|

||||||||||||

Photography by Joshua Franzos |

Crossroads of Culture

Part of the mission of the new Center for World Cultures is connecting Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-class anthropology collections to today’s rapidly changing world. More than a century ago, in the Peruvian rainforest at the headwaters of the Amazon River, a hunter armed with little more than his own strength and prowess stalked one of the most deadly beasts within his ken: the jaguar. Once he had killed many of these predators, the hunter made a necklace from their teeth, proof of his own power and that of his respected enemy. Watching and listening to Deb Harding as she cradles the necklace today is a bit like stepping into a storybook. The teeth—some as long as a human forefinger and as thick as a human thumb—still exude the ferocity of their provenance. Harding conjures stories of the necklace’s bearer and his triumphs, imagining the object’s journey from the hunter’s hands or those of his descendents, to the white men who bartered for it in the 1880s, to Carnegie Museum of Natural History, which acquired the necklace in 1896, just a year after the museum opened its doors. That’s what’s imagined. What’s actually known of the necklace, other than that it hails from Peru, is very little. It’s one of the earliest acquired objects in the museum’s prized anthropology collection, which today boasts more than 700 necklaces from the Amazon basin alone.

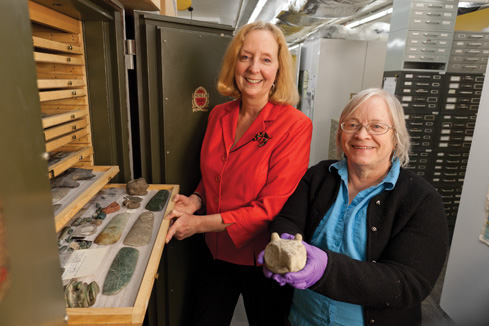

People from the Adena culture carved the above stone pipe smoked on only special occasions.

Excavated near Moundsville, West Virginia, this partially reconstructed tablet, once worn for decoration, dates to the Adena Culture, a community of prehistoric American Indians that lived in southern parts of Ohio and West Virginia some 3,000 years ago.

“I might’ve guessed that these teeth were from a pretty big cat, but I didn’t know they were jaguar, and I never thought they all could be,” says Harding, referring to the teeth’s variation in size. “But I took them to John Wible and Suzanne McLaren [curator and collections manager] in the section of mammals, and they confirmed that this necklace is made of all jaguar incisors.” Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s anthropology collections include 1.5 million archaeological objects, largely from western Pennsylvania, and 100,000 ethnographic and historical objects including significant holdings from both North and South America. Most of these treasures are fairly well documented with location and other key contextual information scientists need to help answer important questions about how cultures evolve. Artifacts from Ohio Valley’s Past Clockwise: Excavated near Moundsville, West Virginia, this partially reconstructed tablet, once worn for decoration, dates to the Adena culture, a community of prehistoric American Indians that lived in southern parts of Ohio and West Virginia some 3,000 years ago; People from this same group carved the above stone pipe smoked on only special occasions; The below rare “double pot,” estimated to be about 900 years old, is one of the many treasures unearthed at the Johnston Site in Indiana County, a location first excavated by a Carnegie scientist in the 1950s that continues to yield new knowledge about life in pre-colonial western Pennsylvania. But Carnegie Museum of Natural History is more than 115 years old: many of the oldest objects in the collection come from a more nascent stage of anthropology’s scientific development, yet are also among the most important, having been collected from cultures that have radically changed, or sites that are no longer accessible. “It’s so exciting when you learn something no one’s ever recorded before,” says Harding. “What I’m adding is basic data from which so many things can be interpreted: environmental use, trade, the introduction of exotic materials—it’s all there for us to find out.” Harding’s work is just one example of how scientists and science staff in the museum’s newly launched Center for World Cultures are working to add new value to the museum’s irreplaceable anthropology collections. One of the center’s most important goals, according to its director, Sandra Olsen, is finding ways to connect these collections to the greater scientific world. Olsen is a world-renowned archaeologist, best known for her research into the origins of the domestication of horses, which she has extensively researched in far-flung regions such as Mongolia and Kazakhstan. Olsen knows that by looking at individual objects and specific collections in new and different ways, the museum’s collections can become more scientifically relevant and accessible than ever—especially during this time of rapid global cultural change. “There are endangered cultures in the world just as there are endangered species,” says Olsen. “The fact that we’ve been around since 1895 means that this museum has collections from people who are no longer making those things, or who are making them in different ways. In order to see the whole process and understand the original traditions, we need to have those objects.”

Sandra Olsen, archaeologist and director of the Center for World Cultures, and Deb Harding, anthropologist and collections manager, cracked open a safe to show off some of the museum's most stunning jade figurines, many collected and purchased in Costa Rica by the section's first curator, Carl V. Hartman.

From Costa Rica to the Upper Ohio ValleyIn 1903, Carnegie Museum of Natural History appointed Carl V. Hartman as curator of ethnology and archaeology. Within two weeks, Hartman left Pittsburgh for Costa Rica to begin archaeological excavations and other activities researching that nation’s ancient cultures. What he brought back provided the foundation for the museum’s Costa Rican collection, today considered the best assembly of Costa Rican anthropological and archaeological materials outside of their native country. Hartman conducted the first scientific archaeological excavations there, bringing back numerous ethnographic collections and objects for the museum: stunning jade figurines and intact examples of turn-of-the-last-century ceramics that highlight a collection that is often as worthy of aesthetic appreciation as scientific study. Which, in some cases, is part of the problem: Those purchased objects arrived with no contextual knowledge. What are they made of? Where are they from, and from which period of the culture’s history?

“This is a dynamic, living entity; we’re not just storing collections like a great big closet full of potpourri.”

- Sandra Olsen, Archaeologist and Director of the Center for World Cultures

According to Alex Benitez, an archaeologist at George Mason University and project director of the Central American Ceramics Research Project at the Smithsonian Latino Center, it’s a problem common to older North and South American anthropological collections.

As part of his Smithsonian project, Benitez is looking at what can make those old collections—including the Hartman collections at Carnegie Museum of Natural History—newly useful to scientists. “These collections are only useful today if they’re relevant to the questions being asked today,” says Benitez. “You can continue to work in the field, to collect more objects. But there’s a stage at which we [scientists] want to re-engage these old collections, to ask new questions of them.” Benitez’s goal is to get the most up-to-date relevant data associated with collections like Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s, and to archive that information online so that scientists around the world can immediately tell where the materials they need to see are located. It’s a goal shared by the Pittsburgh museum’s newly created Center for World Cultures. “One of our major goals is to better house and better database these vast collections,” says Olsen. “We need to provide the space and the information that will allow researchers and educators to use these collections. This is a dynamic, living entity; we’re not just storing collections like a great big closet full of potpourri.” In 1903, the museum appointed Carl V. Hartman as its curator of ethnology and archaeology, and within two weeks of his appointment he set off for a seven-month excursion to Costa Rica, where he excavated and purchased scores of treasured artifacts. Among the most vast and unique collections of the anthropology holdings are archaeological objects from the Upper Ohio Valley. With more than a million and a half artifacts excavated in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio since the 1950s, it’s an irreplaceable wealth of archaeological information— a necessity for any scientist studying the culture of the early inhabitants of the region. But Olsen points out that this collection has yet to be systematically documented in a computer database: The only current records of those objects are still on paper. “We need those objects in a database and on the web so that researchers and educators can see the quantity and quality of that collection,” she notes, “and so they can imagine ways to use the information to answer their questions about the history and culture of this region.”

This Costa Rican grinding table, used to process corn and prepare other food, is called a metate. In the 20th century, young men made metates for courting.One archaeologist currently using the priceless collection is Sarah Neusius of Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Together with Beverly Chiarulli, she conducts the Late Prehistoric Project, a study of the sites of villages in western Pennsylvania that were active in the centuries before contact with Europeans (circa 1650). One site in particular, known as the Johnston Site in Indiana County, has yielded numerous artifacts and new knowledge about life in precolonial western Pennsylvania. It was archaeologist Don Dragoo of Carnegie Museum of Natural History who first dug at the Johnston site in the 1950s, and the artifacts from those excavations are accessible to the IUP scientists by way of Carnegie Museum’s collections. “In the 1950s, Dragoo didn’t have radiocarbon dating—now we can date artifacts,” explains Neusius. “We can use new methods to systematically collect small-scale plant and animal materials [from the excavation site] so we’re really adding to our understanding.” For example, one of Chiarulli’s graduatestudent researchers wrote her master’s thesis on modified bone implements found at Johnston, using both new excavations and the museum’s earlier collections from the site, combined with Olsen’s expertise on modified bone objects. “We’re really lucky to have access to Dr. Olsen and those collections,” says Neusius. “The ongoing relationship between IUP and the Carnegie Museum means a lot to this program.”

Reviving historyIt’s important to note that the knowledge held in old collections like those at Carnegie Museum of Natural History isn’t reserved for scientific research alone.

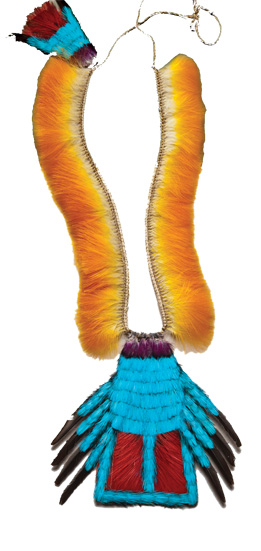

This headdress is worn by Shuar men in Eastern Ecudador. The bird, a Spangled Cotinga, is the source of the blue feathers in both the center of the headdress as well as the feathers for the necklace at top right.

At Oconaluftee Village, a living-history site replicating Cherokee life in the Southeast circa 1760, museum educators there discovered that the weaving of its craftspeople was decidedly not in the traditional Southeastern style of the period, known as the “oblique” style. When the Cherokee were removed from the Southeast to Oklahoma in the 1830s, that oblique style left with them. Harding knew of the long-dead tradition because she practiced it. “I never saw someone do it,” says Harding of the old finger-weaving style. “I taught myself to do it after studying pieces in museum collections. I studied the structure of archived pieces, and figured out that this is how you’d have to do it.” When the Cherokee were forced to Oklahoma, they lost not only their homeland, but some of the cultural practices that the homeland held. In their new home, their craftspeople learned other tribes’ finger-weaving techniques: the double-weave and singleweave as compared to their oblique and diamond-pattern forms. Upon returning to North Carolina generations later, the new techniques were handed down as Cherokee tradition. At the Cherokee’s invitation, Harding—having taught herself the old oblique tradition by studying pieces in collections in London, New York City, the Smithsonian, and at Carnegie Museum of Natural History—determined that she could help make things more historically accurate. “Here I am, the white girl, coming to tell them their stuff,” recalls Harding. “So the first thing I had to do was show that I had respect: for them, and for the people who came before them. Then I could start teaching people. By my third visit, I was teaching two classes a day and there were waiting lists.” “Deb’s research is really important because when we can add information to our database about the collections, it makes those collections infinitely more valuable to future researchers,” says Olsen. “What I’m adding is basic data from which so many things can be interpreted: environmental use, trade, the introduction of exotic materials—it’s all there for us to find out.”

- Deb Harding, Collections Manager for AnthropologyWith finger weaving, Harding has helped save a dying art. And her study of the collection’s Amazonian objects could wind up providing similar help to future scientists. “These Amazonian collections are from fairly recent peoples, but their culture is so endangered thanks to environmental change and commercial exploitation of the rainforest; they may not be around in 50 years,” says Olsen. “In the same way that the biologists feel this intense pressure to go out there and document what’s being lost to climate change and human population growth, we have that pressure, too, to document what’s being lost culturally,” she adds. “Our collections allow us to take the time we need to study those cultures, and for future archaeologists and anthropologists to come in and examine these pieces and say, ‘Ahh, now I see, that’s the way it used to be done.’”

The study of world cultures is on full display in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s exhibition halls devoted to the anthropological stories of cultures, past and present. Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians features more than 900 artifacts, including a wide selection of the museum’s nearly 300 objects from the Tlingit Indians of the Pacific Northwest collected in the late-19th and early-20th century. Among the clothing, bowls, baskets, and tools of these coastal peoples is a stunning multi-colored Raven Hat collected in 1904. It portrays a black and red raven carved from wood in totemic fashion— a taste, perhaps, of things to come.

In Polar World: Wyckoff Hall of Arctic Life, anthropological and biological sciences com bine to paint a portrait of Inuit life throughout the 100 years that Carnegie M useum of Natural History has visited the arctic. Paleontological studies of ancient arctic anim al life sit sideby- side with Inuit artworks both prehistoric and modern.

|

|||||||||||

Picturing Me · Unpacking Andy · The Galloping Ghost of the East Coast · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Kota Yamazaki · Artistic License: For Nature's Sake · Science & Nature: Domino Effect · First Person: Dine and Discuss · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |