|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Photographing My People

Upon the first major retrospective of work by photojournalist Charles “Teenie” Harris, those with ties to the renowned storyteller share the impact of a single image. During the 1940s, Charles “Teenie” Harris earned about $35 a week as staff photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier, at the time the nation’s leading African American newspaper. When the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette offered him a higher-paying job, he declined. “I wouldn’t be able to photograph my people,” he explained to Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts for Carnegie Museum of Art, in a 1997 interview, a year before he died.

For nearly 40 years, Harris made images of change makers and celebrities including Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, Lena Horne, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jackie Robinson, and Dizzy Gillespie as they passed through his native Hill District, a hub of the national black community during the 1930s–1950s. But he stayed true to his passion for “my people” by capturing those members of the community that other photojournalists would overlook: a family in a tenement, men playing checkers outside a convenience store, and kids crowding an ice cream truck. Everyone—star to schoolboy—captured with the same care. Because his images—standouts not only for their content but for their expressiveness—reached a national audience through the Courier, Harris played a distinct role in how black Americans visualized themselves, locally and across the country. “Harris had great empathy with his subjects and a talent for storytelling,” says Lippincott. “His images transcend place.” Spanning the Great Depression to the final days of segregation, she notes, the Harris archive is recognized for being one of the most significant chronicles of mid-20th-century African American life. When Carnegie Museum of Art purchased Harris’ massive collection of some 80,000 negatives in 2001, most were unidentified. So the museum spent the past decade reaching out to the people who had been photographed by Harris or had roots in Pittsburgh’s black communities during Harris’ lifetime to help fill in the blanks. In October, Teenie Harris, Photographer: An American Story, the first major retrospective of work by this historic lensman, debuted at Carnegie Museum of Art. Large, themed photographic projections of nearly 1,000 of Harris’ greatest works accompanied by an original jazz soundtrack provide an unforgettable immersive experience. Visitors can also access some 63,000 additional digital images and an audio guide containing clips from oral histories collected by the museum. Starting next February, a version of the exhibition will travel to venues in Chicago, Atlanta, and Birmingham. According to longtime Pittsburgh Courier reporter and city editor George Barbour, Harris would be surprised at such a display of his work: “He’d say, ‘Who me? Little Teenie?’” “No one knows as much about Harris as the people he photographed,” says Kerin Shellenbarger, the collection’s archivist. So CARNEGIE magazine asked seven community members with ties to the legendary storyteller, some of them his past subjects, to perform the impossible task of choosing their favorite Teenie photograph and talking about what it means to them.

“This photo offers a glimpse of our family’s personal ‘Camelot.’”

- Charlene Foggie BarnettCharlene Foggie BarnettAs the daughter of Bishop Charles H. Foggie, who presided over the Wesley Center AME Zion Church in the Hill District for 24 years, Charlene Foggie Barnett was often in front of a camera, Teenie’s Speed Graphic in particular. “He always talked to me like a person—not a child, not a nuisance,” she says. A good thing, as she and her family were the subject of hundreds of photographs by the artist. About five years ago, Foggie Barnett attended an outreach event at the August Wilson Center for African American Culture seeking individuals to help identify the subjects of Harris’ photographs. In the images, Foggie Barnett immediately recognized a lot of familiar faces. Inspired by her love for Harris, she reached out to others who she knew could do the same. When Carnegie Museum of Art decided to start collecting oral histories to accompany the photographs, they looked no further than Foggie Barnett, who is now the collection’s oral history coordinator.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

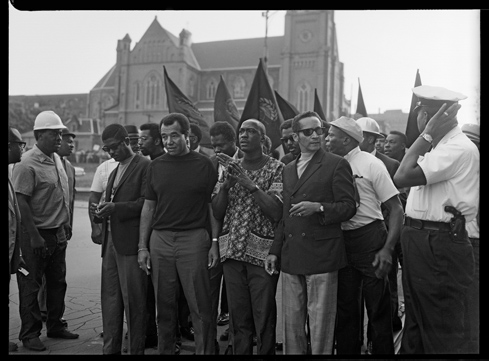

Charles “Teenie” Harris, “Black Monday” demonstration with Mike Desmond, Rev. Jimmy Joe Robinson, Nate Smith, and Byrd Brown in front, and others including Lloyd Bell, Dr. Norman Johnson, Aaron Mann, Louis Boykins, Vince “Roots” Wilson in light colored hat, police officer William “Mugsy” Moore, James “Swampman” Williams, and Matthew Moore in background, Freedom Corner, Lower Hill District, September 1969, Heinz Family Fund, Teenie Harris Archive © 2006 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

|

I chose this photo because it shows a good cross section of civil rights leaders and also because of the importance of the event. This demonstration marked a turning point in the civil rights struggle. In 1963, when I marched on Washington with Dr. King, the civil rights movement was aligned with organized labor. Here, we had to march against labor unions. At this time, the construction unions in Pittsburgh were less than 2 percent African Americans and this demonstration was trying to open up more construction jobs for blacks.

One of the results of this demonstration was that the city could no longer tolerate unions that were segregated.

At this point I wasn’t a leader. I’d just gotten back from the south and was just there to march. The significance didn’t occur to me at the time. I only realized it much later. When you’re right there in the moment, you don’t know you’re making history.

Ralph Proctor

As an historian and a member of the six-person advisory committee for the Teenie Harris Archive, Ralph Proctor is well-positioned to select a photograph for its historical significance. As it turns out, of the tens of thousands of images taken by Harris, the chair of ethnic and diversity studies at the Community College of Allegheny County chose an image of the same event as Sala Udin, speaking to its lasting legacy. But Proctor also sees with the eye of a photographer, choosing this image not only for its historical importance, but because of its “exemplary” composition.

|

Charles “Teenie” Harris, “Black Monday” demonstration on behalf of Black Construction Coalition with protesters marching down Centre Avenue near Civic Arena and Chatham Center, Lower Hill District, September 1969, Heinz Family Fund, Teenie Harris Archive © 2006 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

|

One’s eye is drawn to the long line of marchers as they disappear beyond the horizon. While the exposure may not be “perfect,” the photograph says something of significance. It moves the human spirit! The angle gives greater impact because it emphasizes the magnitude of the event, as well as the impressive number of people gathered.

As a Pittsburgh-born historian, I can relate that this photo-graph represents the height of the power of the Pittsburgh movement. At this point, Byrd Brown, president of the Pittsburgh NAACP, could put out a call and gather thousands of people, black and white, to protest racial discrimination. This was one of the largest demonstrations of the era. As a participant, my chest swells with pride because I know many of the people in this long, impressive line. Not only were there the leaders of the movement; there were also ordinary people who joined to make their statement about racism and inequality in Pittsburgh. They may have been ordinary when they joined the march, but by the time they reached Downtown, they were heroes—warriors in a movement that changed Pittsburgh. We may never know all their names, but this photograph is a moving, lasting tribute to the unsung, unknown heroes of the Pittsburgh civil rights movement. Say “Amen,” Brothers and Sisters, say “Amen.”

- Harry clark

Harry Clark

In 1967, a nervous Harry Clark posed with his new bride, Barbara Lee Alston Clark, by their wedding cake. One of his wife’s relatives was tasked with taking their photograph. “Relax, you’ve married a good woman,” the photographer said, loosening up Clark so he would crack a smile. That photographer was Teenie Harris.

Clark, a native of the North Hills, is a musician and music teacher. He served in the Pittsburgh Public Schools for 30 years and founded the Pittsburgh High School for the Creative and Performing Arts, now CAPA 6-12. He was the principal there until his retirement in 1993. Retirement hardly slowed him down. He went on to be the national director of academic relations at Full Sail Center for the Recording Arts in Orlando, Florida, and for more than 14 years, he’s served as an advisor for the African American Jazz Preservation Society of Pittsburgh.

His favorite photograph by Harris is, of course, his wedding photo, but a close second is this group shot of the Westinghouse High School jazz ensemble taken in 1957.

|

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Westinghouse High School jazz ensemble members, from left: Nelson Harrison, Janson Kelly, Paquita Sharp, and two unknown young men, in Carnegie Music Hall for All-City high school orchestra concert, April 1957, Heinz Family Fund, Teenie Harris Archive © 2006 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

|

I was one of five blacks—coloreds we called them back then—who attended West View [High School] and was the first African American drum major in the school district. In 1957, that was huge, and our band director took a lot of heat. When I went to a conference for high school musicians in western Pennsylvania, it was one of the few occasions I saw musicians who looked like me during high school. Now you have to understand what that meant; I didn’t even have a black teacher until I got my doctorate. At this conference, I saw this black trombonist and he really strutted his stuff. So I also strutted my stuff. That trombonist was Nelson Harrison, who’s in this picture on the left. He went on to play in a lot of groups including with Count Basie. We also became friends and to this day when we run into each other we reminisce about how we were checking each other out. I’ll never forget that conference. I discovered a whole outside world.

George Barboue

Harris didn’t exactly welcome George Barbour with open arms when the young photojournalist applied to the Courier in 1953. In fact, Harris complained to the Newspaper Guild, saying he was the only photographer at the Courier. So Barbour opted to be a reporter instead and never regretted it.

The two quickly smoothed things over and became close friends and partners, teaming up for stories and on the basketball court at the YMCA across from the newsweekly. After Barbour left the paper in 1964 to become the first African American hired by KDKA and Westinghouse Broadcasting, he remained friends with Harris, who lived just a few blocks away. When Barbour’s wife, Gloria, went into labor with the couple’s second child, it was the Harrises who babysat their son.

“Teenie had a nose for news,” Barbour recalls, explaining that his colleague didn’t rely on reporters to tell him what pictures to get. Although Harris snapped a lot of unfolding action, Barbour chose this photograph of the Courier offices because of the fond memories it evokes.

|

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Office with women and men working at desks, and sign in background reading “Editorial Dept.,” at Pittsburgh Courier newspaper, c. 1950–1965, Heinz Family Fund, Teenie Harris Archive © 2006 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

|

This photo takes me back to the good old days! On the right is the local desk, that’s where I sat. And in the back is the national desk. Usually there was a lot of activity. On this day we must have been all out covering a story.

I was proud to be at the Courier because we had a lot of prestige. We were looked on as the integrator, the battler for race. We weren’t just supposed to report on the news, we were supposed to make the news. If there was a report about discrimination, we were supposed to get involved. When we found out they were discriminating against blacks at the swimming pools, restaurants, and theaters in Canonsburg, we went out there. We didn’t just report, we also helped establish a branch of the NAACP in Washington County.

Teenie was a quiet man, but he had spunk in him! Teenie’s contribution to the advancement of blacks in this city was tremendous—he never talked about it that way—but it was just tremendous.

Kerin Shellenbarger

Since 2002, Kerin Shellenbarger has spent her days researching and cataloging the 80,000 negatives in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Teenie Harris Archive. “Cataloging is really tedious,” she says. “But somehow I haven’t gotten tired of this collection. The images are really compelling.” Because Harris photographed almost exclusively in and around Pittsburgh, Shellenbarger started to recognize the same people appearing over time in the negatives. “I can see people growing up, gathering friends, getting married and sometimes remarried, and having children,” she explains. “There’s a rich interconnectivity of people’s lives in the photographs.”

Interconnectivity between a national celebrity and Harris is illustrated in Shellenbarger’s tale of a 1938 shot of Duke Ellington, William “Woogie” Harris, and others watching a basketball game.

|

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Bill Snyder, Woodson Norvell, Duke Ellington, and William “Woogie” Harris

|

We recognized Duke Ellington and Woogie, Teenie’s brother, when we cataloged this negative in 2005. We assumed they were at a boxing match since Woogie managed boxers at that time. We were wrong.

Six years later, I came across the image in New York Public Library’s collection of Flash Newspicture Magazine. It appeared in the February 28, 1938, issue with the cutline: “The flash bulb proved momentarily more interesting to Duke than the basketball game between The Rens and The Pittsburgh Pirates at Duquesne University. Left to right are Bill Snyder, Woodson Norvell, Duke Ellington and Woogie Harris.” At that point, Teenie had just begun his life in photography—he had recently purchased his beloved 4x5 Speed Graphic camera, freelanced steadily for Flash, and was about to publish some uncredited images in the Pittsburgh Courier. He also played on and managed a basketball team he named “Flash.”

With the new facts, I searched for additional information in the Courier. There I discovered that Ellington was in town that week to perform at the Stanley Theatre. Woodson Norvell, who was described in 1939 as “The Hill’s dapper mystery man who knows all and sees aplenty,” owned the Norvell Hotel where Ellington stayed on an earlier trip to the city. Woogie, a numbers baron who earned the elegant title of “digitarian” by longtime Courier reporter Frank Bolden, was close with fellow sportsman Bill Snyder, and both were named top “jive-men” in 1939.

So, on Thursday, February 10, 1938, 1,500 fans including Ellington and his sporting friends came to watch the New York Renaissance defeat the Pirates. Two days later, Teenie’s Flash team lost to the Rens at the Centre Avenue YMCA, 53–30.

- Christian Harris

Christian Harris

Not everyone can say their great-granddad is in a museum,” says 15-year-old Christian Harris, noting his pride in being Teenie Harris’ great-grandson. A sophomore at Penn Hills High School, the young Harris enjoys football, wrestling, and baseball. He also loves—what else?—taking pictures. When he started taking photographs at about the age of 10, his grandfather Lionel, Teenie’s third son, decided to tell him about his famous relative. “The more I knew, the more I wanted to know,” he explains, adding that photography is simply in his blood. He particularly likes taking images of nature. “If I see a good sky, I’ll take a picture of it,” says Harris. The teenager never had the opportunity to meet his famous great-grandfather, whom he affectionately calls “Dad,” but says he loves him just the same. Given Christian’s love of sports, it’s no surprise he chose this 1955 photograph of men playing a pickup game outside a steel mill.

|

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Sandlot baseball players outside steel mill, 1955, Heinz Family Fund, Teenie Harris Archive © 2006 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

|

I like it because, even though it wasn’t a major league game, my great-granddad still took a picture of it. Dad would take photos of pickup games, minor league games, Negro League games; it didn’t matter to him what kind of game it was, if he wanted to take a picture he would go ahead and snap. It shows his love of taking pictures. Other photographers might have said, “Oh this is just a pickup game. It’s not important.” But not Dad. When he wanted to take a picture, he did just that. The picture also shows his love for baseball and sports. In general Dad loved to play baseball—absolutely loved it! That’s one of the reasons I’m into baseball today.

The ABCs of Discovery · International Negotiations · The Art of Reading a Face · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Linda Ortenzo · About Town: Game On · Artistic License: Contemporary Craft · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |