Spring 2010

|

||

|

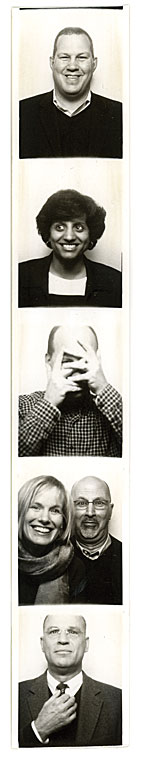

photo: renee rosenseelThey met at The Warhol one January evening, took their mug shots in the basement photo booth, then swapped ideas about what the museum might do next. Far right, top to bottom: Randy Dearth, Priya Narasimhan, Chris Potter, Jane Werner and Saleem Ghubril, and City Councilman Bruce Kraus.

|

The Next 15 The Next 15As The Warhol gets set to officially celebrate its first 15 years, Director Tom Sokolowski gathers an eclectic group of Pittsburghers to talk about the future. By Cristina Rouvalis The Andy Warhol Museum is 15, and like most teenagers, it’s both inspiring and infuriating, a hip newcomer and a nose-thumbing rebel.The Warhol has always been more than just a place to hang oversized Campbell’s soup cans and silkscreens of Jackie and Liz. Defying skeptics, the museum has found a following in Pittsburgh by morphing into an edgy performance art center, a Friday night hangout, a place to see street art, or confront horrifying photos of lynchings. The museum channels the spirit of The Factory, Warhol’s New York art studios where painting, film, music, and celebrity melded into something startling and fresh. The museum today is ever-changing, a place that dares people to look at contemporary issues creatively through the life and Pop Art of its namesake. But what will the teen be like when it grows up? Okay, so maybe The Warhol will never grow up if it stays true to the vision of the eternally young Warhol. So let’s rephrase: How can the museum reinvent itself over the next 15 years so that it stays young and provocative? To brainstorm about the museum’s Warholian future, Warhol Director Tom Sokolowski assembled a panel of Pittsburgh thinkers from diverse fields. His roundtable picks included Priya Narasimhan, computer engineering professor at Carnegie Mellon University and president of YinzCam, a young start-up that developed a cool way for sports fans to view unique camera-angle footage from their seats; Saleem Ghubril, executive director of The Pittsburgh Promise; Chris Potter, editor of City Paper; Jane Werner, executive director of the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, who has partnered with Tom Sokolowski on, among other things, the reopening of the North Side’s New Hazlett Theater; Randy Dearth, president and CEO of LANXESS Corporation and chairman of The Warhol board; and City Councilman Bruce Kraus. “These are people who have taken their venues and views and have done things that stretch the box and gone outside of it. In their own ways, they are all fearless,” says Sokolowski. “They are not as loud and vulgar and pushy as I am, but they are fearless in the sense of breaking the rules for a good product.” Sokolowski opened with this challenge: “How can a museum be not only a zone of tranquility but perhaps a zone of aggression?” He also urged panelists to suggest ways to attract more young people—whether they are college students who rarely venture out of Oakland, suburban high school students wary of the city, or youth who have not been exposed to contemporary art, whatever the reason. “Be audacious,” Sokolowski advised. “Be rapacious. I love that word!” Cyber WarholPriya Narasimhan: At CMU and Pitt, we have all these students who would love to get their hands on doing something interesting here, and transporting The Warhol experience outside The Warhol doors. We could do a mobile app for people to use before they come here. People could download it and explore it on their own. Take The Warhol tour of all the places he lived, breathed, worked in. Or you could play six degrees of Warhol—perhaps easier than you could play six degrees of Kevin Bacon. ‘What’s your Warhol number?’ If you could make it into a game, you could engage kids. Randy Dearth: We have this vast treasure. How do we take it out to the larger cyber world? There is a dig in Argentina. How cool would it be every day at a certain time to let kids go online and interact with that archaeologist? Same with our Warhol Time Capsules (The museum is opening and archiving the 610 Time Capsules Warhol compiled in his life). We could set up a camera that would be running 24/7 and take it out to the world and say, ‘We are opening a Time Capsule. Come to our website.’ Chris Potter: Let’s put artwork out into the world, outside of the museum, in a way that leaves breadcrumbs for people to trail their way back to the museum. The Warhol’s reputation is that its youth programming, more than any other art or cultural institution, is the best in town. To whatever extent that can be built on, maybe an artist in residency, I don’t know. But I think it’s a way to expand and connect with the community. Tom Sokolowski: Could we have a journalist in residency? Could it be an advertising person in residence? Chris Potter: No. You want it to have integrity, right? (laughing) Tom Sokolowski: Oh come on. We are all branded to one degree or another. How we dress. Where we go to church. Where we go to school. Our political affiliation. Chris Potter: That’s true. Also, I am surprised that The Warhol website is not stronger. I always found it locked in 1998. Tom Sokolowski: That is about to change. Fifteen minutes, and more The new Warhol website, which will debut later this year, will give visitors their 15 minutes of fame through various interactive features. The user-generated component of Warhol.org, “fifteen” opens with this quote: “A lot of people thought it was me everyone at The Factory was hanging around, that I was some kind of big attraction that everyone came to see, but that’s absolutely backward: it was me who was hanging around everyone else. I just paid the rent, and the crowds came simply because the door was open. People weren’t particularly interested in seeing me, they were interested in seeing each other. They came to see who came.” The new Warhol website, which will debut later this year, will give visitors their 15 minutes of fame through various interactive features. The user-generated component of Warhol.org, “fifteen” opens with this quote: “A lot of people thought it was me everyone at The Factory was hanging around, that I was some kind of big attraction that everyone came to see, but that’s absolutely backward: it was me who was hanging around everyone else. I just paid the rent, and the crowds came simply because the door was open. People weren’t particularly interested in seeing me, they were interested in seeing each other. They came to see who came.” Likewise, people who visit “fifteen” will be able to see who else is hanging out online. People will be able to upload their own artwork to the site, create an artist profile, and comment on other artists’ work. An LCD screen on the second floor of the museum will flash each piece of artwork for 15 seconds (sorry, not 15 minutes). Another link will invite curators to come up with a theme and compile online exhibitions. The best work will be showcased in an online “Stars” gallery. “The idea is that fabulous artists will be selected by our curator for the star section,” says Tresa Varner, curator of education and interpretation at The Warhol. And virtual visitors will be able to upload items to a massive online time capsule. As democratic as this sounds, the Velvet Rope link will be something altogether different: an exclusive, invitation-only part of the site. “It will be like being in the back room at Max’s Kansas City, where Warhol hung out,” Varner says. “There will be all these cool, creative people—it’s a meet and greet and a way to share creative ideas.” Throwing bombs, or notJane Werner: As much as you can do virtual stuff, there is something about going to an institution and walking through the galleries. It’s important to do. The thing about The Warhol is it is a platform where people can feel differently. There are very few civic places where you can bring in topics like lynchings. (In 2001, the museum hosted Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America.) Where else in the city could this happen? I think the problem is that not more people take advantage of The Warhol. I printed out your statistics: 100,000 visitors a year. Tom Sokolowski: You (the Children’s Museum) are two and a half times that. Yes, the Warhol is 100,000 visitors a year. But in the last 12 years, we have served nine million people in all the shows we sent from Rome to Paris and Kazakhstan of all places. So, here at the museum, how aggressive can we be about things we believe in? Let us say kids come in and want us to do something that deals with an aspect of sexuality or drugs or illegality, how aggressive should we be? We always think these institutions are so wonderful, so neutral, never a fart. Chris Potter: You are like the bomb thrower of the Three Rivers. Saleem Ghubril: You can be too out there in the right or the left. I caution you and The Warhol against trying so hard to be avant garde that you stop being relevant and meaningful. With Without Sanctuary, we weren’t trying to make a point. We put a mirror in front of those viewing. We didn’t have to say, ‘Bad, bad, bad people.’ The mirror did the talking without us trying so hard. Chris Potter: You could bring in some hot-button issues. Maybe a one-year anniversary of G-20 in Pittsburgh. The issue I find amazing is immigration—the hot-button issue of the immigration of the Latino community. It does exist here, but we have less than almost anywhere else. And still it’s such a hot-button issue. We could pay attention to Latinos in this vaulted cultural institution. Saleem Ghubril: I am an immigrant born in Beirut. I am a Christian pastor. What if you highlight modern-day immigrants in Pittsburgh who are not costing jobs and on welfare, and who are not stereotypically running 7-Elevens and driving taxi cabs? Tom Sokolowski: If you go to The Strip on Sunday, you see Somali women. They are these amazing people you never see any other place in the city. What if we look at the Pittsburgh not represented by the Nationality Rooms? The faceless Pittsburghers or something along those lines? Maybe every Sunday night we could have a potluck dinner here? It might be an interesting way of getting international people—those Somali women—or disenfranchised students. Priya Narasimhan: Maybe look at the faces of Pittsburgh cab drivers. Tell their stories. A lot of them have gone away and come back. It’s hard to be a taxi driver. So why are they here? I have another suggestion. It is sort of gimmicky. Pittsburgh is a sports town. You have to exploit that at the end of the day. Tom Sokolowski: There is an exhibition in Ohio, a show on masculinity and sports and what that means. What does wrestling really mean? In all seriousness, is it a bad thing? Does it mean all athletes are gay? The bonding that men have is a form of affection. Our society, then, becomes more aware of the ambiguity. The Coffee Shop MuseumTom Sokolowski: What does Pittsburgh need that we perhaps, in our weird, malevolent, baroque way could help? Bruce Kraus: Public space and public art are incredibly important for a sense of community, so that everyone comes together in common places and interacts. Randy Dearth: What about literally taking the museum to the South Side? There are empty storefronts all over the city. Go in and open a coffee shop and bring some books we can sell. We can have speakers come in. Maybe go to Carson Street for six months, rent a storefront, then we move to Bloomfield. Jane Werner: Arts organizations exist in a neighborhood. They can provide fertile ground for change. You go into Oakland, where college students are, and make it safer. The Warhol is one of our (the Children’s Museum’s) best collaborators. We have two different perspectives. We push Tom to see how kids see things. Tom pushes us to be more innovative. The Warhol always makes me think differently about museums. Save the Date: On May 15, The Warhol will celebrate its 15-year anniversary the Andy way, with a big, flashy affair. Stay tuned for more details.Making more room for AndyFor John Soh, the classroom assignment was both thrilling and daunting: design an annex for The Andy Warhol Museum.Not only did the Carnegie Mellon University architecture student want to create something provocative and Warhol-worthy, he had to deal with the more concrete challenge of putting four very different elements into the building: a flexible theater/performance space, a restaurant, office space, and apartments—in seven stories or less. The new building would be across the street from The Warhol where the former Rosa Villa restaurant stands.  Soh, 23, developed a design of digging out the basement and building an airy three-story theater from the bottom up (above). “The theater is prominent,” he notes. “You walk into the lobby and you see a big space in front of you, even if there is no performance currently happening.” Getting Carnegie Mellon students involved in imagining a future expansion of The Andy Warhol Museum’s space was the brainchild of Mick McNutt, CMU architecture professor and an architect with EDGE Studio in Friendship, the firm that designed The Warhol’s new admissions desk. Of all the student concepts, Warhol Director Tom Sokolowski was most drawn to Soh’s. “He took this broad rectangular line, and then took this chunk out of the building and dealt with it theatrically. It’s an exciting element.” At this point, the designs of Soh and his 12 classmates are an intellectual exercise that helped them get real-life experience dealing with real-world constraints and a living, breathing client. The Warhol plans to use the ideas as a jumping-off point to begin thinking about a possible expansion. Carnegie Museums acquired the Rosa Villa building in 2006, and The Warhol sometimes uses it for non-art-related storage. “There is no Campbell’s soup can over there,” jokes Ben Harrison, the museum’s associate curator for performance and liaison for the CMU class project. The Warhol, says Harrison, hopes to eventually build an annex that would include a nontraditional theater space for up to 300 people in an open, standing-room configuration, allowing for more room to mingle. The museum’s current theater is too small and constraining for larger performances. “Warhol was the pioneer of multi-sensory rock shows, that were ear-splittingly loud and designed to unsettle,” Harrison says. “Even today, for many young, independent bands, Warhol is still very much on their radar. They often consider it a coup to perform here.” An expansion could also free up gallery space in the main museum since offices could be relocated across the street. The new building could also house a restaurant and apartments for artists in residency. Says Sokolowski, “It would be great if in five years, we found the funding, and we found John and said, ‘Now that you are a certified architect, would you want to work on the building?’” |

|

Also in this issue:

I Just Want to Watch · Regenerative Medicine: A Growing Future · Run, bounce, spin, climb— and learn! · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Heather White · Science & Nature: Our Super-sized World · Artistic License · About Town: Asking Andy · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |