|

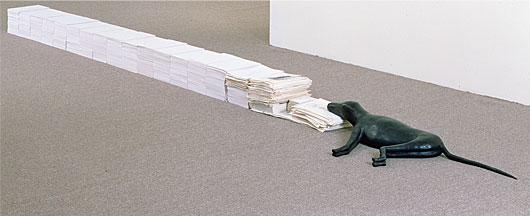

Dan Byers next to Drain, a sculpture by Robert Gober.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

|

|

Ordinary Madness

Dan Byers, Carnegie Museum of Art’s associate curator of contemporary art, wants visitors to embrace—even enjoy—the unease that contemporary art can inspire. So he’s pulled works from the museum’s vast collection to create an exhibition that speaks to something everyone can relate to: the insanity of everyday life.

By Cristina Rouvalis

Dan Byers has watched museum-goers smirk, roll their eyes, even swear at contemporary artwork, as though they were on the receiving end of a cruel hoax. “It’s incredible that an inanimate object can illicit such strong emotions,” says Byers, associate curator of contemporary art at Carnegie Museum of Art. “The same person would just change the radio station if they didn’t like a song.”

But instead of a smug inside joke, explains Byers, contemporary art can provide a powerful tool for people to confront the universal experiences and startling contradictions of daily life. In fact, that’s the theme of Byers’ upcoming exhibition Ordinary Madness, one of only a few contemporary group exhibitions to be staged in the Heinz Galleries other than the Carnegie International and the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh’s Annual in more than 30 years. (A members-only preview is slated for October 14.)

A shower drain, doll clothing, and a man in a Yoda mask are among the everyday objects and images that will be on view. But in this exhibition, the everyday turns playful and unsettling, beautiful and bizarre.

“On the one hand, I would say make contemporary art more accessible,” Byers says. “But on the other hand, I want people to be comfortable with the feeling of uncomfortableness.”

Consider the work I Don’t Like Mondays, the Boomtown Rats, Shooting Spree, or Schoolyard Massacre by artist Karen Kilimnik. It’s a response to the events of January 29, 1979, the day 16-year-old Brenda Ann Spencer fired a semi-automatic rifle on an elementary schoolyard across from her San Diego home, killing the principal and janitor and wounding a police officer and many children. When asked why she did it, she told a reporter, “I don’t like Mondays,” a chilling statement immortalized in a song by the Irish punk band The Boomtown Rats.

More than a decade later, in 1991, Kilimnik unveiled her installation of shooting targets, chicken wire, a Wiffle ball and bat, a jump rope, a lunchbox, a mechanical toy dog, and photocopies of newspaper coverage seemingly strewn about at 303 Gallery in New York. Fake blood and bullet-like holes penetrated the pristine white gallery walls. Byers describes the installation as “a shooting range, magazine spread, classroom, child’s bedroom, and crime scene.”

The well-received work hasn’t lost its poignancy, especially after subsequent shootings at Columbine, Virginia Tech, and dozens of other schools. This past December, Byers made the work his first purchase for the museum because he thought it was an important early example of “scatter art” from the late 1980s and early 1990s when artists were using everyday materials and images from popular culture in poignant, sometimes abject installations. He was also moved by its themes.

“It's not just the violence,” says Byers. “Or a journalistic response. The work is made from many connotations of the event: the voyeurism of a 24-hour news culture that fascinates on the abject; the response of a punk band in another country; the atmosphere surrounding the action. Finally, you have the materiality of the installation, which becomes a kind of metaphor for the experience of being affected by the culture around you. It’s a harrowing subject filtered through the artist’s highly personal, removed position—a response that goes beyond reportage into an aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.” “It's not just the violence,” says Byers. “Or a journalistic response. The work is made from many connotations of the event: the voyeurism of a 24-hour news culture that fascinates on the abject; the response of a punk band in another country; the atmosphere surrounding the action. Finally, you have the materiality of the installation, which becomes a kind of metaphor for the experience of being affected by the culture around you. It’s a harrowing subject filtered through the artist’s highly personal, removed position—a response that goes beyond reportage into an aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.”

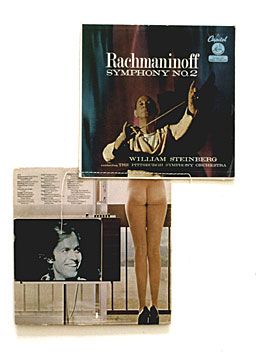

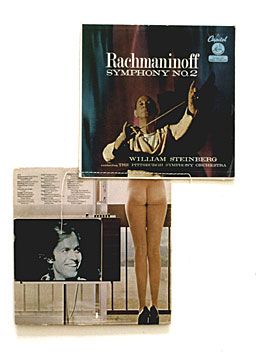

Christian Marclay, Symphony No. 2, 1991, Mr. and Mrs. James H. Rich Fund © Christian Marclay.

By permission. Photo: Paula Cooper Gallery

The tragic and the divine

Acquiring art about such a disturbing event is always carefully considered, and not just by Byers and his fellow curators. Museum board members, who approve all acquisitions, participated in a lively debate before signing off on the Kilimnik piece, with one member concerned that it would be too upsetting for young viewers.

“I would rather have a discussion about school violence happen around pieces of scattered cardboard in an art museum than around Fox News,” notes Byers. “The materials in this exhibition are far less damaging than anything you would see on TV or the Internet. It’s abstract. It’s not explicit. And, most importantly, it is an artwork—a proposition for thinking and looking at the world in a different way, that joins music, movies, and literature as a force to clarify and complicate our world. The buildup is a lot scarier than the work itself.”

Other works that will be seen in Ordinary Madness are playful, including a 1991 collage by visual artist and DJ Christian Marclay, who through his musical experiments helped pave the way for today’s popular turntable “mixing.” As part of his series Body Mixes, Marclay sewed together a pair of incongruous record album sleeves to create a new image: the face of dignified conductor William Strinberg seemingly attached to the bare legs and posterior of a seductive woman. “It’s like an exquisite corpse,” says Byers. “It’s creating a humorous collage and, at the same time, engaging our penchant towards mash-up culture.”

All of the 120 works in the exhibition were mined from the museum’s far-reaching contemporary collection, some displayed during previous Carnegie Internationals, and

others to be shown for the first time. Seen through the fresh eyes of 29-year-old Byers, the work is organized in an original, “quirky” fashion, as he describes it, not chronologically as often is the case. The idea, he says, is to provide new perspectives by pairing work that normally would not be viewed together.

On one wall, for example, visitors can compare two quite different paintings of masculinity from the early 1970s. Alex Katz’s grinning self-portrait exudes so much all-American self-confidence that it looks like it was plucked from the TV drama Mad Men. Next to it is a David Hockney portrait of Divine, the transvestite and cultural icon best known from John Waters’ film Pink Flamingos, stripped of his female wig and all illusion.

Karen Kilimnik, I Don't Like Mondays, the Boomtown Rats, Shooting Spree, or Schoolyard Massacre, 1991, A. W. Mellon Acquisition Endowment Fund © Karen Kilimnik. By permission. Photo: 303 Gallery

Revisiting history—quirks and all

Byers joined the Museum of Art’s curatorial team last summer, having arrived in Pittsburgh from the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, where he was the curatorial fellow in the department of visual arts. Before that, he was assistant to the directors at The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. When he accepted the Carnegie Museum job, the contemporary art department and the museum itself were, in a way, in a transition—Douglas Fogle, the department’s curator and orchestrator of the 2008 Carnegie International, had left for the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and no one had yet been hired to replace former longtime museum director Richard Armstrong.

It seems Byers’ timing couldn’t have been better. Lynn Zelevansky, the former curator of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was soon named the museum’s Henry J. Heinz II Director, and under her leadership, there’s a heightened emphasis on contemporary art outside of the Carnegie International, which is staged every three to five years. It seems Byers’ timing couldn’t have been better. Lynn Zelevansky, the former curator of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was soon named the museum’s Henry J. Heinz II Director, and under her leadership, there’s a heightened emphasis on contemporary art outside of the Carnegie International, which is staged every three to five years.

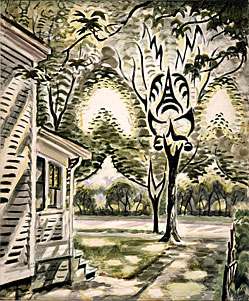

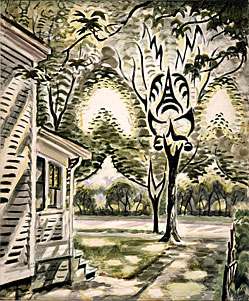

Charles E. Burchfield, Sun Glitter, 1945, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James H. Beal. Reproduced with permission from the Charles E. Burchfield Foundation

“We were the first contemporary art museum in the country,” says Zelevansky. “We have an amazing collection of art from 1985 to the present. We don’t have enough of it out enough of the time.”

Not that he needed it, but this directive gave Byers extra incentive to scour the museum’s vast contemporary art collection. At the heart of Ordinary Madness are its strengths, quirks, and even a taste of its storied history. Not that he needed it, but this directive gave Byers extra incentive to scour the museum’s vast contemporary art collection. At the heart of Ordinary Madness are its strengths, quirks, and even a taste of its storied history.

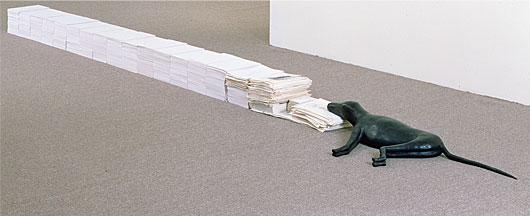

Barry Le Va, On Corner - On Edge - On Center Shatter (Within the Series of Layered Pattern Acts), 1968-1971, Carnegie Mellon Art Gallery Fund © 2007 Barry Le Va. Courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery, New York. Photo: Tom LIttle

“The collection is very strong and reflective of the most important work being made since the early 1980s,” says Byers. He notes that, with some important exceptions like the museum’s film collection, the Museum of Art didn’t heavily collect the works of artists from the major American art movements of the 1960s and ’70s—Minimalism, Conceptualism, Post-Minimalism, and Pop—at the time of their production. Curators of past Carnegie Internationals, who have rotated about every four years, have since acquired work to fill in the gaps.

“On the one hand, I would say make contemporary art more accessible. But on the other hand, I want people to be comfortable with the feeling of uncomfortableness.”

- Dan Byers, associate curator of contemporary art

Pulling you in

One of Byers’ favorite finds while searching the museum’s collection is an installation by Post-Minimalist giant Barry Le Va, purchased by the museum in 2005. Formed from 20 pieces of plate glass stacked and then shattered by a sledgehammer, On Corner – On Edge – On Center Shatter (Within the Series of Layered Pattern Acts) is a glistening pit of crystals that’s part of an ongoing series the artist started in 1968. The large sheets of glass are familiar objects that have been abstractly distorted.

“What I would like to suggest is that in every work of art, no matter how strange it is, there is some object or material or process of making it that is familiar to the viewer,” says Byers. “People often don’t trust their understanding of objects. It is an incredibly beautiful and an incredibly violent and dysfunctional piece.”

Byers was especially thrilled to come across the work, not only because it makes a great addition to the exhibition, but because it played a crucial role in his development as a young curator. Byers was especially thrilled to come across the work, not only because it makes a great addition to the exhibition, but because it played a crucial role in his development as a young curator.

Ken Price, Mr. Icky, 2000, Helen Johnston Acquisition Fund © 2000 Ken Price. By permission.

In 2008, Byers was a graduate student at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College in New York. As part of his final exhibition thesis, he was given just $2,500 to produce a group exhibition. The measly budget didn’t stop him from thinking big. He came up with the idea of pairing Le Va’s work with that of three other artists. Never mind that Byers was an unknown student curator. By way of his gallery, he sent Le Va, a major figure in the Minimalist and Post-Minimalist movements, a long letter outlining his idea.

About a month later, Le Va himself called Byers (who, by the way, let the call go into voicemail when he didn’t recognize the New York number). A couple days later, Byers sold Le Va on his idea. But then he was forced to come clean about his budget.

Top: Mark Manders, Several Drawings on Top of Each Other, 1990-2002, Gift of The Buddy Taub Foundation © 1990 Mark Manders. By permission.

Byers asked Le Va to make one of his well-known sculptures 30 percent smaller than their typical size.

“What kind of exhibition is this?” Byers recalls Le Va asking. The artist was accustomed to participating in well-funded exhibitions at major museums. “Ideally this is not how you would like to be dealing with an artist of this stature,” Byers admits. “But I really wanted the piece.”

Turns out, Le Va liked the smaller size in relation to the gallery’s architecture, and was supportive in helping Byers pull off his ambitious exhibition, which paired Le Va’s work with that of Los Angeles-based artist Charles Ray, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (featured in the 1999 International), and Rodney Graham. Perhaps most importantly, Byers learned an important lesson in resourcefulness that still applies today. Turns out, Le Va liked the smaller size in relation to the gallery’s architecture, and was supportive in helping Byers pull off his ambitious exhibition, which paired Le Va’s work with that of Los Angeles-based artist Charles Ray, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (featured in the 1999 International), and Rodney Graham. Perhaps most importantly, Byers learned an important lesson in resourcefulness that still applies today.

“You can’t expect to ship everything from, say, Hong Kong and South America,” he explains. “We’re in a recession.”

Despite his youth, that’s experience talking. Byers has been curating exhibitions for a decade, his first as an undergraduate at Skidmore College. He started as an art major, hoping to become a painter. But his sophomore year, Byers landed a work-study internship at the school’s Tang Museum, and his mentor there, curator Ian Berry, took him under his wing. He was 19 and never looked back.

“A lot of curators are former or failed artists,” says Byers. “I don’t consider myself a failed artist. I never really tried. To be an artist, you have to know 200 percent that this is what you want to do. I am a much more social person. I like working with artists, mediating their work, and bringing it to the public.”

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. XI, 1977/2004, Nancy and Milton Washington Fund

© Senga Nengudi. By permission. Photo: Tom Little

Art informing life

Within months of joining the museum, Byers decided he wanted to reach out more directly to the Pittsburgh community, and he and his colleagues have begun doing exactly that through Culture Club, a program that combines cocktails and art conversation at the museum every third Thursday of the month. It’s a way, Byers says, to help people mix art into their lives on a more regular basis.

After all, his inspiration for Ordinary Madness comes from one of his favorite books of poetry, Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara. A curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the 1940s and ’50s, O’Hara would jot down poems over lunch. “I love the idea that he was working with art and then he would go into the world and let the city spur on these poems, and art would be in the background,” says Byers.

“What I would like to suggest is that in every work of art, no matter how strange it is, there is some object or material or process of making it that is familiar to the viewer. People often don’t trust their understanding of objects.”

- Dan Byers

“People used to pop into a museum for 20 minutes during a lunch break. Now it’s a day trip and you are expected to go to the gift shop and cafe, which is fine. But if you have 20 minutes, come into the museum and look at art and everything looks different.”

That’s Byers’ point with Ordinary Madness. Step just inside the museum’s front door and you’re free to wander through Dan Graham’s 1991 Heart Pavilion, a mirrored glass sculpture that visitors might remember from the 1991 International. It distorts the relationship between the viewer and the object. “It’s a little trippy,” adds Byers.

The lowly shower drain also gets new meaning when it’s mounted onto a museum wall. In 1989, American sculptor Robert Gober constructed a cast pewter drain with a cross in the middle of it.

“The minute you stick a drain in the wall, it turns the whole room upside down,” Byers explains. “The drain is where things go that we don’t want; the waste. Here in the museum, it is repositioned to the wall, a place of privilege. You can also find a religious icon in it.”

That three-inch sculpture has changed the way Byers views the world.

“Every time you take a shower,” he says, “think of a tiny drain with enough power to shift your entire perspective.”

|

“It's not just the violence,” says Byers. “Or a journalistic response. The work is made from many connotations of the event: the voyeurism of a 24-hour news culture that fascinates on the abject; the response of a punk band in another country; the atmosphere surrounding the action. Finally, you have the materiality of the installation, which becomes a kind of metaphor for the experience of being affected by the culture around you. It’s a harrowing subject filtered through the artist’s highly personal, removed position—a response that goes beyond reportage into an aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.”

“It's not just the violence,” says Byers. “Or a journalistic response. The work is made from many connotations of the event: the voyeurism of a 24-hour news culture that fascinates on the abject; the response of a punk band in another country; the atmosphere surrounding the action. Finally, you have the materiality of the installation, which becomes a kind of metaphor for the experience of being affected by the culture around you. It’s a harrowing subject filtered through the artist’s highly personal, removed position—a response that goes beyond reportage into an aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.”

It seems Byers’ timing couldn’t have been better. Lynn Zelevansky, the former curator of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was soon named the museum’s Henry J. Heinz II Director, and under her leadership, there’s a heightened emphasis on contemporary art outside of the Carnegie International, which is staged every three to five years.

It seems Byers’ timing couldn’t have been better. Lynn Zelevansky, the former curator of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was soon named the museum’s Henry J. Heinz II Director, and under her leadership, there’s a heightened emphasis on contemporary art outside of the Carnegie International, which is staged every three to five years. Not that he needed it, but this directive gave Byers extra incentive to scour the museum’s vast contemporary art collection. At the heart of Ordinary Madness are its strengths, quirks, and even a taste of its storied history.

Not that he needed it, but this directive gave Byers extra incentive to scour the museum’s vast contemporary art collection. At the heart of Ordinary Madness are its strengths, quirks, and even a taste of its storied history. Byers was especially thrilled to come across the work, not only because it makes a great addition to the exhibition, but because it played a crucial role in his development as a young curator.

Byers was especially thrilled to come across the work, not only because it makes a great addition to the exhibition, but because it played a crucial role in his development as a young curator.

Turns out, Le Va liked the smaller size in relation to the gallery’s architecture, and was supportive in helping Byers pull off his ambitious exhibition, which paired Le Va’s work with that of Los Angeles-based artist Charles Ray, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (featured in the 1999 International), and Rodney Graham. Perhaps most importantly, Byers learned an important lesson in resourcefulness that still applies today.

Turns out, Le Va liked the smaller size in relation to the gallery’s architecture, and was supportive in helping Byers pull off his ambitious exhibition, which paired Le Va’s work with that of Los Angeles-based artist Charles Ray, Felix Gonzalez-Torres (featured in the 1999 International), and Rodney Graham. Perhaps most importantly, Byers learned an important lesson in resourcefulness that still applies today.