|

||||||

|

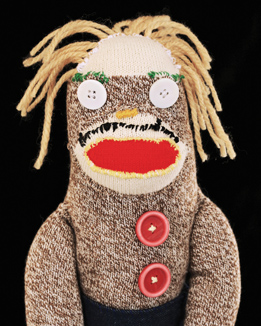

Above: Professional portraits of the students, paired with activities or objects they selected as motivators for their emotions, will be on view at The Warhol in an exhibition titled About Face, opening Feb. 4, 2012. Photography by Arne Svenson |

The art of reading a face

As part of an innovative new partnership with a local school, The Warhol is using Andy Warhol’s full bag of art-making tricks to help kids with autism develop face-reading skills.

It’s critique day, the teacher announces, a time to verbalize what works and doesn’t work in a classmate’s artwork. You can’t simply say you like or don’t like a collage, she explains, because it’s the why behind the opinion that’s important. “I can tell she’s feeling happy,” says 15-year-old Chris, pointing to a peer’s colorful portrait hanging from a clothesline in the front of the small classroom. Like all of the student projects, the woman’s face is pieced together from a mix of pictures clipped from magazines. “Her eyebrows are raised and she has a big smile,” he continues. “It’s a great big happy day for her.” “That’s great, Chris,” praises art teacher Lynda Abraham-Braff, “and good eye contact.” “Yeah, like that Steelers game,” pipes in John, clad in a black-and-gold Hines Ward jersey in the afterglow of a hometown team win squeaked out in a close contest the night before. “That was a happy day. But it was a nail-biter. I could tell by the look on my Dad’s face.” It’s an observation a little off task, maybe, but a victory all the same. The critique is designed as yet another means of reinforcing ways to recognize and interpret facial expressions, a skill most people take for granted but this group of 10 middle and high school students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) struggle with on a daily basis. They don’t instinctively recognize a friend’s scowl or a teacher’s stern stare as cues to tread lightly. When they do identify such an expression, it’s challenging for them to understand what the other person is feeling and how they should respond. So the fact that John gauged nonverbal emotions—unprompted and away from his directed classroom—is progress. This exercise is just one lesson in an arts-focused curriculum developed by educators at The Andy Warhol Museum in partnership with nationally acclaimed educator Abraham-Braff to teach facial cues to this moderate- to high-functioning group of students at Wesley Spectrum Highland School, a private school in the South Hills of Pittsburgh that serves students with learning and behavior issues. Now in its second year, the focus of the program is helping students interpret, as well as mirror, five simple emotions: happy, sad, angry, scared, and surprised. On this day, Chris married the two. “He had a big, bright smile on his face while he was talking, it was wonderful,” comments Jan Kustron, the school’s speech language pathologist recruited by Abraham-Braff as an in-class partner. But while promising, Kustron cautions that the students’ ability to read other people and express their own emotions appropriately is a gradual process. “You think you’ve made gains one day and the next day it’s lost,” she says. “There’s a need for continual repetition.”

Let’s Face It!Most people are considered face experts, says Jim Tanaka, a face researcher in the psychology department at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. “The brain reacts immediately to face-like stimuli relative to objects such as cars or chairs,” he explains. But that’s not the case for individuals with autism. This difference, he notes, seems to have its roots in an area of the brain called the furiform gyrus. In typically developed brains, this region is activated more by faces than other objects. But not so for people with autism; when looking at a face, the area of the brain that lights up for them is one typically associated with what’s called non-expert objects, suggesting that they view a face as just another object, not as anything special. As a result, they struggle with reading facial expressions, says Tanaka. His research indicates that kids with autism don’t disregard faces in general, but they tend not to look at eyes, which is consistent with the clinical description of the disorder. “All of this adds up to individuals with autism having difficulty reading and understanding what other people are thinking and feeling,” he says, “which of course impacts their social interactions.” To improve “face expertise” in children with ASD—now on average one in every 110 children—Tanaka developed the Let’s Face It! computer program, a collaborative project with the Yale Child Study Center funded by the National Institutes of Health. This series of computer games tasks kids with distinguishing faces from everyday objects, attaching labels to facial expressions, and interpreting the meaning of facial cues in a social context. On a visit to The Warhol two years ago, Tanaka shared the impact of the program, later published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, with museum educators. His research showed that when 42 children with autism played just 20 hours of Let’s Face It!, it created measurable improvement in their recognition abilities. (The program can be downloaded for free at http://web.uvic.ca/~letsface/letsfaceit.) “Our results are modest in that they’re not going to move a child off of the spectrum,” says Tanaka. “But the results can be replicated, which means this approach could work.” His drive to make that happen is what led him to The Warhol. “It’s the artists who know the most about faces and what goes into a face,” says Tanaka, who did his post-doctorate work at Carnegie Mellon University. “I was inspired by Andy Warhol’s approach that the observer becomes part of the art. I want our game user, a child, to become part of the game in order to make the game more meaningful, and to help make that leap from the computer screen into the real world.” During Tanaka’s visit to Andy’s museum, he found kindred spirits in Tresa Varner, The Warhol’s curator of education, and Abby Franzen-Sheehan, associate curator of education for interpretation and resources, who spoke with him about the museum’s regular Pop portrait workshops and how they use Warhol’s Screen Tests—a series of short, silent film portraits— to deconstruct the kinds of information one can glean from a face, and more. “They’ve long been thinking about the health benefits of the art of Andy Warhol in a very real-world way,” says Tanaka. “And they graciously, enthusiastically agreed to share their work.”

About Face Upon sharing tailored screen test and silk screening activities with kids at Tanaka’s annual summer “Face Camp” held at the University of Victoria—a kind of testing ground for prototype activities and a way for Tanaka and his staff to collect useful data while also serving kids—Varner instinctively thought of needs closer to home. “We understood that there is value in what we regularly offer in our workshops—talking about what is portraiture, interpreting it, dissecting the why and how it’s made to learn about yourself and others, to expand kids’ vocabulary,” says Varner. “We didn’t need to create a whole new curriculum for this project. It’s the same with our Alzheimer’s project. We just slow down, and using current research like Jim’s, focus on certain skill-building.”

“We want to teach the kids better self-awareness and understanding of nonverbal facial recognition skills, key tools in everyday problem solving.”

- Art teacher Lynda Abraham-BraffIn the fall of 2010, Varner and her team introduced specially developed art-making activities for an event at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh sponsored by the Pittsburgh chapter of Autism Now, an advocacy group. The response was positive. Then they pitched to Abraham-Braff, a longtime colleague, the idea of piloting a 30-session, semester-long curriculum with a group of her Wesley Spectrum Highland students. Abraham-Braff, who was recently named the 2011 Special Needs Art Educator of the Year by the National Art Education Association, selected a handful of students for the special elective and hit the ground running. “We want to teach the kids better self-awareness and understanding of nonverbal facial recognition skills, key tools in everyday problem solving,” she says. “These kids have a lot to offer.” To start, Leah Morelli, an artist and The Warhol’s school programs coordinator, introduced the students to—what else?—Warhol’s commissioned celebrity portraits. This led to the students creating their own silkscreened portraits. Among their favorite muses: Troy Polamalu, Taylor Swift, and Sidney Crosby. As part of the project, the group of nine boys and one girl, ages 10 to 15, explored 19th-century portraiture at the Frick Art and Historical Center, role-played with clay animation, tried their hand at ink-blot drawing in a face-building exercise, and even visited Warhol at his grave in Bethel Park. The team also introduced portrait photographer Arne Svenson’s popular book of sock monkeys as inspiration for the students breathing life into their own personified sock monkeys. Armed with thread and needle and a variety of colorful materials, students did their best to match their monkey’s facial expressions to its imagined personality and emotions. “They became personal and, in some cases, represent who the kids are as people,” says Morelli, noting that one student even gave his monkey a thin mustache to match his own.

By coincidence, Svenson, a New York City artist who has exhibited at The Warhol, was in Pittsburgh for another project and, at the invitation of Varner, stopped in to see the students’ creations. He was so taken with the kids that he ended up working alongside them to expand the project. “I literally got swept into their fever pitch of creativity,” says Svenson, who has a background in special education. “I wanted to take portraits of expressions made by the kids themselves. So often they’re shown a picture of someone else doing the expressing. An expression in a void means nothing, but an emotion that is reactive might strike a chord for the kid in the picture.” For each of the five emotions they’d been studying, the students were asked to think about something that evoked the emotion—a shark as scary or solving a math equation as happy—and then form a facial expression to match that feeling. Over a week, Svenson then photographed each student expressing all five emotions. “It wasn’t an easy task to get them to match their expression to the emotion; they struggle with identifying and mirroring emotion,” says Varner. “But it was a good learning exercise. And working with a New York artist, who was there specifically for them, gave them a huge boost in self confidence.” Produced as glossy keepsake booklets for the kids, the portraits—each paired with the object or activity selected by the students as motivators for their emotions—will be on view at The Warhol in an exhibition titled About Face, opening Feb. 4, 2012. This past September, The Warhol welcomed the group of students to the museum for a day filled with activities, including touring an exhibition all about superheroes, silkscreening, and storyboarding a simple comic using facial expressions as a guide. Towards the end of the visit, Morelli tells the students she has one last surprise, and together they walk to a display of eight framed black-and-white portraits by Eileen Lewis, a Pittsburgh artist who specializes in children’s portraits. Do you recognize anyone, she asks? No one speaks up, even as Morelli focuses in on a single image of a stylish and spirited little girl playing dress up and sporting a bold, near-seductive face. “That’s me when I was 7 years old,” she tells them. “I was dressed up like Madonna.” “What does her face tell you?” prompts Abraham-Braff as the students inch closer to check for a resemblance. “Anything?” “That she’s sassy!” exclaims John, his spot-on observation evoking appreciative laughter from his teachers. “Even I don’t know where I get some of this stuff,” he adds. “I don’t know either,” says Abraham-Braff, “but I like it.”

|

|||||

The ABCs of Discovery · Photographing My People · International Negotiations · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Linda Ortenzo · About Town: Game On · Artistic License: Contemporary Craft · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |