McKee Fund as administered by PNC Charities Trusts, First National Bank, and People’s Gas.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Our Place in Space · Breaking Out of the Cube · Southern Exposure · Directors' Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Tina Kukielski · Artistic License: Hacking Reality · Science & Nature: Going Buggy · Field Trip: Where in the World is Carnegie Museums? · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |