Spring 2010

|

||

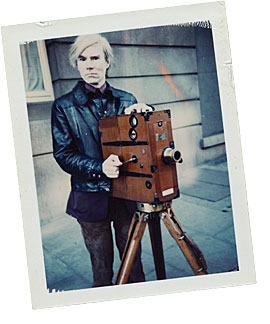

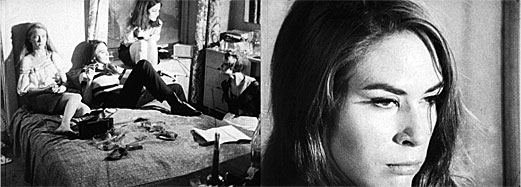

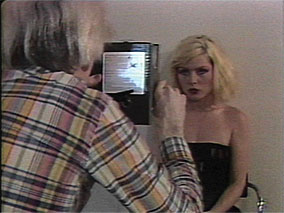

Above: Based on the life and death of actress Lupe Velez, the 1965 film Lupe was the last official film Edie Sedgwick made with Andy Warhol.Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait with Movie Camera, 1971, The Andy Warhol Museum, Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Fundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © AWF |

I Just Want to Watch

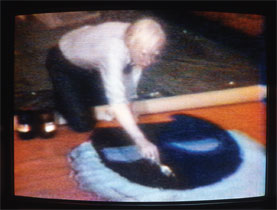

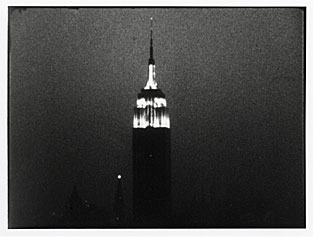

The Warhol unveils an expansive installation that provides a new angle By Justin Hopper In the early 1970s, 20-something Vincent Fremont enjoyed a rather strange line of employment. He would frequently set up the Sony Portapak video camera that Andy Warhol taught him how to use, capturing the peculiar whatever unfolding inside Warhol’s infamous Manhattan studios, The Factory. And every now and then, the result would be instant history.“By the 1970s, Andy didn’t like to be filmed working in the studio anymore,” says Fremont, who in a way still works for the Pop artist as the sales agent for The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. “But once, I set up in The Factory and videotaped him painting. That process—him working in the studio—hopefully it helps clear up people’s confusion about Andy as a painter. He said he wanted to be a machine, but that was a conceptual part of his 1960s work; his painting is all about the human touch. I was aware that I was documenting something historic, but so often you had to push that aside to take care of the day-to-day.” Fremont not only had the opportunity to document such remarkable moments, but to often be part of them. Besides working on a slew of video projects throughout the 1970s, Fremont eventually became the producer of Warhol’s ’80s television programs, including Andy Warhol’s T.V. As Fremont confirms, Warhol was obsessed with new artistic media and documenting his life and world: From Polaroids to his ever-present audio tape recorder; and, from the first time he got his own movie camera in 1963 until his death in 1987, film and video. In that period, Warhol built a massive body of work, including both what he shot and what was shot in his name by colleagues such as Fremont. For decades, much of this work had been relegated to the background by mediators of Warhol’s artistic output. But in the 23 years since his death, curators, critics, and audiences alike have taken a new and passionate interest in Warhol’s film and video work. And now, The Andy Warhol Museum is set to launch a multi-year, mass-scale installation that will represent the most extensive broad-based look at that work: An entire floor of the museum dedicated to screening Warhol’s films, television shows, and stacks of previously unscreened experimental and documentary films and videotapes. With the March 28 debut of I Just Want to Watch: Warhol’s Film, Video, and Television, Geralyn Huxley and Greg Pierce, the museum’s curator and assistant curator of film and video, hope to provide a new angle on Warhol’s relentless experimentalism, work ethic, and, perhaps most of all, his boundless curiosity about the people who inhabited the world around him. Warhol’s extracurricular activities Behind a door secreted away in a darkened screening room on the sixth floor of The Warhol is an office shared by Huxley and Pierce that’s completely inundated with Warhol’s films and videos. Books of Warhol scholarship tumble out of too-full shelves, and reels of film—carefully wrapped and wrapped again—sit waiting to be shipped out to anxiously awaiting galleries and theaters. While often ignored during Warhol’s lifetime, over the past decade-plus Pierce confirms that the artist’s films and videos have indeed become more and more prevalent aspects of the artist’s oeuvre. And there’s a fairly simple reason why: People are starting to actually see them. Behind a door secreted away in a darkened screening room on the sixth floor of The Warhol is an office shared by Huxley and Pierce that’s completely inundated with Warhol’s films and videos. Books of Warhol scholarship tumble out of too-full shelves, and reels of film—carefully wrapped and wrapped again—sit waiting to be shipped out to anxiously awaiting galleries and theaters. While often ignored during Warhol’s lifetime, over the past decade-plus Pierce confirms that the artist’s films and videos have indeed become more and more prevalent aspects of the artist’s oeuvre. And there’s a fairly simple reason why: People are starting to actually see them. “He was, first and foremost, an artist. All the ‘extracurricular’ work that he was doing—that’s the key word, because people didn’t think it was important, but it was—it was all extensions of his art.”- Vincent FremontPHOTO: JOSHUA FRANZOS “They were out of the limelight for 15 or 20 years or more. Nowadays, any film that’s been preserved can be seen and not just in galleries, they’ve been shown in theaters, too. On the other hand, the TV shows were on New York City cable. So unless you saw them then, that’s it. And since it’s Warhol, the hunger for this stuff is intense.” “They were out of the limelight for 15 or 20 years or more. Nowadays, any film that’s been preserved can be seen and not just in galleries, they’ve been shown in theaters, too. On the other hand, the TV shows were on New York City cable. So unless you saw them then, that’s it. And since it’s Warhol, the hunger for this stuff is intense.”Warhol’s love for the movies is well documented: From his early days collecting movie-star images in his scrapbook, and walking to see films at the now-defunct Strand and Schenley Theaters in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, to his famous paintings of movie stars such as Marilyn Monroe later in life. With the arrival of that first 16mm camera in 1963, Warhol began to see the world around him through a lens-like eye. He was one of the first to acquire a consumer-grade video camera, a Norelco prototype in 1965, and never ceased upgrading his equipment. Throughout the ’60s, he stood behind that equipment, creating such famous films as Sleep, Camp, and his famed The Chelsea Girls, which featured many of Warhol’s superstars as if they lived in New York’s Hotel Chelsea. After the failed shooting attempt on his life, says Huxley, “Warhol never fully returned to his role directly behind the camera.” Paul Morrissey took over most of the directing on Warhol’s films, while Michael Netter and, soon afterwards, Vincent Fremont began shooting the video. Becoming a film and video producer rather than the director was a blossoming of the factory-like concept of Warhol’s art making. ALL IMAGES © THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM The Chelsea Girls featuring Angelina “Pepper” Davis, Mary Woronov, Susan Bottomly, and Ingrid Superstar, with a close-up of Woronov“He was, first and foremost, an artist,” says Fremont. “All the ‘extracurricular’ work that he was doing—that’s the key word, because people didn’t think it was important, but it was—it was all extensions of his art. He didn’t do what might be considered ‘art videos.’ For example, he really wanted to do a television show. So we were developing ideas. And if you discussed with Andy what you wanted to do, and what he wanted, and if he trusted you, he would give you full support to just go off and do it.”In a 1974 Factory Diary, Warhol paints a drag queen Among the videos that Fremont wound up filming were two bodies of work that even many Warhol aficionados have never seen: Warhol’s constant taping of the goings-on at The Factory, now referred to as Factory Diaries; and a series of soap operas-in-development, experiments in low-budget television that Warhol and Fremont hoped would one day become broadcast-TV dramas. Alongside the 42 episodes of New York-cable shows Fashion and Andy Warhol’s T.V. and the series shown on MTV, Andy Warhol’s 15 Minutes, all produced by Warhol, the more than 1,500 tapes of Diaries and other experiments that The Warhol holds in its archives create an opus impressive in their mere quantity. Add to that the continuing influence of Warhol’s documentary-style drama—the blueprint for reality TV—and I Just Want to Watch becomes a touchstone for contemporary art and popular culture as we know it. Among the videos that Fremont wound up filming were two bodies of work that even many Warhol aficionados have never seen: Warhol’s constant taping of the goings-on at The Factory, now referred to as Factory Diaries; and a series of soap operas-in-development, experiments in low-budget television that Warhol and Fremont hoped would one day become broadcast-TV dramas. Alongside the 42 episodes of New York-cable shows Fashion and Andy Warhol’s T.V. and the series shown on MTV, Andy Warhol’s 15 Minutes, all produced by Warhol, the more than 1,500 tapes of Diaries and other experiments that The Warhol holds in its archives create an opus impressive in their mere quantity. Add to that the continuing influence of Warhol’s documentary-style drama—the blueprint for reality TV—and I Just Want to Watch becomes a touchstone for contemporary art and popular culture as we know it. Warhol’s 1964 silent, black-and-white film, Empire,

|

|

Also in this issue:

The Next 15 · Regenerative Medicine: A Growing Future · Run, bounce, spin, climb— and learn! · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Heather White · Science & Nature: Our Super-sized World · Artistic License · About Town: Asking Andy · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |

More than just

More than just  In the 1970s and ’80s, that negative point of view wasn’t reserved for the cultural mainstream. According to Crimp, Warhol’s films weren’t necessarily seen as a part of Warhol’s serious artwork during his lifetime. “There tended to be an orthodoxy in Warhol scholarship, right through to the 1988 MoMA retrospective that followed Warhol’s death—that the important work by Warhol was the classic Pop painting from 1962 to ’66,” says Crimp. “That’s been broken down as people have seen the other work and been able to form a different attitude about it.”

In the 1970s and ’80s, that negative point of view wasn’t reserved for the cultural mainstream. According to Crimp, Warhol’s films weren’t necessarily seen as a part of Warhol’s serious artwork during his lifetime. “There tended to be an orthodoxy in Warhol scholarship, right through to the 1988 MoMA retrospective that followed Warhol’s death—that the important work by Warhol was the classic Pop painting from 1962 to ’66,” says Crimp. “That’s been broken down as people have seen the other work and been able to form a different attitude about it.” As the past two decades have exposed new audiences to Warhol’s moving images, another facet to the artist has reappeared.

As the past two decades have exposed new audiences to Warhol’s moving images, another facet to the artist has reappeared.