|

Opening the Book on André Kertész

The trailblazing photojournalist celebrated—and documented—the universal pleasure of reading, and 104 of his images will be on display this fall at Carnegie Museum of Art.

By John Altdorfer

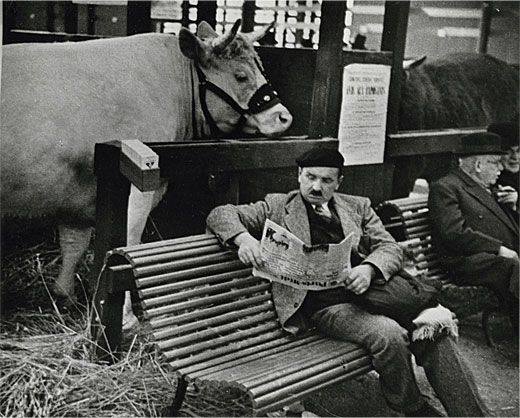

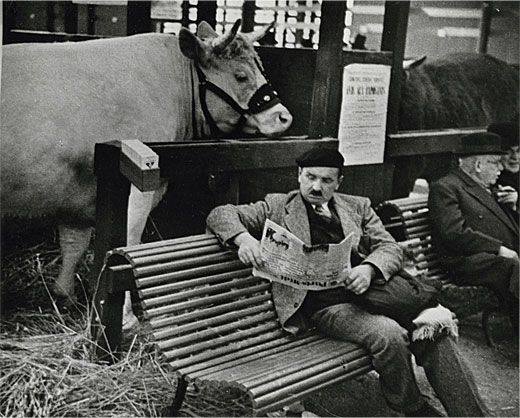

André Kertész, Paris, 1928 © Courtesy Estate of André Kertész/Higher Pictures 2007

Linda Benedict-Jones worries that the printed word is on the endangered species list. And for good reason. These days, many people are more likely to switch on their computers, Kindles, iPads, or cell phones than flip through the printed pages of a book or periodical, which is why the museum curator feels an urgency and sweet satisfaction in bringing André Kertész: On Reading to Carnegie Museum of Art.

Organized by the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College in Chicago, the exhibition opens October 23 and includes 104 images showcasing the work of the late Hungarian-born photographer André Kertész. For 50 years, Kertész more often than not focused his camera on people—from barefoot peasant boys to well-heeled society women—catching many in the deeply personal act of reading.

“Until a few years ago, this notion of reading from printed matter was commonplace,” says Benedict-Jones, Carnegie Museum of Art’s curator of photography and chair of exhibitions. “But today, looking at photographs of people reading things on paper is a kind of nostalgia.”

From his earliest days as a photographer, Kertész was fascinated with capturing people reading in the unlikeliest of places: backstage at a carnival, perched on the rooftop of an apartment building, or even stretched out beside a Venetian gondola. And his images are anything but ordinary. In a shot of a woman lost in the pages of a book while sitting on her rooftop, she’s beautifully framed by a tangle of vent pipes and fresh laundry flapping in the breeze.

For the most part, Kertész made these images in Hungary, Paris, and New York, the places where he spent significant portions of his life. But wherever he happened to be, the artist always kept an eye open for those special shots of people and their books or newspapers, celebrating the absorptive power and pleasure of this universal and solitary activity. He snapped some 200 readers over the course of his career, most blissfully unaware of being in the spotlight, instead appearing transported, fleetingly removed from life as we know it.

“In every photograph, there is a person reading, or an aspect of reading,” says Benedict-Jones. “There is also that delightful vision of André Kertész, and that is what is truly engaging for the viewers. At times his vision becomes a sort of journey that takes you around the frame. I think our audience will be rewarded for taking the time to see where the photographs lead them.”

On one such visual trek, a photograph of a cluttered New York City antique shop first draws the viewer’s attention to a large statue of a black minstrel on the left. Next to him is a young man seated near the center of the image, and then, a woman framed by a hoop-like object, comes into view in the background. All are reading, even the statue.

Though sometimes regarded as prickly in temperament, Kertész revealed a humorous side in many of his images. In one (above), a cow peers across the top of its holding pen over the shoulder of a man absorbed in a newspaper. Another shows a young boy in 1944 enjoying the “funny papers” on a New York City street as he perches on a messy stack of discarded newspapers destined for recycling as part of the World War II relief effort.

“Of course, the fact that Andrew Carnegie started this museum and a public library system that made it possible for people around the country to borrow and read books was a compelling reason to bring the show here,” notes Benedict-Jones, “But it’s also important because André Kertész is one of the most important and influential photographers of the 20th century.”

Among the first professional photographers to embrace 35mm cameras in the 1920s, Kertész captured his vision of the world as he roamed the streets of cities and countrysides across the globe. His work inspired, to name a few, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, and Brassaï to find that “decisive moment” and commit it to film. As Cartier-Bresson remarked, “Whatever we have done, Kertész did first.”

Kertész is perhaps best known for his groundbreaking contributions to photographic composition and for developing powerful photo essays. But early in his career, it was his then-unorthodox camera angles and unwillingness to compromise his personal photographic style that delayed recognition of his artistry.

While working at Polaroid in the early 1980s, Benedict-Jones met Kertész, just a few years before his death at the age of 91. She recalls the encounter as pleasant, though the aging photographer struggled to talk to her in a sometimes indecipherable mélange of Hungarian, French, and English. Whatever might have been lost in translation, he did sign a book of his work—André Kertész: Sixty Years of Photography—purchased by Benedict-Jones in the mid-1970s. That slight volume served as her introduction to his work, and led her to another of his books, On Reading.

Almost 30 years later, as Benedict-Jones prepares to introduce Kertész to a wider audience in Pittsburgh, she opens a copy of On Reading to the nearly century-old image of Hungarian youngsters in tattered clothes, seated on a mound of dirt in front of a wall, sharing what Kertész called a “universal pleasure.”

“For those three little boys, the act of reading was mesmerizing,” says Benedict-Jones. “This one image speaks so much about the importance of books and the importance of reading. That, and an appreciation for a unique way of seeing, is what I hope people take away from this exhibition.”

|

Fall 2010

Fall 2010