|

||||||

|

|

Picturing Me

Carnegie Museum of Art helps area youth discover how photography can help them explore Pittsburgh’s past and present and envision their place in its future. Flanked by nine elementary school students, photographer Kenneth Neely takes a trip into Pittsburgh’s past. “Check out what people are wearing,” prompts Neely. “They put on suits and got dressed up to go out. And hey, have you ever seen one of these?” he asks, pointing to a 1937 Cadillac Fleetwood. Transporting the group to the 1930s–1970s version of their hometown are nearly 1,000 black-and-white images by legendary photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris, on view at Carnegie Museum of Art through April 7. Because of the way the photographs are displayed— first as life-sized projections and then in row upon row of snapshot-sized prints that literally circle a second gallery—the mostly fourth and fifth graders are immersed in Harris’ native and incredibly vibrant Hill District as he saw it during the Jim Crow and Civil Rights eras, a foreign time to these students from Pittsburgh Lincoln K-8 in East Liberty.

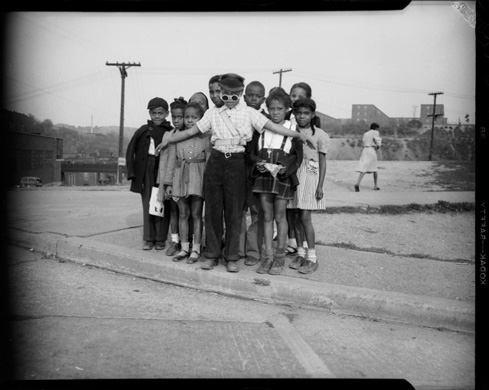

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Boy school crossing guard, 1947, Heinz Family Fund, Teenie Harris Archive © 2006 Carnegie Museum of ArtAmong the extraordinary people Harris photographed—entertainer Lena Horne, baseball legend Jackie Robinson, and change maker Martin Luther King Jr.—Neely points out the everyday Joes, and the important moments that make up a life and a neighborhood. Kids at the swimming pool. Sandlot baseball players. First birthday parties and young couples on their wedding days. He also talks a little shop, giving pointers about the basic elements of photography, including composition and lighting. “Every time you pull your camera out, you want to think about where you want your subject to fall—far right, far left, or middle,” he says, using Harris’ images as examples. “What do you want more emphasis on and less emphasis on? Do you want to use your flash? Do you want the shot to be candid versus posed? Me and you, we have lots of choices as artists.”

“That’s the beauty of this program. It’s more than just a day trip. It’s a full learning experience.”

- Michele Evans, Fifth-grade teacher South Butler School District Neely explains that, like Harris, he once worked for Pittsburgh’s black newspaper, now known as the New Pittsburgh Courier. And within just a short walk of the Teenie Harris exhibition, he’s able to share with the group examples of his own photography, also hanging in the museum in the exhibition Picturing the City: Downtown Pittsburgh, 2007–2010. In contrast to Harris’ work, the Picturing the City images are almost exclusively in color and the majority shot digitally. They highlight the people and places of today’s Pittsburgh through the varying lenses of nine Pittsburgh-based freelance photographers. As they walk, the students eagerly pepper the North Side native with questions about his background, how he seems so familiar with the people and places of their neighborhood, and what it’s like to make a living as an artist. One question is particularly poignant: Does he feel differently now that his work is in a museum? “As an artist, it’s a big achievement, but I create work for people to have in their homes,” Neely says, “so I’d be just as excited if it was up in your house. Having work in the museum doesn’t change my approach as an artist. I just want people to see my work.”

Fifth graders from South Butler School District explore the museum’s pair of photography exhibitions and then produce their own art.Photos: Jim Judkis

“If you take photos of a place now and take photos of the same place 10 years from now,” he says, “you’ll be amazed at how much things change. Photos help us keep track.” In large part, that’s the point of the visit: getting young people to recognize the value of photography as a way to record history— including their own. This intimate, artist-led tour is a highlight of Picturing Me, an initiative supported by The Heinz Endowments and developed by the Museum of Art’s team of artist-educators who meet with underserved youth in grades 3 through 12 at their regular after-school programs around the city. It’s one of two outreach programs designed by Museum of Art educators to help area students explore how photographs characterize a moment in time, how they can help shape our vision for the future, and how we can use them to understand and exchange ideas. The second program, Pittsburgh Past– Pittsburgh Present, is a six-month-long initiative supported by The Grable Foundation that reaches area students and teachers through museum field trips, studio workshops, professional development for teachers, and classroom extensions. “You know your neighborhood better than anyone,” Neely tells the students. “Walking from your house to the bus stop in the morning, or walking to the store, photograph what you see, the people and places you encounter. You can help paint the picture of your neighborhood.”

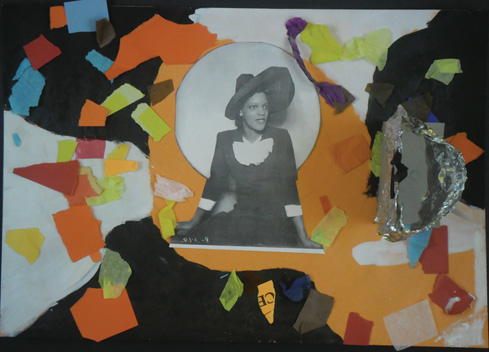

Past meets presentDuring a late December Pittsburgh Past– Pittsburgh Present field trip, a dozen 9- and 10-year-olds from South Butler School District in Saxonburg crowd around a single Teenie Harris image, a favorite selected by their classmate, Rachel. It’s a photograph of an older, seated woman and two attentive young girls. “Really look at the image,” urges Emily Croft, Carnegie Museum of Art’s coordinator of school studio programs. “Use your observation skills to find clues that will help reveal the story behind the photograph.” “Their age difference could mean she’s their grandmother,” notes one student. “The wallpaper looks old,” adds another. “They’re probably at her house.” The group also notes that while at first glance it appears the young girls are handing the woman something, upon closer inspection they’re simply gesturing toward her. After exhausting all visual clues, they head to the computer to do a little more research by way of the Teenie Harris Archive, learning that the older woman is a former slave. The intimate moment was captured between 1950 and 1955. In a nearby gallery, another 10 of the 42 fifth graders wearing matching green and blue tie-dyed t-shirts are exploring the images of Picturing the City. As they soak in the sights of modern Pittsburgh, they talk about exposure, point of view, and composition. An image by Dylan Vitone of the 2009 Stanley Cup victory parade puts the viewer in the middle of a giddy throng of Penguins fans. “It’s like a flip book,” says 10-year-old Nathaniel, noting that the panoramic image reflects an unforgettable scene he witnessed firsthand. Vitone could have captured the action in a single photograph; instead he chose to piece images together, overlapping them slightly. “What kind of effect does it have?” an educator prompts. “It makes the image feel fast,” says Nathaniel. After exploring the exhibitions, the students pile into one of the museum’s art-making studios. Dozens of photocopies of photographs from the pair of exhibitions cover the tables. Nudged to consider elements in an image that are clues to whether it’s from the past or present, students are set free to create their own image in a collage. “Now you have the freedom to make the choices and narrate your own story,” encourages artist-educator Deanna Mance. “Feel free to play with point of view.” One boy pairs a Harris image from a 1969 Civil Rights march in the lower Hill District with a Barack Obama “Pennsylvania for Change” rally captured in 2008. A female classmate chooses to show contrasting images of family: a formal portrait of a meticulously dressed soldier and his wife photographed by Harris in the 1940s and a 2009 image capturing two casually dressed, tattoo-covered parents lounging on the lawn of a city park with their two unkempt, smiling kids in tow. Infusing art across the curriculumOnce back in their home classrooms, the students’ trio of fifth-grade teachers—Michele Evans, Brent Rodgers, and Jeannette Adams— extend the field trip as part of a self-designed “Museum Art” course. With Croft’s help, they developed a three-dimensional collage project that the students worked on in January to display in time for Black History Month in February.

As part of the after-school program Picturing Me, students worked in pairs to compose self-portraits, making artistic decisions about lighting, pose, point of view, facial expression, and composition.

“We used the example of Martin Luther King Jr.,” explains Rodgers. “We asked ourselves how many times in a textbook have the kids looked at a picture of Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial? But then when we asked the students where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, only one or two students raised their hands. Having them associate his speech with that place and having them find a picture of it we hope will make it a more meaningful and memorable experience for them.” When the weather gets warmer, notes Evans, the trio will lead their students on a walking tour of historic Saxonburg, tasking them with documenting the everyday life of their neighborhood, just like Teenie Harris. “Because of their experience at the museum, we know when we give the kids the digital cameras it’s not going to be a snap and click free-for-all,” says Evans, who credits the museum’s earlier program integrating math and art, combined with the ongoing support of school principal Tom Tibbott, for inspiring their cross-disciplinary approach to teaching. “We know that our students are actually going to be looking at the sights and sounds in Saxonburg with the perspective of young photographers,” says Evans. “That’s the beauty of this program. It’s more than just a day trip. It’s a full learning experience.” “One of the overarching themes we explore with the students is the idea of choice. What choices can I make in this composition? What choices can I make in my life? ”

- J.G. Boccella, Museum educator and project manager for Picturing Me James Gouker, an art teacher at Pittsburgh Science and Technology Academy 6-12, was one of eight members of a teacher advisory team selected from dozens of applicants who helped the Museum of Art develop the Pittsburgh Past–Pittsburgh Present program that Evans raves about. Over five sessions last summer, the group studied reproductions of images selected for the two photography exhibitions and then brainstormed ways to approach them, developing classroom exercises for before and after students view the photographs at the museum. According to Gouker, who teaches digital photography and art through science, as well as video and graphic design, it was a win-win situation. “It gave us as teachers the opportunity to develop cross-curricular ideas based on something I would perceive as straight art,” he says. “Other teachers might take a different approach, historical or journalistic. As a group we were able to make it about more than any one of those things: localized history.” There’s a natural hook in photography, adds Gouker, because everyone with a cell phone practices it, yet it’s also in the museum. “Seeing photography in a museum is a different kind of experience,” he says. “It’s not a fine painting or a sculpture where students think, ‘I could never produce that.’ It’s inspiring, I hope. Especially these two exhibitions: The focus is on the students’ backyard and people who could be their aunts or uncles or the places that they see every day.” Back to the futureIn the after-school program, aimed at young people who have limited opportunity to visit museums or participate in arts experiences, the goal is to help kids discover how, over time, photographs become both personal and public history. Over seven weekly sessions, students practice looking more closely at artwork, as well as being more thoughtful about the ways they express themselves. One week, a theater instructor leads hands-on lessons about body language. Some 200 kids across five communities then put their newfound skills to use by taking self-portraits, creating collages, and interviewing each other on camera to create individual artist statements. “We talk about what a portrait is and teach the basic formal elements of photography,” says J.G. Boccella, project manager for Picturing Me. “One of the overarching themes we explore with the students is the idea of choice. What choices can I make in this composition? What choices can I make in my life? We explore the notion of how do I picture myself, how do I want others to see me—now but, also five and 50 years from now. We want to empower the kids to think about their future, to explore their personal goals and, along the way, build some confidence and expand their sense of what is possible.” Connecting with the success of people they could relate to was perhaps one of the most valuable lessons the students gained, says Kisha Fourguson, a fifth-grade teacher at Pittsburgh Lincoln and a supervisor at CLASP, an afterschool enrichment program by Calvary Episcopal Church for Pittsburgh Lincoln students. “Some of the kids had never been in a museum before, and in that way it was a new and valuable experience,” says Fourguson. “But then to be able to take the information they were learning and actually talk to a professional photographer and ask very specific questions about the choices he makes was incredibly beneficial.” When the students viewed the Teenie Harris exhibition, she says, some of them made the connection that Harris was a minority artist raised in a Pittsburgh neighborhood. “But they didn’t personally know the person who made the photographs,” she continues. “When they met Kenneth Neely, for them that was a turning point. Many of them said, ‘He’s just like me, he’s from my neighborhood.’ A lot of the places they are familiar with, Kenneth also is familiar with, either because he lived there or had taken pictures there, and that connection made a huge impression for them to think, ‘Now I can do this when I grow up.’” Neely himself grew up alongside the children of famous Pittsburgh sculptor Thad Mosley. “We’d go to their house and see a lot of his work,” Neely recalls. “That’s the thing. If you don’t see that there are minority artists in the city, you might think, ‘Do I even have an opportunity to do this?’ There are a lot of kids out there who are interested in the arts, but they just don’t get an opportunity to be around other artists or to ask artists questions. This program provides that important opportunity.”

|

|||||

Crossroads of Culture · Unpacking Andy · The Galloping Ghost of the East Coast · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Kota Yamazaki · Artistic License: For Nature's Sake · Science & Nature: Domino Effect · First Person: Dine and Discuss · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |